Wassily Kandinsky Syncs His Abstract Art to Mussorgsky’s Music in a Historic Bauhaus Theatre Production (1928)

European modernity may never had taken the direction it did without the significant influence of two Russian artists, Wassily Kandinsky and Modest Mussorgsky. Kandinsky may not have been the very first abstract painter, but in an important sense he deserves the title, given the impact that his series of early 20th century abstract paintings had on modern art as a whole. Inspired by Goethe’s Theory of Colors, he also published what might have been the first treatise specifically devoted to a theory of abstraction.

The composer Mussorgsky’s most famous work, Pictures at an Exhibition (listen here), had a tremendous influence on some of the most famous composers of the day when it debuted, which happened to be after its author’s death. Written in 1874 as a solo piano piece, it didn’t see publication until 1886, when it quickly became a virtuoso challenge for pianists and a popular choice for arrangements most notably by Maurice Ravel and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who, along with Igor Stravinsky and others, interpreted and expanded on many of Mussorgsky’s ideas into the early 20th century.

Mussorgsky’s early death in 1881 prevented any living collaboration between the painter and composer, but it’s only natural that his minimalist musical piece should have inspired Kandinsky’s only successful stage production. In Kandinsky’s theory, musical ideas operate like primary colors. His paintings explicitly illustrate sound. In his stage adaptation of Pictures at an Exhibition, he had the opportunity to paint sound in motion.

Kandinsky was first inspired to paint, at the age of 30, after hearing a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin. “I saw all my colors in spirit,” he remarked afterward, “Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.” The Denver Art Museum’s Renée Miller writes of Kandinsky’s experience as an example of synesthesia. He drew from the work of Arnold Schoenberg in his abstract expressionist canvases, and “gave many of his paintings musical titles, such as Composition and Improvisation.”

For his part, Mussorgsky found inspiration for his nonrepresentational work in the strangely uncanny representational visual art of Russian architect and painter Viktor Hartmann, his closest friend and member of a circle of artists attempting a nationalist Russian cultural revival. Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition sets music to a collection of Hartmann’s paintings and drawings exhibited after the artist’s death, including sketches of opera costumes and a monumental architectural design.

The creation of several highly distinctive musical motifs is of a piece with Mussorgsky’s opera compositions. Both he and Kandinsky were drawn to opera for its dramatic conjunction of visual art, performance, and music, or what Wagner called Gesamtkunstwerk, the “total work of art.” And yet, despite their mutual admiration for classical forms and traditional Russian folklore, both artists illustrated the title of Wagner’s essay on the subject, “The Artwork of the Future,” more fully than Wagner himself.

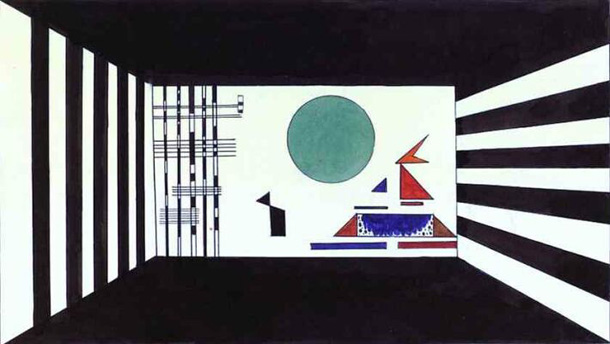

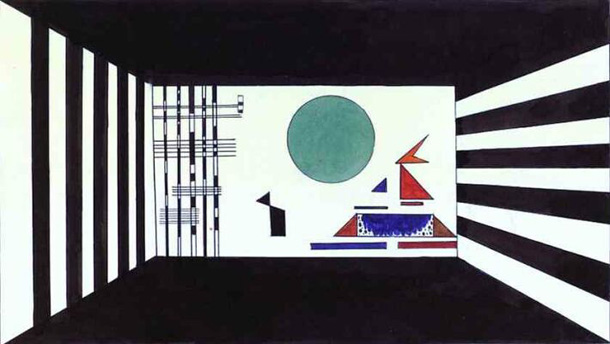

Mussorgsky’s piece, as composed solo on the piano, is willfully odd, ugly and piercingly beautiful by turns, and always unsettling, like the Hartmann paintings that inspired it. So visually descriptive is its musical language that it might be said to induce a virtual form of synesthesia. In illustrating Pictures at an Exhibition, Kandinsky “took another step towards translating the idea of ‘monumental art’ into life,” notes the site Modern Art Consulting, “with his own sets and light, color and geometrical shapes for characters.”

On April 4, 1928, the première at the Friedrich Theater, Dessau, was a tremendous success. The music was played on the piano. The production was rather cumbersome as the sets were supposed to move and the hall lighting was to change constantly in keeping with Kandinsky’s scrupulous instructions. According to one of them, “bottomless depths of black” against a black backdrop were to transform into violet, while dimmers (rheostats) were yet to be invented.

Rather than translating Mussorgsky’s piece back into Hartmann’s representational idiom, Kandinsky creates an operatic movement of geometrical figures from the lexicon of the Bauhaus school. (Only “The Great Gate of Kiev,” at the top, resembles the original painting.) Rather than create narrative, “Kandinsky’s task was to turn the music into paintings,” says Harald Wetzel, curator of a recent exhibit in Dessau featuring many of the set designs. Those static elements “give just a limited impression of the stage production,” which was “constantly in motion.”

We may not have film of that original production, but we do have a very good sense of what it might have looked like through its many re-stagings over the past few years, including the production further up with pianist Mikhaïl Rudy at the théâtre de Brive in 2011 and the animated video remake above, which brings it even further into the future. See a selection of photos from the Kandinsky exhibit at Deutsche Welle and compare these paintings with the original pictures by Viktor Hartmann that inspired Mussorgsky’s piece.