Music Is Ephemeral: That Makes It Difficult To Write About. Also To Understand How A Conductor Does What S/he Does

All the music-makers

Stephen Brown on the conductor and the challenges of putting sounds into words

Such stories reinforce one of Mark Wigglesworth’s points: that a conductor’s preparation of a work through score-study, listening and rehearsal is more important than the actual waving of the arms in performance. Or they may reveal another truth he stresses, that sometimes the players don’t need – or heed – those waving arms. That the anecdotes come from my meagre store and not from what, given Wigglesworth’s thirty years of experience, must be an almost limitless supply, indicates the degree to which he favours the general over the specific. An experience he does particularize is one, curiously, I share with him: he and I were both riveted by what I suspect was the same performance, a televised version of Mahler’s gigantic Eighth Symphony, from the early 1970s. If it was the same, Leonard Bernstein was the man on the podium, and it was wonderful. It made Wigglesworth want to be a conductor.

On the cover, the book is promoted as something directed at an audience member who needs to have the conductor’s role both justified and demystified. And to some extent the book does so, but often it seems more like Notes towards a Guiding Philosophy for the Aspiring Conductor. It is often addressed to “you” and that “you” does not seem to include all of us, but rather a young person contemplating a career. Such a person would surely be grateful for more on the brass tacks of a conductor’s life. Wigglesworth has valuable suggestions about dealing with musicians, but not much on the ancillary groups that I suspect take up an exasperating portion of a conductor’s working life: the orchestra’s administrators, musicians’ unions, symphony boards, patrons, to say nothing of the inevitable struggles over funding, whether public or private.

The score-study aspect of the conductor’s job is something which both the average concert goer and the aspiring young person should certainly be aware of. “The first time you look at a score, it is rather like reading a novel”, Wigglesworth says, as though it were that simple. If you were to look at an orchestral score at a moment when every instrument was playing a plain old B flat you would see an array of notations. The piccolo note will be written an octave lower than it sounds, the clarinets and trumpets a note higher than they sound, the French horn five notes higher. The violas are often in the tenor clef, so that the note is not on the third line but on the second space. Bassoons and cellos sometimes use the alto clef. And so on. To be able to translate these symbols into a coherent pattern so that they can be read in the rhythm of the music seems to me, as one incapable of so doing, an amazing feat.

I was surprised not to see more about bowing. Violinists don’t move their bows up and down in unison by accident. Someone – and it’s usually the conductor – goes through the score and marks every up-bow and down-bow. Arcangelo Corelli, at the very beginning of the orchestral tradition, insisted on uniform bowings (as I learned from Robert Philip’s book also under review), and I’m told that the New York Philharmonic saves on file the bowings marked by leaders like Bernstein and Boulez. This is not done for visual consistency alone. When I questioned a conductor friend he asked if my (tennis) forehand was the same as my backhand. Working with or against gravity changes the quality of the sound. A superb violin section will be able to sustain longer bowings than a student orchestra. And if you don’t indicate bowings for the cellists, players might cross swords with their stand-mates.

Wigglesworth is calm, intelligent, perspicacious, literate (although does anyone remember Noël Coward’s Mrs Worthington nowadays?), generally serious though sometimes wryly humorous, but … Well: “but”. I don’t believe I have ever read a book so burdened with that conjunction. Wigglesworth’s relentless even-handedness leads him into the realm of the anodyne. Here’s an example: “Humour can be a most valuable tool in creating and maintaining a positive atmosphere … But you have to be careful. Not everybody’s sense of humour is the same”. Another: “Researching the circumstance of a composer’s life can be invaluable in grasping the voice with which they speak, but it can also be limiting, or even positively unhelpful”. As Mr Coward would say, No more buts, Mr Wigglesworth.

I wish he had written more about the conductor’s relationship with soloists, surely often requiring delicate negotiation. One circumstance he may not have run into: my piano teacher Harold Zabrack was a bit of a prodigy, and got to perform Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto with the St Louis Symphony back in the early 1950s, when the conductor was Vladimir Golschmann, famous, among other things, for knowing how to fling his conducting arm up so that his gigantic diamond ring would flash in the spotlight. My teacher – as he told the story – walked out on stage to find Golschmann motioning him over to the conductor’s podium. “Now, Harold”, he said, putting his arm over Harold’s shoulder, “look as though we’re discussing some fine point in the score … and reach down and do up your zipper.”

Michael Innes’s classic detective novel Appleby’s End starts in a train carriage in which young Appleby is puzzled by a collection of books carried by one of his fellow travellers. It turns out that the man is single-handedly writing an encyclopedia, turning out volumes by the month for a supermarket. This is the scale of Robert Philip’s accomplishment: the book is one that you might have expected a team of experts to work on for years. It could put programme note-writers out of work. Or make their jobs easier, should their ethics allow, for, in effect, it supplies programme notes enough for thousands of concerts, since most orchestral concerts are based on the 400 works included. Although billed as a “companion”, at just under a thousand pages and weighing almost 4lbs, it is not one you’ll want to carry with you to a concert.

Writing about food is hard; writing about perfume must be even harder; but writing about music is difficult enough. Not only are musical patterns and effects hard to put into words, but because music flows in time, they are evanescent, never standing still long enough to be focused on – “in the air, and then it’s gone”, as Eric Dolphy said. One solution far too often relied on by programme note-writers is to fall back on technical description: “X’s use of a surprising sub-dominant chord to transition back to the minor key …”, which is exasperating enough for a musician, let alone the common listener who is supposed to learn something from it.

This is the easy way out (for the writer) that Philip avoids almost entirely, although he does fall into the trap from time to time (how is a non-musician to know that a modulation from G major to B major, as in Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto, is unexpected, while moving back and forth between G major and E minor, as in Fauré’s Pelléas suite, is barely noticeable?) What he does instead is walk us patiently through each work with a combination of travel guide and plot summary, noting landmark musical events while using evocative words to personify their effects. For example, for the first movement of Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto he runs through the adjectives “haunting”, “cheeky”, “insouciant”, “nervous”, “chattering”, “strutting”, “mocking”, “doleful” and “brilliant”. And in fact the piece is all those things.

Which brings me to what I like best about the book: that Philip is unafraid of voicing his opinions, and that the opinions are so often convincing. About Chopin: “There is as much variety and complexity in ten minutes of a Chopin Ballade for solo piano as in the forty minutes of Liszt’s ‘Dante’ Symphony for huge orchestra”. Debussy: “In traditional musical language before Debussy, time moves on inexorably, with the progression of harmonies pushing it forward like a stream. But with Debussy it is as if we have left the ground”. It was not by accident that Debussy twice based works – a song and then a piano prelude – on Baudelaire’s “Harmonie du soir”, where time is a flower trembling on its stem. The Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Berg, Webern) seems to him a brilliant but esoteric backwater. He finds in Mahler and Shostakovich a deeper understanding of the modernist aesthetic of juxtaposition, irony and pastiche. Which makes one consider the amazing feat of Shostakovich continuing to develop a modernist sensibility in a Stalinist environment. Mozart “seems like a man who understands every aspect of the human condition”. Comparing Mozart to Mendelssohn, he notes that Mendelssohn’s talent as a youth was equal to Mozart’s, but where Mozart’s career was a constant flux of change and development, the youthful Mendelssohn was also the mature Mendelssohn. I tried this out on some colleagues, who did not agree. But that’s the beauty of opinions – they give readers space for their own. There is an eat-your-vegetables quality in much purportedly educational writing about music, and nothing is less conducive to enjoying art than being told that you must. Even with universally admired masterworks, it is nice to be reminded how some contemporary critics dismissed them.

No one wants to be seen as a boring know-it-all, but who can deny the pleasure of having something knowledgeable to contribute to an intermission conversation? If I’m ever, God forbid, stuck at a concert that features Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory, I will now be able to point out that it was originally written for a mechanical orchestra, a “Panharmonicon” devised by Johann Mälzel of metronome fame. The music of Alexander Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy is justly famous; his poem of the same name less so. Philip quotes a fragment (translated by Hugh Macdonald, who probably improved it) that surely must be some of the worst poetry ever written: “The spirit / Pinioned on its thirst for life / Soars in flight / To heights of negation”. Scriabin was so pleased with these lines, he used them twice. Philip quotes Richard Strauss at an early rehearsal of Don Juan: “Fifty notes one way or the other won’t really make any difference”. A reassuring thought for every amateur pianist.

The biggest questions remain unanswered. Philip introduces us to the “dotted rhythm theme” and the “lyrical melody” of the Brahms Violin Concerto, but I am still waiting for someone to explain to me why the first sends a thrill down your spine and the second melts your heart.

I was disappointed that Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana was absent, and although I am not a huge Schoenberg fan, I do respect his Piano Concerto, also missing. I missed them mostly because I would like to hear what Philip says about them. An otherwise comprehensive index missed the Dvorák Cello Concerto. Which reminds me of Mark Wigglesworth’s odd statement that “Composers might often be dead, but at least the performers never are”. I couldn’t figure out what he meant by that sentence, since I was listening to Jacqueline du Pré playing the Dvorák as I read it, and she is definitely gone from us. Except that as long as we keep listening and playing and talking, they are all, all the music-makers, still alive.

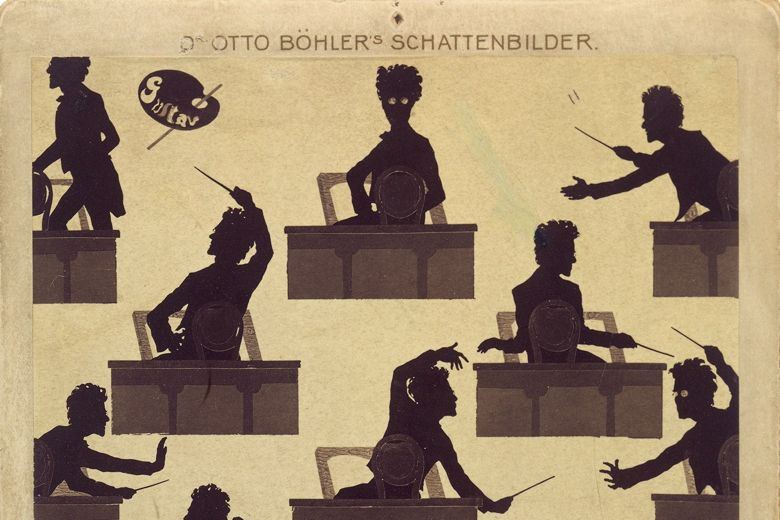

photo: Silhouettes of Gustav Mahler by Otto Böhler (1847–1913) © DeAgostini/SuperStock