How the classical took control of the jazz in ‘Rhapsody in Blue’

by Matthew Guerrieri

(Main photo: Robert Alda mimed playing the piano in the 1945 fictionalized George Gershwin screen biography “Rhapsody in Blue.”)

At the center of “Rhapsody in Blue” — the dramatically banal but musically rich 1945 film biography of George Gershwin — is a re-creation of the title work’s 1924 premiere. Bandleader Paul Whiteman, playing himself, conducts. Pianist Oscar Levant, playing himself, watches from the audience. And Robert Alda, as George Gershwin, tries to look like he’s playing the piano.

Actually, he’s pretty good. It’s Levant on the soundtrack, but Alda (coached by Ray Turner, a Whiteman band alumnus turned studio pianist) does better-than-average pantomime. For one series of upward cascades, each finished with a chord, Alda’s fingers are conveniently hidden, but he convincingly mimics the flow of the arms, the body’s turn, the weight of accents. Only the reflection off the well-polished piano lid gives away the game: Alda hardly even touches the keys.

But there are moments featuring Alda and the keyboard in the same frame, and his playing seems to be spot-on, the right keys in the right rhythm. And yet his body lacks ease and grace; he sits ramrod straight, frozen, only gingerly turning his head now and then. Close viewing reveals a special effect: a double exposure, Alda’s head superimposed on Turner’s body, the illusion requiring both performers to remain absolutely, unnaturally still. The most precise pianism of the sequence is also the most stiff.

The effect unwittingly captured the work’s inherent conflict: between accuracy and freedom. It’s a dilemma common to most of the classical repertoire; but in “Rhapsody in Blue,” the deliberations have been especially long, and twisty —because the accuracy and freedom easily brought to mind other categories: classical and jazz.

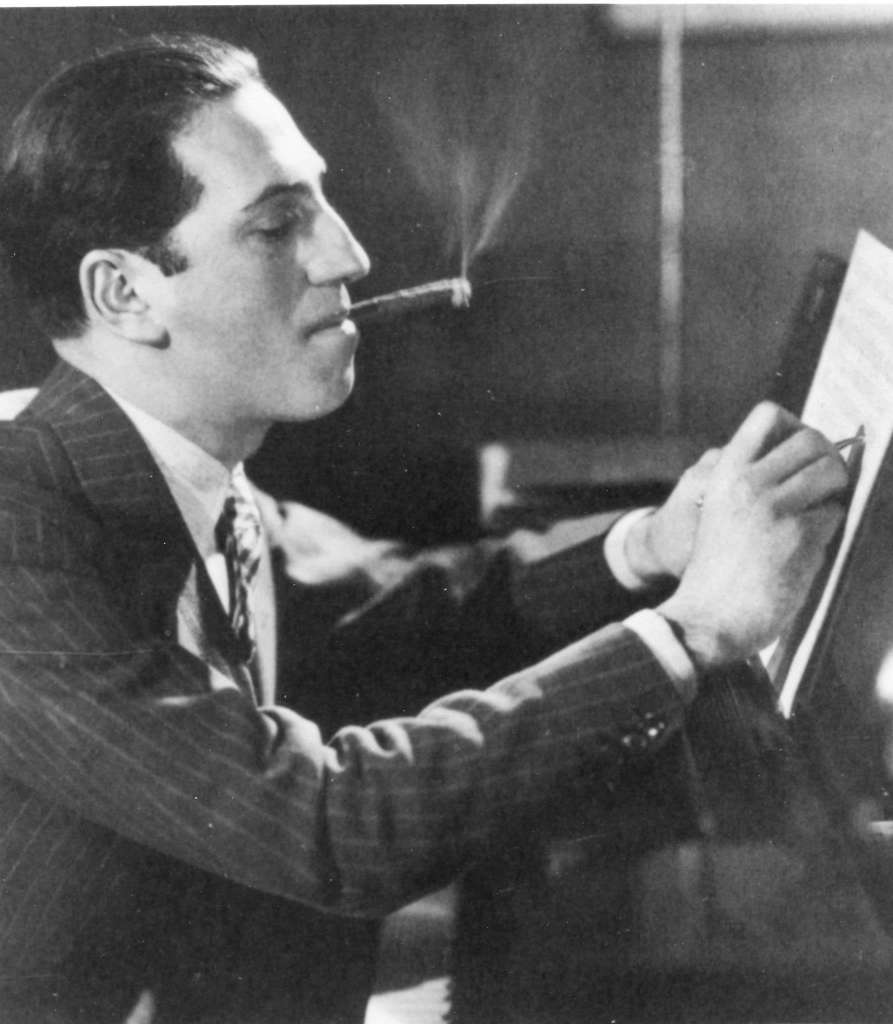

George Gershwin.

Take the grandest of the work’s famous tunes, the lyrical E-major Andante. On paper, it’s constructed along popular-song lines: two bars of sweeping melody answered by six bars of harmonic murmuring, a tread of eight-bar phrases. Listen to early recordings of the “Rhapsody” — including Gershwin and Whiteman’s 1924 acoustic recording — and you’ll hear the gentle, steady procession of those two-plus-six-bar groups. Today, however, you’ll almost never hear that rhythm. For decades, the more common practice has been to play those six-bar consequents twice as fast. The results are, in essence, odd, asymmetrical five-bar phrases rather than the eight-bar Broadway standard.

The piece has, in this instance, tipped away from dance-band steadiness toward Romantic, concert-hall rhetoric. (Even Gershwin adopted the double-time interpretation in later performances.) A tempo at which all eight bars can be played without the music getting bogged down leaves insufficient room for a virtuoso to bring out the Brahmsian yearning in the first two bars. A bit of the work’s notated, Tin Pan Alley DNA, its pop-song symmetry, has been sacrificed at the altar of classical expression.

In 1957, jazz pianist and arranger Calvin Jackson released an album of “Jazz Variations on the Rhapsody in Blue,” giving the “Rhapsody” an up-to-date big-band treatment: the 3+3+2 clave rhythm of the Agitato pumped full of Latin-jazz horsepower, and so forth. Reportedly, Ira Gershwin, George’s brother, lyricist, and posthumous guardian, found Jackson’s arrangement disrespectful and tried to suppress the album. As the “Rhapsody” solidified its place in the canon, the freedoms of jazz — to rework, rearrange, improvise — came into growing conflict with the work’s status as a fixed masterpiece. (Interestingly, Duke Ellington’s 1963 version brought no similar objection, perhaps because Billy Strayhorn’s arrangement was more nostalgic homage than in-vogue upgrade.)

At the same time, classical freedoms — to emphasize notes, to shape phrases, to stretch rhythms — were applied in ever-greater profusion to the work. The “Rhapsody” was published in a variety of forms (solo piano, piano duo, piano-and-orchestra), all diverging from each other in ways large and small. Such flexibility, standard in vaudeville and theater, became, in the concert hall, a vacuum to be filled. For his influential 1959 recording with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein famously edited the orchestral version to match the solo piano version, not only cutting 60 bars, but giving the whole a soloist’s rhythmic cast: every theme unfolding in an undulating rubato, every expressive turn lingered over, every tempo a portal to further deliberation.

In addition, Ferde Grofé’s symphonic orchestration held sway for decades, further suffusing the “Rhapsody” with a classical aura. It wasn’t until the 1970s that Grofé’s original jazz-band arrangement, the one heard at the 1924 premiere, was revived. Michael Tilson Thomas even conducted a recording in which the Columbia Jazz Band played along with Gershwin himself, via piano roll. Was it a reassertion of the work’s jazz roots? Or was another classical-music faction, the early music movement, the domain of historically informed practice, expanding its territory? It seemed to spark another reaction: Beginning with Marcus Roberts’ 1995 trio-with-orchestra reinvention, jazz musicians reapproached the “Rhapsody” with increasing boldness.

Pianist Oscar Levant, pictured in 1951, did the actual playing in the “Rhapsody in Blue” movie, and played himself in the film.

When the “Rhapsody” bowed, classical was seemly, jazz the outsider. By the time the jazz-band version was again in the ascendant, jazz itself had become “America’s classical music.” Now, both traditions are marginal to popular-music dominance. Near the end of the 1996 Ben Folds Five single “Underground” — a cheery, piano-pop ode to more hard-core musical subcultures — Folds, at the piano, drops in a quote from “Rhapsody in Blue.” Even the most daring cross-stylistic experiment eventually occupies just another niche. Nevertheless, the work’s competing forces still jostle for space. To perform the “Rhapsody” is, in part, an exercise in diplomacy.

Back in 1927, the American abstract painter Arthur Dove, needing inspiration, had his wife pick up a stack of 78s, including the Whiteman/Gershwin “Rhapsody.” To one of his painted responses, Dove added a sculptural element: a watch spring, attached to the top of the canvas, the metal ribbon spooling down in a vague but persistent spiral. The dance-band timekeeping in “Rhapsody in Blue” can be spun out into the classical realm; but stretched too far, it’s liable to recoil.

Matthew Guerrieri is a writer and musician living in Massachusetts.