Feed your soul: the 31-day classical music diet

From gentle awakening to explosive fanfare, duelling pianos to one chill lone voice, expand your horizons with a month’s worth of classical ear-openers

For Observer readers, January’s cultural diet is now a habit: first literature, in 2020, then last year’s sequel, short films. The best way to engage with those, surely, was sitting down with a box of chocolates and a hot-water bottle. Here’s a diet where you can listen and walk the dog, lift dumbbells, practise hula or, with care, reverse running. Whatever fitness trend you may have signed up to in a fit of optimism can also, in theory, be done with headphones on.

You can also do nothing but be an active listener: follow the rhythms, instruments, textures, melodies, patterns as they unfold or repeat or turn themselves upside down. Classical music has a reputation for being dusty and difficult, something you have to know about to “get”. (Do you like it or not? Not such a hard question and the only one that matters.) These 31 pieces might lead you to aural pleasures as well as greater confidence in following your enthusiasms.

Choices have been shaped, in part, by the cold, dank days and long nights of January. A summer regime would have been altogether more airy. Away from live encounters in the concert hall, my preference tends to be contemplative and often quiet: a measure of what level of noise I want coming in through my headphones and invading rather than enhancing my day’s activities. You may have a different appetite for musical jolts and thumps and pulsating rhythms. All the composers here can provide that option too, easy to find with a bit of YouTube-ing or Googling. The boundaries of classical music are ever more porous and open, spilling into other forms and all to the good. Give up prejudice or fear or indifference. Open your ears. Get listening. Happy new year!

1

Sleepily

György Kurtág

(1979; 1 min 18 seconds)

Whether you wake up clear-headed or nursing a hangover, this drowsy piece will treat you gently. It’s from Játékok (Hungarian for “games”), a collection by the composer-pianist György Kurtág inspired by children’s play. He had his own way of writing down music and wanted the player to use palms, fist and forearms as well as fingers. The tickling clicks, swoops and sleepy yawns provide a short, somnolent start to the new year.

2

Holberg Suite, Op 40: Prelude

Edvard Grieg

(1884; 2 mins 36 sec)

Cling on to this last day of holiday before the general return to work. Time to act on those resolutions. Running maybe? Or maybe just rolling off the sofa. This blithe, galloping piece from a dance suite by Norwegian composer Grieg conjures open landscapes and a spirit of adventure. Too feelgood? The next choice is for you…

3

Nautilus

Anna Meredith

(2013; 5 mins 31 sec)

Accepting that many people had to work right through Christmas, for most of us reality beckons today. Nautilus, the noisiest piece on offer here, launches with an urgent horn fanfare then thuds its way into your consciousness. Its lurching, head-banging intensity may mirror the stress of your first commute of 2023. It’s a great, explosive piece by a composer of the moment.

Anna Meredith. Photograph: Gem Harris

4

Impromptu No 3 in G flat major, D899

Franz Schubert

(1827; 6 mins 20 sec)

Assuming “normality” day two will be harder than day one, today’s choice is Schubert. If this speaks to you, try the piano sonatas, especially the late ones, the symphonies, or any – yes, any – of the 600 songs. The song cycle Winterreise captures every aspect of hope and wintry sorrow. A universe of tenderness awaits.

5

Nagoya Marimbas

Steve Reich

(1994; 4 mins 55 sec)

Taking its name from the Japanese port city, this piece – mallets on wood – is an aural palate cleanser. Reich, a pioneer American minimalist of restless invention, says this 1994 version is similar to pieces he wrote decades earlier but with a difference: this is far harder and needs two virtuoso players. Patterns repeat and slip out of phase in Reich’s mesmerising universe of sound.

6

Clair de lune

Gabriel Fauré

(1887; 3 mins 4 sec)

For the first full moon of 2023, the orbed choice is Fauré’s Clair de lune, an ethereal setting of words by the poet Paul Verlaine from his collection Fêtes galantes (also set by Debussy). The voice creeps in long after the rippling piano. Think of the gardens and statues of Versailles, ghostly by moonlight. French song, or mélodie, comes no better.

7

Hymn of the Cherubim

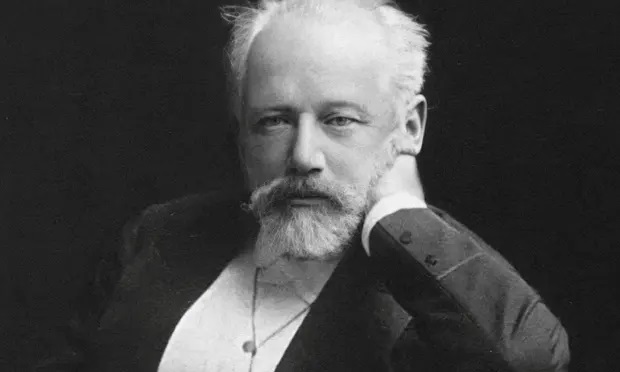

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

(1878; 7 mins 51 sec)

From Egypt to Serbia, Ethiopia to Ukraine, the Orthodox church celebrates Christmas today. Tchaikovsky’s meditative hymn is from his Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, first performed in Kyiv in 1879. The imperial church had a monopoly over music for the liturgy. Tchaikovsky found himself embroiled in a political storm: censored for writing one of the most radiant settings you could ever find.

Tchaikovsky. Photograph: Last.fm

8

Dances in the Canebrakes

Florence Price

(1953; 2 mins 35 sec)

Get dancing. Canebrakes (thickets of cane found in the marshy lands of the deep south) had to be cleared for cultivating cotton – hard labour for enslaved Black people. This is one of the last works by Price, originally for piano but orchestrated by her fellow Black American composer William Grant Still. Hear the influence of ragtime rhythms in these three joyful pieces and shimmy along.

9

String Quartet II: Assez vif – très rythmé

Maurice Ravel

(1903; 6 mins 29 sec)

Every piece by Ravel is jewelled and singular. Born in the French Basque region, described by one observer as looking like a well-dressed jockey, he was a perfectionist, his output small, each work a masterpiece. He wrote one string quartet. The first section of this movement is played pizzicato (plucked, rather than bowed). The effect is magical, buoyant, bubbling. Then suddenly it changes direction.

10

Partita in C minor BWV 997, Prelude

JS Bach

(1738-41; 3 mins 6 sec)

The temptation to devote the entire month to Bach proved nearly irresistible. But this is a diet with restriction and exclusion implied. So feast on this lute partita, exquisitely played, in the playlist choice, on guitar. Then follow your instinct and if you encounter other Bachs on the way – CPE, two varieties of JC and more – try it all.

11

Plan & Elevation: V. The Beech Tree

Caroline Shaw

(2019; 2 mins 36 sec)

Springing from a fascination with architectural drawings, space and proportion, the American composer Caroline Shaw’s Plan & Elevation for string quartet includes movements called The Cutting Garden, The Herbaceous Border and The Orangery. Shaw says The Beech Tree is her “favourite spot in the garden”, for which the music is simple, ancient, elegant, quiet. One of her inspirations is Ravel. Compare and contrast.

Caroline Shaw. Photograph: Dayna Szyndrowski

12

Oblivion

Astor Piazzolla

(1982; 3 mins 34 sec)

There’s no escaping melancholy in the music of Piazzolla, the Argentinian tango composer and bandoneon player. Is this jazz or classical, for smoky night club or concert hall? It’s for all. He studied classical composition in Paris – check out his teacher, Nadia Boulanger – and took his knowledge home, writing an estimated 3,000 pieces and making the classical world tear down its narrow boundaries.

13

Symphony No 5 (opening)

Gustav Mahler

(1902; 3 mins 19 sec)

Tár, starring Cate Blanchett as a conductor, is released in the UK today. The film’s trailer asks: “Do you ever find yourself overwhelmed by emotion?” Never mind the question’s banality. The answer is certainly “yes” if listening to Mahler’s Symphony No 5, featured in the film. Epic orchestral works are excluded in this diet, but Tár’s soundtrack gives you a taster of this (emotionally overwhelming…) major composer.

Cate Blanchett in Tár. Alamy

14

Le Badinage, IV.87

Marin Marais

(1717; 3 mins, 55 sec)

Marais was a viol player at the court of Versailles who wrote music of descriptive strangeness. We’ll keep his The Bladder-Stone Operation for a different dietary occasion. His name came to the fore after he featured in the film Tous les matins du monde (1991), when he was played by Gérard Depardieu. Marais’s music – intimate, deep, pensive – goes round in your head for days.

15

Ave verum corpus

William Byrd

(1605; 4 mins 25 sec)

Byrd, who perilously kept his Catholic faith hidden in Protestant England, was a contemporary of Shakespeare. 2023 is the 400th anniversary of his death. Serene, soaring, unworldly, there will be plenty of Byrd around this year. As well as sacred music he wrote keyboard works and madrigals, leading the way in a golden age for composers of the first Elizabethan era.

16

Candide Overture

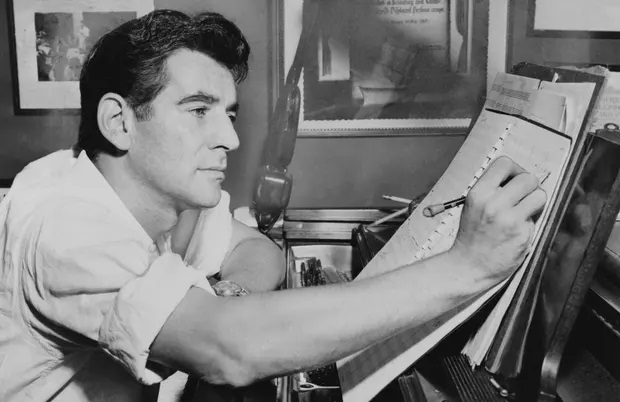

Leonard Bernstein

(1956; 4 mins 30 sec)

Let’s lift the mood for Blue Monday, nominated the most depressing day of the year: bad weather, the bills have arrived. We’re smashing the diet with an orchestral showpiece: Bernstein’s crazily catchy overture to Candide, from his operetta based on Voltaire’s novella. To mix up the work’s philosophy of optimism, and its famous songs, cultivate your garden, and glitter and be gay!

Leonard Bernstein in 1955. Alamy

17

The Song of the Sea

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou

(1953; 9 mins 33 sec)

This Ethiopian nun (b.1923), once a singer to Haile Selassie, imprisoned when her country was under Italian rule, has acquired cult status; once on the margins of classical music but now moving into mainstream consciousness. The Song of the Sea merges gentle arpeggios with a wash of rising chords and a plaintive song waving and weaving through all.

18

Giustino: Act 1: Vedrò con mio diletto

Antonio Vivaldi

(1724; 5 mins 13 sec)

The popularity of Vivaldi – usually topping the “most played” classical lists thanks to The Four Seasons – risks obscuring the glory of his expansive genius. The Venetian priest-violinist wrote church music, more than 500 concertos and 50 operas. He died in poverty. Try the exuberant Gloria or the haunting Stabat Mater. But start with this ravishing love aria from his opera Giustino.

19

Bagatelle Op 33, No 5

Ludwig van Beethoven

(1801-2; 3 mins 14 sec)

Beethoven needs no help. Anything of his is worth exploration. Here’s a piece that celebrates his humour (countering his reputation as a grouch). This tiny bagatelle – French for trifle – from one of the three sets (plus a few stray ones) he wrote across his lifetime, shows his capacity for surprise and wit. Hands race up and down the keyboard, jumping and skittering: a masterpiece in miniature.

20

O viridissima virga

Hildegard of Bingen

(12th century; 3 mins 49 sec)

Slow down and stop for this one: a solo voice in salutation to the Virgin Mary. The rich text celebrates the freshest green (viridissima) of nature: blossom and boughs, spices, grass and birds. Hildegard, a German nun of multiple talents, is one of the earliest named composers. Some performers prefer to sing her chants in groups, or accompanied by a drone, but the solo voice has an unmatched purity.

Hugo Wolf. Alamy

21

Italian Serenade in G major

Hugo Wolf

(1887; 7 mins 9 sec)

Full of delicious, jaunty melodies, this Italian Serenade darts off into dark, experimental corners, then snaps back into the sunlight. The Austrian composer, best known for his 300 songs, wrote this breezy string quartet late in life. His own charming personality was often thwarted by depression, which interfered with his creative work. This gem bursts with musical wit.

22

Cello Sonata in G minor: Andante

Sergei Rachmaninov

(1901; 5 mins 50 sec)

Today we mark two events of 2023: for China’s lunar new year, the choice is the international piano star Yuja Wang, born in Beijing. This is also the anniversary of the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943). In this slow movement from his Cello Sonata, the piano introduces a long, heart-rending melody, before cello and piano interact as equal partners.

23

Che si può fare

Barbara Strozzi

(1664; 9 mins 28 sec)

Strozzi moved in intellectual circles in baroque Venice, a celebrated virtuoso musician, but womanhood, her own illegitimacy and that of her children, plus her reputation as a courtesan, all conspired against her. This lament, with rapturous lute accompaniment, asks what can be done, what said, in the face of disaster. The question tugs, over and over, at the heart.

24

Sonata for Two Pianos in D major, K448: Allegro

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

(1781; 8 mins 31 sec)

Mozart, with Bach, Beethoven, Schubert (and more – don’t write in) is at the centre of western classical music. Mozart loved riddles, wordplay, card games, billiards. The two players, on two pianos, share the opening, bold statement then joyfully interweave and alternate, as if playing chasing games with each other. After this exhilarating opening, move on to the heavenly slow movement. Then the concertos, symphonies, operas, songs…

25

What power art thou (Cold Song)

Henry Purcell

(1691; 4 mins 26 sec)

One of the oddest and most inventive pieces Purcell wrote in his short, brilliant life is this aria from the frost scene in his semi-operatic spectacular King Arthur, to words by Dryden. Strings shiver and shake before the voice, still with cold, enters. Purcell himself died of a chill at the age of 36, supposedly after his wife locked him out. Others say it was chocolate poisoning.

26

Etude No 9

Philip Glass

(1994; 3 mins 58 sec)

Glass, American minimalist extraordinaire, wrote his 20 piano studies “to explore a variety of tempi, textures and piano techniques”, but also to help him become a better keyboard player. His music has been arranged for every medium but the piano is his starting point. You’ll know if you want to sit down and hear them all or if one is really quite enough.

Philip Glass. Redferns

27

The Tempest, Op 109: Chorus of the Winds

Jean Sibelius

(1925-6; 2 mins 22 sec)

Sibelius’s incidental music for Shakespeare’s play was one of his last works, before compositional silence all but fell for the remainder of his life. He had already written seven symphonies, every one a masterpiece. In this music, the spirits of the earth and air, Finnish style, are ever present in the strangeness of harmonium, harps and ghostly voices. Who does Sibelius sound like? Only himself.

28

Havanaise

Pauline Viardot

(1880; 4 mins 44 sec)

A mezzo-soprano as well as a pianist who played duets with Chopin, Viardot was a cultural-sexual magnet in 19th-century Paris, an object of infatuation for the writer Ivan Turgenev, as well as the composers Charles Gounod and Hector Berlioz among others. Her delicate Havanaise, based on the Spanish-Cuban habanera dance, dripping with vocal ornament and technical challenge, indicates Viardot’s own skills as a singer.

29

In the Bottoms: IV. Barcarolle (Morning)

Robert Nathaniel Dett

(1913; 4 mins 49 sec)

Dett was born in Canada into a Methodist family descended from escaped slaves, but grew up in America. This sweetly rocking, rhapsodic Barcarolle (Morning) is part of a suite depicting times of day in African American life in the river bottoms of the south. Dett mixed romantic idioms with the rhythms of folk music, and the spirituals he assiduously – and vitally – collected. He was long forgotten, but no longer.

30

Petrushka, Part I: The Shrovetide Fair

Igor Stravinsky

(1911; 5 mins 9 sec)

Shrove Tuesday is on the horizon. Stravinsky’s ballet about the loves and losses of three puppets was written for large, spectacular orchestra but the recommendation here is the two-piano version. Imagine a carnival bustle of sideshows, ferris wheel, food stalls and a carousel. The festive energy is irrepressible. This is your warm-up for the greatest work of the 20th century: Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

31

Vespers for a New Dark Age: VIII, Postlude

Missy Mazzoli

(2015; 4 mins 35 sec)

So long, January. Mazzoli’s Vespers for a New Dark Age negotiate a rich range of instrumental and electronic effects, reimagining the traditional vespers prayers (try Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 for choral glory) to explore ritual in modern life, embracing technology and spirituality. Mysterious clouds of instruments and voices scud across the sonic spectrum. With this eerie postlude your diet is over.