It’s a Great Age for Jazz, but Don’t Call It Golden

Leave open the possibility that the music can get even better rather than locking it in a gilded frame.

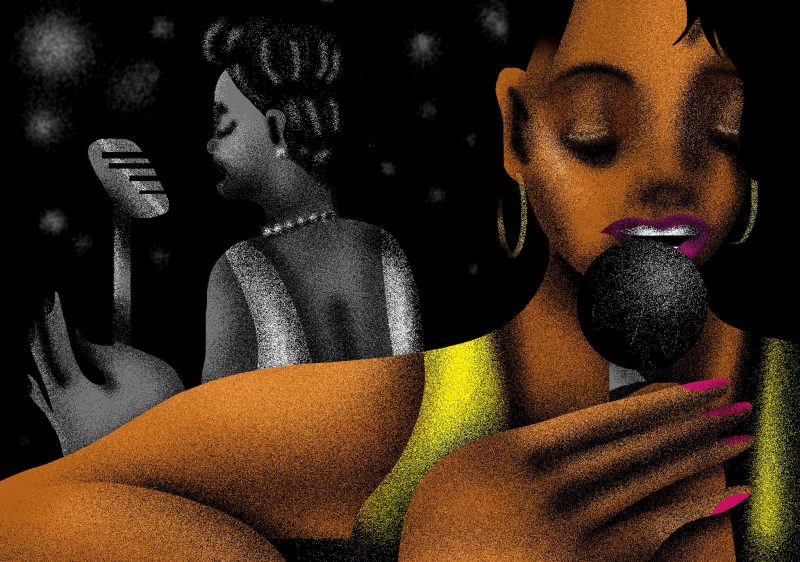

When was the last time you saw a jazz musician electrify a crowd? For me it was a couple of weeks ago, during Esperanza Spalding’s exultant concert at Town Hall, in midtown Manhattan. Singing the deftly intricate songs from a new album, “12 Little Spells,” she was the picture of vital intensity well before the encore, when she re-emerged in a jumpsuit emblazoned with the catchphrase “Life Force.”

Ms. Spalding is exceptional in every sense of the word, but she’s also part of a cresting wave. The music we call jazz has been undergoing an explosion of creative possibilities, carried out by musicians with an impressive range of new skills and ideas. Some of them have found traction with impassioned young audiences, achieving a rare balance of popular success and critical approval — enough, in some corners, to bring talk of jazz’s new golden age.

I just wrote a book about jazz in the new century, so I might be waving that banner, too. The music’s plurality of style, embodied by Ms. Spalding and so many others, amounts to an extension of the jazz tradition rather than any kind of heretical crisis. The music is meant to evolve, and we’re in the midst of its most wildly adaptive, thrillingly unruly evolutionary phase in some 40 years.

So why do I balk whenever someone declares that jazz has entered another golden age? On some level it’s reflex: a resistance to hyperbole, and an awareness that whatever my convictions, we don’t have enough distance to see our moment with total clarity. On some level, too, it’s wariness about any exercise that weighs one era against another, brushing aside the broader context.

But I have even more fundamental reservations. To declare a golden age is to freeze a moment in time, locking a gilded frame around its edges. It ends up crowning some figures and crowding out others, distorting a reality that’s far richer and messier in practice.

If you have even the most casual relationship with jazz, you’ve probably reckoned with this issue. Golden-age thinking feels woven into the fabric of the art form. Around this time 60 years ago, “The Golden Age of Jazz” was the theme of a landmark issue of Esquire, which gave us the Art Kane photograph known today as “A Great Day in Harlem.” Elsewhere in the issue, the novelist John Clellon Holmes assured the reader that “you are living in the most exciting, most creative, and perhaps most crucial age through which our native music has ever passed.”

His pronouncement is familiar and humbling — and hard to argue with, in historical terms. I’m in my early 40s, and like many jazz fans of my generation I spent a substantial portion of my early listening experience fighting the feeling that I’d missed out on all the good stuff. The music industry fed this perception with a steady outpouring of classic albums reissued on CD. And the jazz media seemed to present every emerging young face as a jazz-historical avatar: a new Miles, a new Ella, a new Billie.

We’re mostly beyond that mode of thinking, notwithstanding the occasional article hailing Kamasi Washington, a tenor saxophonist with a vaulting, athletic style, as some kind of spiritual successor to Pharoah Sanders. I’ve seen Mr. Washington a number of times, most recently raising the rafters at Brooklyn Steel, and I’d venture to say that few in the crowded room had any historical marker in mind; we were caught in an onrushing present tense.

One of this year’s most heralded jazz artists, the Chicago-based drummer Makaya McCraven, has made a point of pushing back against any reductive narrative of succession; he likes to emphasize the communal aspects of his art, and all the ways jazz history forms a continuum. This month he played a sold-out show in New York, to a standing audience that often hollered its approval. His band featured a few other breakout stars, like the British saxophonists Shabaka Hutchings and Nubya Garcia, and the whole evening registered as a triumph.

At one point I noticed Ravi Coltrane in the audience, watching intently. An excellent saxophonist and bandleader, he’s also the son of two jazz titans — the saxophonist John Coltrane and the harpist and keyboardist Alice Coltrane — and a cousin to the electronic music producer Flying Lotus, whose Brainfeeder label receives a lot of the credit for jazz’s latest spark with young audiences.

I called Ravi a few days after the show, to hear his impressions. “I felt a lot of pride, really,” he said. “There’s something very enduring about this music. I spent a lot of time watching my mother drag her harp onstage, playing in very similar environments, with a spiritual vibe moving through the room. It felt like a beautiful affirmation of what a lot of artists from that period did.”

Still, Ravi chuckled when I brought up the notion of a new golden age. “There will always be great players,” he said. “Sometimes the wave goes up, and we have what seems like an insurgency of new talent.” This is a great time for jazz, but it’s important to leave open the possibility that it can get even better.

Flashing back to that issue of Esquire, from January 1959, I often trip over an essay by Ralph Ellison, “Time Past.” A reflection on the glory days of Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, which were then only a dozen or so years in the rearview, the essay rings in a nostalgic key. “It has been a long time now, and not many remember how it was in the old days,” Ellison begins, as if to evoke a crawl of covered wagons on the plains.

He was writing in a mild deadpan, but the pining was genuine. And it’s worth remembering what followed, as 1959 got underway. Albums like Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue,” the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Time Out,”Charles Mingus’s “Mingus Ah Um” and Ornette Coleman’s “The Shape of Jazz to Come.”

It’s tempting to see those landmarks as a fulfillment of certain grand pronouncements. But the musicians weren’t setting out to justify the rhetoric of a golden age. Then as now, they were just pursuing their interests, filtering out distractions, doing the work. Their focus was pointed firmly on the road ahead.