Why is the orchestra seated that way? An Explanation

by James Bennett, II

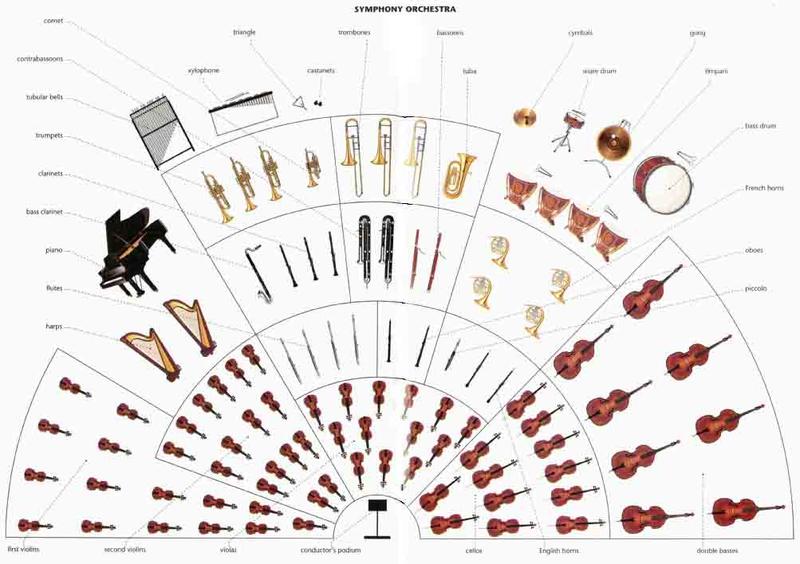

Why don’t the oboes and tubas sit in the front of the orchestra? Why don’t flutes and first violins swap positions, or — in what would be the coolest configuration, let’s be honest — bass trombones and contrabassoons sit right up front with the conductor? Why is there even a conductor at all?

There’s pretty much a reason for why everything we experience is the way it is (whether or not those are good reasons is an altogether different discussion), and the orchestra’s seating arrangements are no exception. In a recent article for The Florida Times-Union, the Jacksonville Symphony music director Courtney Lewis gives a brief explanation for why the musicians sit where they do. It’s an interesting look into acoustics and the history of music and performance.

Lewis traces the growth of orchestras, hinting at the role industrialization and urbanization played in getting the orchestra to where it is now. Also discussed is the emergence of the conductor as a fixture of these increasingly large orchestras; he cites Hector Berlioz and Felix Mendelssohn as two early examples of the dedicated conductor.

As for the current “traditional” seating arrangement, Lewis reveals that it’s a fairly recent development. Until the 20th century, the first and second violins were usually seated opposite each other, creating “an 18th-century stereo effect” with the two sections playing off one another. And then came the influential conductor Leopold Stokowski, who among other things served as the music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra:

(That’s him at Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic.)

Fantasia conductor:

And Looney Tunes parody subject:

Among the many places Stokowski left his mark was in his experiments with orchestra seating, including the one that Lewis calls the “Stokowski shift.” He explains:

“Stokowski was a great experimenter, and he tried seating the orchestra in every imaginable way, always trying to find the ideal blend of sounds. On one occasion he horrified Philadelphians by placing the winds and brass in front of the strings … But in the 1920s he made one change that stuck: he arranged the strings from high to low, left to right, arguing that placing all the violins together helped the musicians to hear one another better. The ‘Stokowski Shift,’ as it became known, was adopted by orchestras all over America. In England, Henry Wood favored the same arrangement, leading to its adoption across the UK.”

This arrangement, though not immensely popular overnight (Lewis refers to German and Austrian attitudes as “unimpressed”), did gain influence and staying power. The result? Composers began writing music that took advantage of this setup.

We’ve grown used to this high-to-low seating, but Lewis writes that he tries to adjust the string section to fit the historical context of the piece being played. Of course, there is no way to know how older composers intended their work to be performed — let alone how their orchestras sat. But it is worth keeping in mind that the way you see things today is not necessarily how they have always been. Getting the answers to questions you never knew you had can lead to gems like a deeper appreciation for the music, a new excitement for the live concert experience or a 1940 Chicago Tribunearticle about the “radical realignment” of the orchestra.