Why Does Music Make Us Feel?

Why does music make us feel? Although it is a purely abstract form of art, it can still weave stories through the subtleties of the melodies. Even without words, music is able to touch every person in what I believe to be their soul; it is able to strike some internal nerves and help us to relate to one another.

It has been proven that listening to music causes the human body to convey all the symptoms of emotional excitement. Physically, the pupils in the eyes dilate, the pulse and the blood pressure rise and the cerebellum in our brains become active to the point that blood is redirected to our legs. Sound stirs our souls to our biological and spiritual roots.

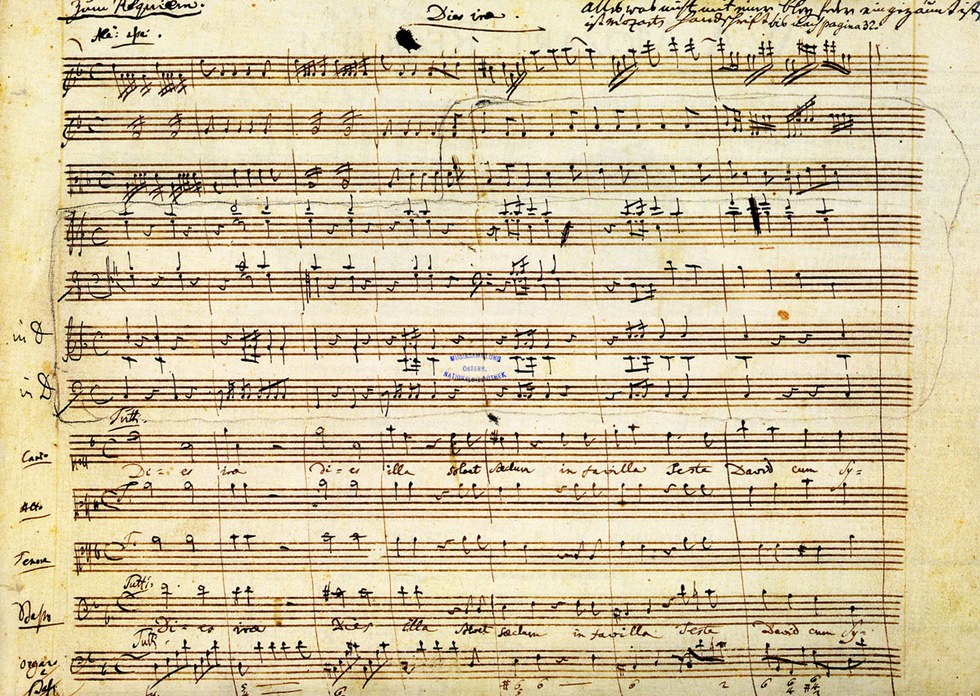

This is exactly what happens during Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D Minor. The piece is an hour long mass for a funeral (Mozart speculated he was commissioned to write it for his own funeral—morbid, I know), and fully embraces the power of choral and orchestral music. Liz Hill, an alto in the Lycoming College Chamber Choir, says that the “Emotion is something out of body almost. Sort of like I’m hearing and feeling something so much bigger than myself, something that actually doesn’t have a word.”

In a study done by a team of Montreal researchers, it was discovered that our favorite moments in a piece of music are caused by an “anticipatory phase,” causing the powerful parts of the music that we wait for to have a euphoric effect on the listener. The researchers suggested that “The reward is entirely abstract and may involve such factors as suspended expectations and a sense of resolution. Indeed, composers and performers often take advantage of such phenomena.”

But why do we feel the way we do when the Requiem Mass in D Minor plays, aside from the physical responses? The only way to answer that is to look at the music itself. Music as an entity is easily seen as a cluster of intricate patterns (music is in essence a mathematical art form), but it seems that the most important and memorable moments in pieces are when these patterns we come to expect break down; when the sound becomes unpredictable and keeps us on our toes.

Often, this is why composers introduce the main theme in the beginning of a piece and then carefully avoid it just enough until the very end, where we are finally able to get an emotional release because the comfortable, expected pattern has returned. According to the Montreal researchers, “The suspenseful tension of music (arising out of our unfulfilled expectations) is the source of the music’s feeling.”

Arguably, the emotions that come from music also arise from the events that unfold in the music itself and how we interpret them. Tenor Joe LeBender says, “The main thing I feel while singing the Requiem is powerful. During movements like Dies Iraeand Confutates when the music is dark and the whole orchestra is playing their hearts out, the tenors have such powerful, operatic lines that soar over the rest of the choir, even though the main theme is loss.”

The meaning of a piece comes from the patterns the composer creates and then casts aside, creating an ambiguity that causes the human mind to want to resolve into clarity. Liz adds, “Even without the text, he paints such a clear picture of the pleading and begging and praying for the safe passage of the soul.”

The uncertainty makes the feeling and propels the story of the composition. It causes the sense of anticipation and euphoria when the familiar sounds return to the piece. It causes the feelings of heroism that Joe feels, the overwhelming sensations of power that Liz feels and the entire spectrum of emotions the audience feels while listening to the Requiem. The emotions behind Mozart’s Requiem give us a brief insight into the mind and soul of a man who lived hundreds of years ago and connects us as listeners to him in a way we never would have thought possible. That is what keeps us listening.