Why Do We Use Italian Words to Describe Music?

In 2007, the ever fashion-forward musician Kanye West boasted “I don’t see why I need a stylist / when I shop so much I can speak Italian.” Mr. West, it appears, has acquired so much Gucci, Fendi, Versace, Prada et al. over the course of his career that he’s confident that during a trip to Italy he’ll be able to communicate just fine with the vocabulary he picked up during those luxury shopping experiences. Nearsighted? Probably, but I’m sure he’s not the first musically oriented person to have this thought.

Even if you don’t know how to read music, there’s no doubt you’ve encountered loads of Italian during your musical experiences. Music is often said to be a universal language, but Italian just might be the language of music itself. It’s everywhere, peeking between the lines and spaces (“these notes are played staccato!”), declaring the sections of multi-movement works (The adagio dragged a bit, but man was that scherzoslammin’). At the opera, we might even find ourselves shouting some Italian after a particularly beautiful aria, showering the singers with bravos, bravas or whatever grammatically gendered configuration may be called for.

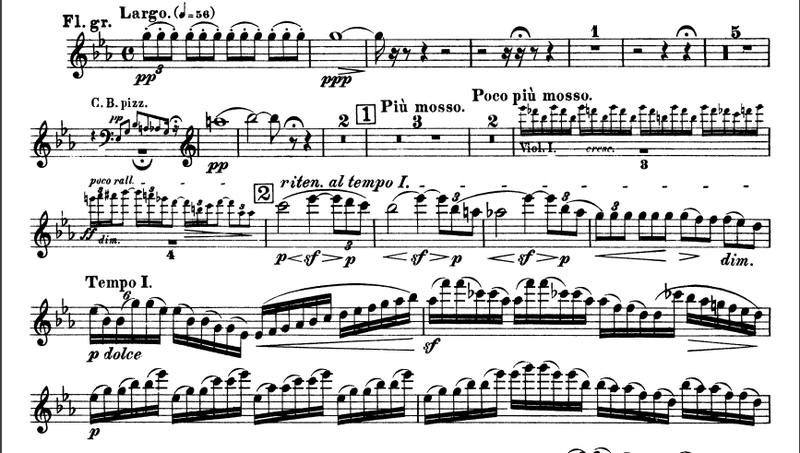

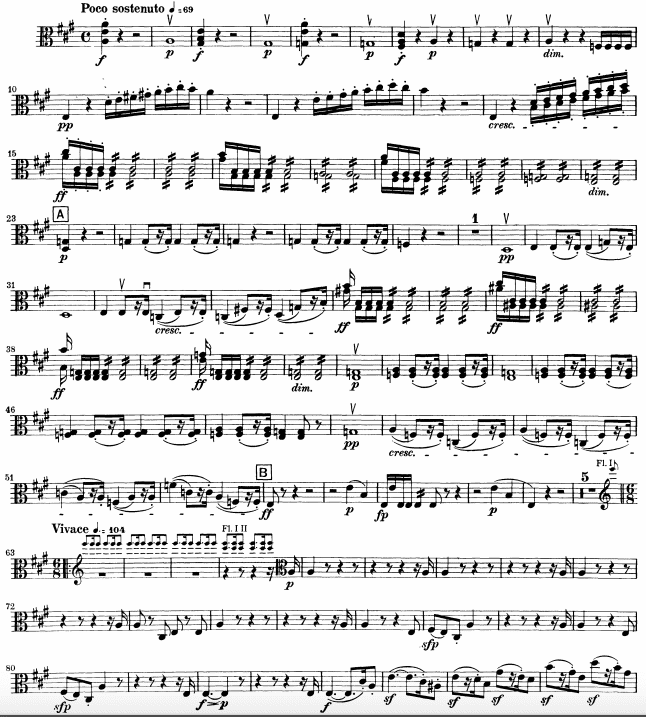

Take a look at the first page for the viola part of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony:

Italian is used to convey virtually everything the musician needs to know to infuse the ink on the sheet with a most vital energy. The tempo, or “time” is set at 69 bpm, and Beethoven instructs the orchestra to play pocosostenuto, “a little sustained”; nice and smooth. The first note is sounded loudly, that is, forte and detached, or staccato. The “v”-like symbol tells the violist to bow upwards, sull’arco; the p marking instructs the musician to play quietly — piano. Crescendos signal to gradually get louder; diminuendosto slowly quiet. After the introduction, the orchestra is to play a bit livelier, vivace. Later on, they’ll be told to pluck the strings (pizzicato) and then return to the bow (arco).

“Concerto,” “violin,” “piano,” “cello,” “alto,” “soprano” and “opera” are all words of Italian origin that have worked their way into the English of today. But why? The answer may be a simple one — habit. Oxford Dictionariesreasons that Italy established a linguistic hegemony of sorts on much of European art music. And it makes sense, considering the number of musical innovations and developments to come out of the peninsula — staff notation from Guido D’Arezzo, musical forms such as the cantata, concerto, partita and rondo; and, of course, the rise of opera. And some of the finest violins and cellos were developed by families like the Stradivari, Guarneri and Amati of Cremona. When that influence began to spread across Europe, the words used to describe them went along too. From Oxford:

When these musical forms and other new ideas about music circulated around Europe, it was only natural that the Italian language went along with them. Hence we end up with German-speaking Johann Sebastian Bach writing cantatas with sections marked as andante.

Of course, Italian isn’t the only language that’s worked it’s way into the musical vocabulary. And honestly, that fact gives the hegemony idea a bit of weight. “Encore” comes from French; the German Wagner gave us “leitmotif.” And we do use those terms when discussing music or holding back emotional tears as we scream at soloists to come back just one more time, please, please. But you can count on Italian to largely take the lead when it comes to giving voice to those spots of ink on lined paper.

Next time Kanye goes to Italy, ask him if you can tag along. He handles the fashion; you can both hold down the music. It might be a trip that’s a tad limited in scope, but when you’re strolling vivace in Versace, that won’t matter much at all now, will it?