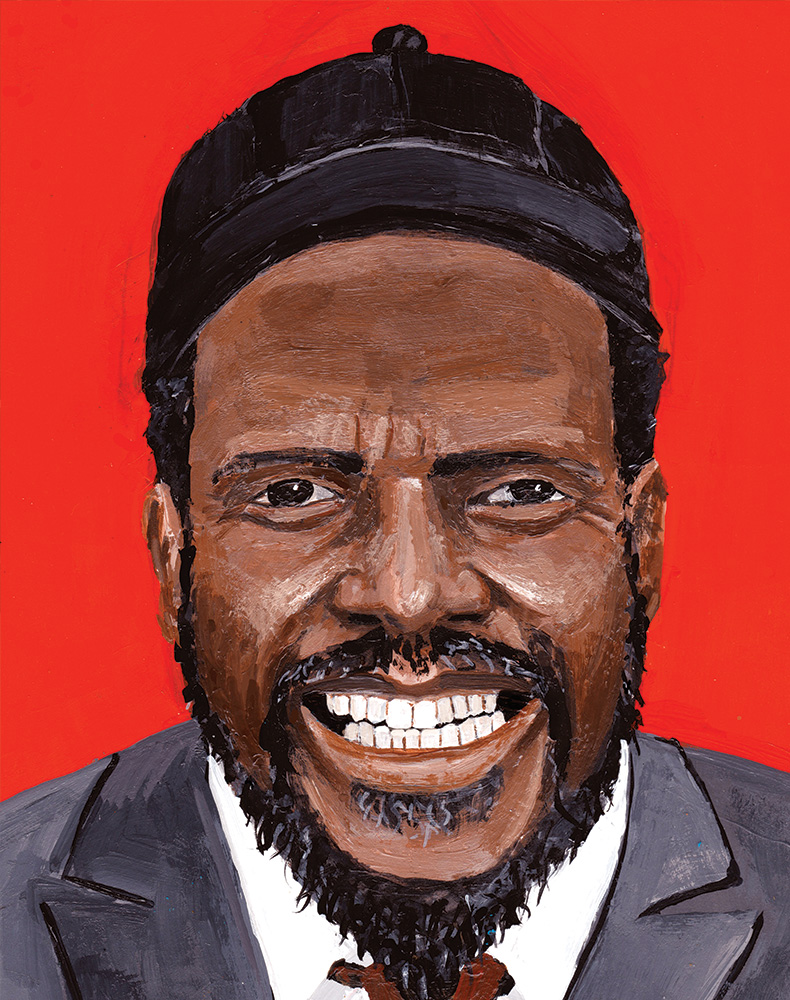

Thelonious Monk: So Plain Only the Deaf Can Hear

How the jazz icon cracked apart the rusted shell of the piano and opened a portal into the breathless, off-tempo grind of being black in America.

In 1964, Thelonious Sphere Monk appeared on the cover of Time magazine. It was a remarkable achievement for a middle-aged black man who had been broke just a decade before. Despite the fact that the virtuosic pianist and bebop originator’s compositions were beginning to be studied by jazz and classical musicians alike, most of his nearly 15-year career had been spent in relative obscurity. The Time cover seemed to mark the end of all that. Churchill had been on the cover of Time. FDR. Clark Gable. This was for-real business. And they didn’t just take a photo. They had a portrait painted: Monk’s profile in a feathered chapeau, his stately gaze off to the distance as though he were surveying the kingdom he ruled. A black man who sometimes played piano with his forearms in portrait on the cover of one of the most serious magazines in the country. In 1964. What the hell.

Consider that Monk was a largely self-taught pianist from a section of New York City that doesn’t even exist anymore. San Juan Hill—reportedly named in honor of its population of former Buffalo Soldiers whose bravery won one of the most decisive battles of the Spanish American War—stood hemmed in by Amsterdam and West End Avenues, 59th and 64th Streets. The blackest section in Manhattan at the time, it was predictably marked for wholesale demolition to make way for Lincoln Center and its subsequent streams of tuxedoed season subscribers. But in its day, it stood as a wry and tough neighborhood of fighters and families, hustlers and musicians, so quintessentially New York that West Side Story was filmed on its streets. This was the soil from which Monk sprang. His family moved there from North Carolina when he was just 4, sealing his fate as a New Yorker.

A quiet but confident child, he fell immediately in love with the piano after taking 15-cent lessons at the community center, and hustled his way into jamming with every local musician he could. He won Amateur Night at the Apollo so many times he was banned by the time he was 13. He attended the prestigious Stuyvesant High School, but dropped out to tour the South as an accompanist for a traveling preacher. Unlike the jazzman who travels north with an instrument case and a dream, Monk was, almost by birth, an apartment dweller, a man utterly at home in the dense and sardonic temperament of Manhattan.

He was already experimenting with his brand of off-kilter boogie woogie by the time he reached his late teens. A master of stride piano, he forged his sound from pieces left by the jaunty traditions of Jelly Roll Morton and James P. Johnson, self-accompanying pianists who insisted you dance rather than listen. But Monk approached this style with a vicious sarcasm that was at once beautiful and contentious. Behold his sharp re-working of the 1925 Vaudeville tune “Dinah,” a piece previously treated as a blithe soundtrack to early Max Fleischer cartoons and made famous by novelty quartet the Mills Brothers. Monk’s take appears on the 1964 masterpiece Solo Monk, released on Columbia Records. He flashes his stride chops to glittering and playful effect, entertaining with the cunning of his right hand, while the left dexterously covers vast stretches of the keyboard. The upshot is a savvy rendering of a goofy love song. A day at the amusement park. A shared sundae and a dollop of whipped cream on the nose. It’s the audio version of those old-timey pictures of lovers posing on a paper moon. But Monk’s tendency to occasionally drop a wrong note—to pound out a dissonant thud in the bass run—lends a comedic, if satirical, edge. The tune, by Harry Akst, written for the vaudeville show “The New Plantation,” has been recorded by Chet Baker, Cab Calloway, Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, and many more. But only Monk’s version unpacks the song’s fluffy innocence to reveal something wry underneath.

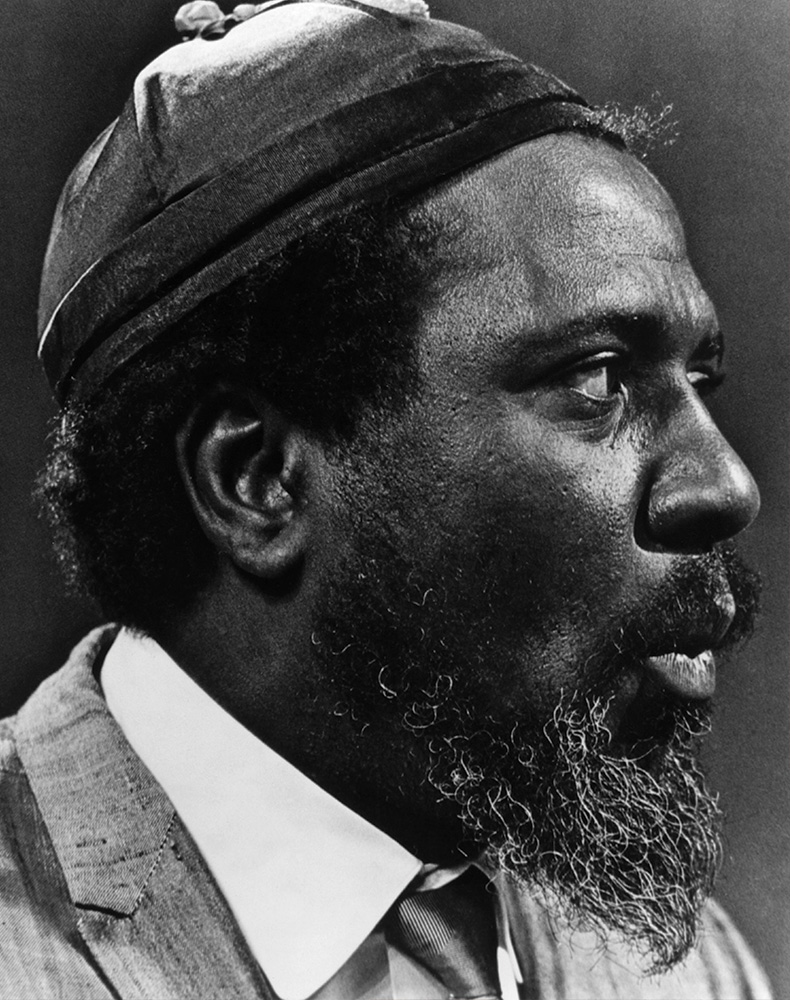

Photo by Herb Snitzer/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

For better or worse, Monk’s public persona was one of extreme, almost mystical inscrutability. He was wildly introspective and capable of extreme focus, often to the exclusion of social niceties like greetings and small talk. He mumbled while he played and sometimes became overwhelmed with a desire to write, reportedly staying up pacing and working literally for days at a time. But sometimes, it was impossible for him to get out of bed. He could be notoriously taciturn, and when he did deign to talk to reporters he frequently parried obvious questions with philosophical games of “Who’s on First?” Frank London Brown learned this when he profiled Monk in 1958 for Downbeat magazine. Brown asked Monk where he thought modern jazz was going. “You can’t make anything go anywhere. It just happens,” replied Monk. His stalwart wife, Nellie, and his precocious adolescent niece both tried to help Brown out by rephrasing the question, but Monk would not be moved. “I don’t know where it’s going. Where is it going?…I don’t know how people are listening”—a wildly paradoxical response from a man whose work defined modern music for generations.

Everything about Monk’s life and work suggests a person unconditionally committed to the world in his head. Even in his poorest days, he never left the house unless cleanly appointed in a pressed suit and tie accessorized with an array of ascots, wild glasses, and funny hats. But while magazines and movies ran with this cartoon version of the scatting hep cat, Monk’s visage was authentically acquired, a product of his unceasing creativity. This desire, indeed, was what drove his offbeat and mesmerizing compositions. Early pieces like “Well You Needn’t,” with its spastic call and response, was laid out on a bed of chromatically rising and falling tones; “In Walked Bud,” a raucous tribute to best friend and mentor Bud Powell; and the Monk standard “Round Midnight,” which managed to fashion purposeful dissonance into a kind of slowly rollicking ethereal bliss, all stood out as pieces well ahead of their time. Not only musically, but in shape and meaning. In vibe. A vast cosmic wink permeated all of Thelonious Monk’s work. You never knew if he was crazy, or if he was just trolling you.

If you want to understand Monk trolling, you have to understand bebop trolling. Prior to the form’s inception, the once fiery swing genre had cooled to a series of bland big bands in dance clubs. The music had become simple, easy to comprehend. One and a two and a three and a four. Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey had taken over, and it was for white people again. Even Duke Ellington and Count Basie, as beautiful as their compositions were, enjoyed what fame they did outside of black communities precisely because they received benediction from the likes of Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, and others; they had to prove they could speak the language of white music in order to be taken seriously. The framers of bebop—Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Milt Hinton, and Kenny Clarke—began to rebel against this idea of “friendliness” in music, perhaps subconsciously at first, but then with greater purpose. They wanted to play music that expressed how life actually felt. Angry, complex. Tragicomic. Emotionally full. They began to experiment with more densely layered chords, stacked high like the levels of a skyscraper: 9ths, 11ths, 13ths, 15ths. Dissonance buried like gems within pockets of harmony. A smaller band with bigger freedom. A feeling that things were slightly off. Asymmetrical melodies that started off one way but didn’t resolve themselves. Didn’t assure the listener that everything was all right. Because everything wasn’t all right. Blacks were routinely beaten for being on the wrong side of town. New York City police forced every jazz musician to carry an identification card without which they were barred from playing. (Monk, by all accounts a generally sober fellow, nonetheless lost his when a car he was in with Bud Powell was pulled and a bag of heroin was found in the glove compartment.) The most gifted musicians in town often died broke and penniless, overdosing while country clubs played handsome fees to white men to perform their compositions. Bebop had chord progressions that took you for dangerous rides without exactly telling where you might be going. Musical cycles that tumbled you up one hill and down another side, landing you in an entirely different place than you began. And it was played fast. So fast, in fact, that musicians that didn’t know what was up couldn’t participate. They would be lost. And that was the point. If you didn’t understand it, then you couldn’t steal it. It wasn’t for you.

This insistence on leaving the less-learned behind was at the core of Monk’s singular and captivating peculiarity. Think of the piano intro to the iconic “Straight No Chaser.” Monk lays out a relatively straightforward melody but continues to plant dissonance bombs at the bottom of each figure. He then leverages the churning characteristics of bebop to return you to this same discomfort again and again at different points in the measure. It’s almost as if he’s testing you, teasing you like an older sibling, training you to hear it again and again until you understand the impartial beauty of its disfigurement, until you finally recognize the delicacy and grace of the perfectly placed wrong note. How spiritually necessary and personally honest it is to do things as they’re not supposed to be done.

Sometimes it seems the entirety of black American music is about this: trying to carve out a space unspoiled by the overbearing whiteness of being. Slave songs were coded messages about escape and freedom. Blues was filled with complex and culturally specific imagery. Jazz expressed an attempt to deconstruct and complicate American band music in a way that captured the violent and frenetic pace of life in northern cities. R&B beat with hidden messages about revolutions and uprising in the ’60s. Then funk generated intergalactic imagery and a colorful form of mystical Egypto-alien visuals to create a world of inaccessible and separatist blackness.

In the early ’80s, hip-hop began as a tenement cultural collage, sly, transmutable, and infinitely self-referential. Run-D.M.C. took the disco goofiness of the Sugarhill Gang and planted it on cinder blocks in burned-out lots. N.W.A. took the Saturday morning b-boy cartoonism of Run-D.M.C. and infused it with the clear-eyed nihilism of the post-crack era. Biggie and Puff took the hole-in-the-shoes hoodism of N.W.A. and let the shit be platinum clean, razor sharp, and fabulous as fuck. Timbaland and Pharrell took Puffy’s gold-plated pinky rings off and let it be nerd-core. Kanye decided you could be therapeutically self-reflective while dropping televangelist-level braggadocio. And then Drake just started bodying people as an unapologetically suburban singing nigga. These contradictions weren’t just to be weird. They were meant to leave your ass behind. If you didn’t understand how these things worked together, then it was not for you. Every moment of this progression consists of a black artist making something that challenges the norm and tries to give life to the specificity of their experience. Every moment imbues the maker with the power that comes when you create music that is direct, epic, and (most importantly) impossible to understand for people that don’t live it. Doing things wrong is often how black people create their own freedom.

But the wizardry of Monk, who is comfortably situated in this 400-year tradition, is that he was as much a brilliant musical technician as he was a brilliant troll. He possessed indelible speed on the keyboard, as demonstrated by his vivid runs, tossed on to the ends of tunes as if to say, Yeah, I can do that shit, too. And his two-handed stride work, most evident on jumpy solo sessions like “North of Sunset” and even midtempo gems like “I’m Confessin,’” distinguished him from contemporaries who favored an aloof comping approach to their solo work—playing chords fully on the left hand. But the most lavish demonstrations of Monk’s aptitude come with his compositions. Probably none more so than his breakthrough album, 1957’s Brilliant Corners.

The title track is legendary, in that it almost caused a fist fight in the studio. Producer Orrin Keepnews had to stitch the final product together from 25 different takes. At one point during the recording, bassist Oscar Pettiford was just pretending to play, miming while the tape was running. He would never speak to Monk again after it was over. They worked on the song for five long, smoke-filled, tense, and probably stinky hours, and still couldn’t nail it. Monk brought it on himself. He was trolling the universe with this hilariously complicated hook, one that makes no sense whatsoever, except for the fact that it’s perfect. Last year, I tried to teach myself to hum it, and it took over three weeks of continuous listening just to get close. And yet what makes this track so good isn’t the technical proficiency it requires. It’s just what the melody means. Climbing and falling, unfolding over itself like a telescopic barroom fractal. And then the whole thing starts double timing. The song has two tempos, a loping 92 bpm passage that feels like stumbling home contentedly drunk—and then suddenly you’re tossed you into a breathless 108 that leaves you panting and looking over your shoulder. The composition knows exactly how much of each speed you can take, and every transition offers well-earned relief. It’s high-intensity interval training for your ears. Monk’s playing on the hook manages to simultaneously lead the procession and trail behind it like a child dropping magnolia petals in a glorious small-town parade.

Photo by Echoes/Redferns

This is the apogee of Monk’s vision. Music that’s insane and gorgeous, droll and dire, ardently crafted to be so perfectly wrong that it robs you of your predictions and replaces them with ever unfolding alms of unexpected rapture. The harder you fight it, the more frustrating it is. Maybe the life work of Thelonious Monk was to crack apart and invert the rusted shell of the piano and open a portal into the bedraggled contradictions and breathless off-tempo grind of being black in America. This was his power over you and over the world. He reveled in confusing the outsider. And when that outsider has enslaved, beat, hung, dragged, murdered, raped, starved, and excluded your people for centuries, then it’s more than a game of intellectual keep-away. It’s an effort for spiritual freedom. But, of course, it’s a short one. Because everything you make will eventually belong to someone else. This is the American Way.

The Time magazine cover story, of course, did not go as Monk might have hoped. The writer, Barry Farrell, treated him as a zoo-ish curiosity, devoting over 5,000 words to describing his idiosyncrasies while only managing to include two or three direct quotes from his subject. Farrell does talk, however about the jazzman’s tendency for what he called “the put on,” which he defines as “a mildly cruel art invented by hipsters as a means of toying with squares.” Having missed the irony altogether, the writer barrels on with his portraiture of Monk as a mumbling, shuffling, sweating savant, rather than one of the most complex composers of the 20th century, and concludes by describing a sleeping Monk in an “Oriental” hat with cabbage on his lapel while his wife prepares ice cream for him. For Monk, who had spent a lifetime fucking with people in as many ways as he could think of—benignly, angrily, feigning ignorance, feigning interest, and most frequently just by subverting expectations—there’s a cruel yet entirely predictable irony to the fact that the most important piece written about him up until that point was written by someone completely unequipped to understand him. Barry Farrell did not grow up in a community of black warriors from a segregated military unit. He did not travel from church revival to small town to make money to help his mother. He did not teach himself to both play and subvert classical piano as a child. He did not have to, as a grown man, ask NYPD for a permission slip to make his art. He did not have to watch the best and most genius men of his generation kill themselves because they did not want American racism to do it first. But what the 28-year-old Farrell did have was a pen and a national magazine cover on which to explain his understanding of this man almost two decades his senior.

But to many of us who live lives of broken chords and impossible dissonance that nonetheless create wild and beautiful music, Monk’s message was as straightforward as the black keys on a piano. In the 1958 Downbeat profile, Frank London Brown reported that Monk’s wife Nellie once chided him for his opacity in the public eye. Monk, as usual, saw it differently. “I talk so plain,” he said, “that a deaf and dumb man can hear me.”