The oldest surviving oud?

By Karim Othman Hassan

To date this instrument is the oldest Arab oud we know, and it may be the oldest surviving Arab string instrument at all. Its significance is all the greater for its having 7 double courses, which means that we can refer to it as an oud al mukmal, the term used for the oud introduced and described by Mahmoud bin Abdel Aziz (grandson of theorist and musician Abd al-Qadir al-Maraghi). ‘Mukmal’ can be loosely translated as ‘extended’, in distinction from the 4-double-course oud al qadim (the old oud), and the 5-double-course oud al kamil (the complete oud), and 6-double-course oud that Maraghi referred to as the oud al akmal (most perfect oud). The oud mukmal was once extremely common. (You can read about this one’s adopted home in Belgium here.)

Daniël Franke refers to the instrument as ‘ūd-i mukmal and writes as follows:

The 7-course ‘ūd-i mukmal as introduced by Marāġī’s grandson Maḥmūd b. ‘Abdal‘azīz (see Maqāṣid al-adwār, Ms. Istanbul, Nuruosmaniye 3649, fol. 5b–6a, written in 908/1502) was tuned to a [heptatonic] rāst scale, like muṭlaq instruments [i.e. those with open strings only, like harps], which would be altered (retuned) according to the maqām of the piece played. In comparison with the range and potential for modulation of the [6 course] ‘ūd-i akmal, it seems to be a step backwards [on open strings it would render only 7 notes covering one octave, rather than 35 in two octaves fingered on the regular ‘ūd]. The instrument of M. Mušāqa (Lebanon, early 19th century) and the one described by Villoteau both have 7 courses and are also tuned to a quasi-heptatonic scale, only the order of strings being rearranged to create a sequence of fourths (in Ottoman terminology ‘irāq, segāh, ‘ašīrān, dügāh, newā, rāst, yegāh). If one were to transpose rāst an octave up (gerdānye) and segāh one octave down (kabā segāh) the result would come very close to current Turkish tuning. (Pure gut string setups can not be tuned to any pitch desired; thus octave transpositions might—just as on the European theorbo—be a result of the string material).

(See Daniel Franke, ‘Musikinstrumente’. In Museum des Instituts für Geschichte der arabisch-islamischen Wissenschaften: Beschreibung der Exponate (I). Frankurt/Main, 2000, p.12).

It is immediately obvious from the first glance that the example we have – in contrast to the description of a very similar instrument by Villoteau – is not, by today’s standards, of a very refined craftsmanship. That is not to say that the woods used were of a poor quality. The face seems to have been made from 4 pieces of wide-grained spruce or pine, and there are no major cracks to be seen on it.

The rosettes (shamsiyat) are made from coloured hardwood, very simply sawn or gouged out and placed straight onto the face, rather than glued in from inside as has become common more recently. For today’s thinking, the two smaller rosettes (known as qamarain, ‘two moons’) are positioned very close to one another. The elegantly curling bridge glued onto the face seems to have had no continuation in the tradition of late 19th– or early 20th-century ouds. Between the bridge and the rosette is a pickguard (raqmah), probably made of goat or fish skin. The face extends onto the fingerboard a little, as was common on European renaissance lutes.

The body is constructed from 23 ribs of dark wood (perhaps rosewood or kingwood) and strips separating them in a lighter wood (perhaps beech or maple). The construction is very imprecise, probably not conforming to the standards of the time (see again Villoteau’s example). At the base, an unusually large end-clasp decorated with ornamental filaments covers the join in the ribs. This prevents moisture entering the body and also protects the right playing arm from any sharp edges.

Both this large end-clasp and the straight peg-box with its 14 pegs (possibly made of beech) are again more reminiscent of a Renaissance lute then an oud. On the reverse side of the peg-box are wooden filaments arranged in a herringbone pattern. This continues along the back of the semi-circular neck, which widens out towards the body.

The fingerboard has a frame, which may be compared with later Egyptian and Istanbul-made ouds. The frame model is distinct from that of ouds made in the Levant, which at the end of the 19th century present insets of garlands and other floral patterns in art nouveau and art deco styles.

The outermost pairs of strings lie partially beyond the fingerboard. This conforms to the way of playing 7-course instruments described by the Lebanese historian and musician Mikhail Meshaqa (1800-1888), according to which only 4 of the courses were much used. (For Meshaqa’s writing on the subject see Eli Smith and Mikhail Meshakah, “A Treatise on Arab Music, Chiefly from a Work by Mikhail Meshakah, of Damascus” in the Journal of the American Oriental Society 1.3 (1847), p.208.)

The Museum in Brussels conducted some restoration work in 1999 and photos taken at that time allow us to learn about the inside of the instrument. The block at the top is hollowed out, and the one at the base is filed right down in the interest of reducing weight, a standard practice into the early 20th century. There is no sign of a dowel or dovetail joint on the upper block. The ribs are stabilised by strips of white paper.

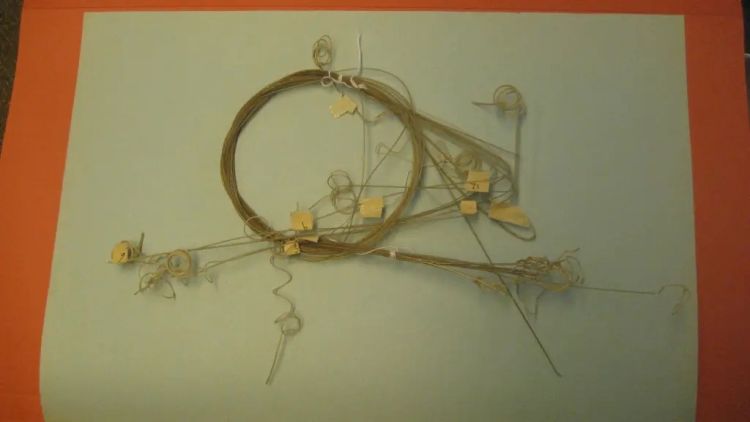

Six parallel crossbeams are glued onto the underside of the face. Two are above the large sound hole, another runs through the centre of the rosette, a further one is located between the large and 2 small rosettes while two others are most widely spaced from one another and frame a large surface below the bridge, supporting resonance and responsiveness. Overall, the bracing is very thin and sparse, suggesting that the oud was designed only for very low string tension. This would also explain the absence of a stabilizing component between the top block and the neck. The strings preserved from the 1999 restoration are likely to be original.

For more about the life of this oud read ‘Alexandria to Brussels, 1839‘.

This text was translated from the original German by Rachel Beckles Willson.

Thanks to Saskia Willaert and Joris De Valck of the Museum of Musical Instruments in Brussels for facilitating detailed research into this instrument.