The Beat Goes On: A Short History of the Metronome

The musician sent home to practice with a metronome confronts in this prescription an absentminded chaperone. It sits on the stand and clucks a rigid beat regardless of whether the player, afflicted with an inability to keep a steady tempo, deigns to follow it. For the musician yet to play a piece in the time she wishes to, the metronome can be a useful straitjacket no less begrudgingly put on.

The tenacious timepiece seems to have ticked through time immemorial, but its form and application to musical life were hundreds of years in the making, beginning with the 16th-century scientist Galileo’s discovery of the pendulum’s isochromism: regardless of amplitude, the pendulum will take about the same amount of time to complete one period, or back-and-forth swing. This discovery could be applied to timekeeping, Galileo realized, foregrounding the invention of the pendulum-powered clock by Christiaan Huyghens in the 17th century and George Graham in the 18th. In 1696, Étienne Louilié, a French musician and pedagogue, was reportedly first to design a metronome with an adjustable pendulum, though his invention was soundless and required the user to keep it in view. Plaguing Louilié and his contemporaries was the problem of creating a metronome that would beat slowly enough to keep the tempo of many classical pieces, often at a mere 40 to 60 beats per minute.

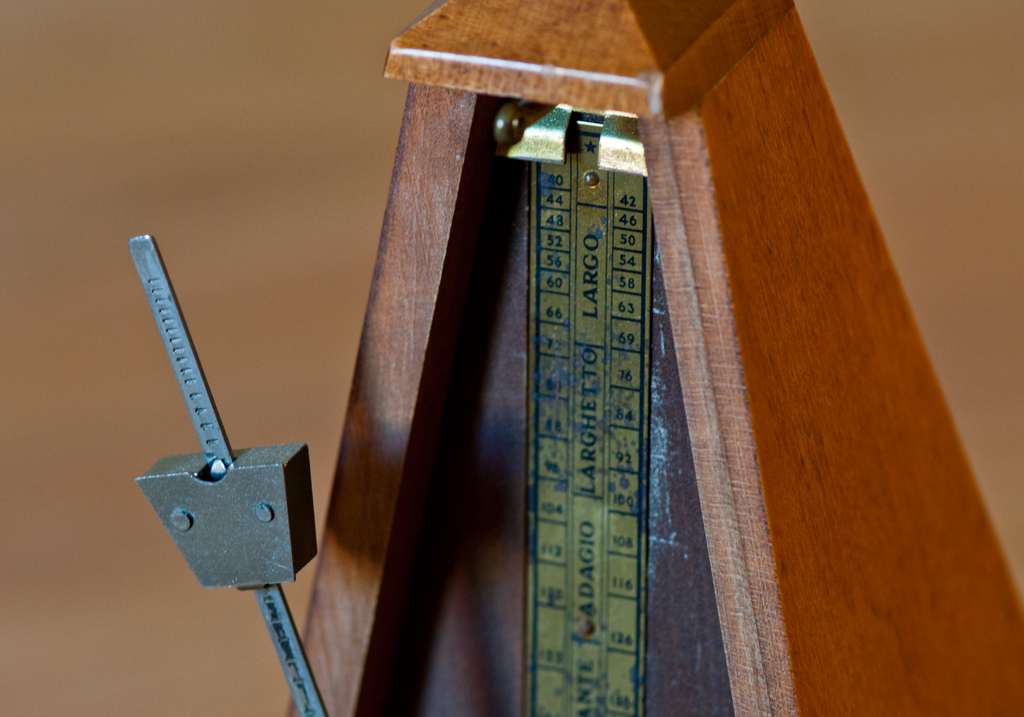

In 1814, the German inventor Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel developed a “musical chronometer” capable of keeping times fast and slow, but he failed to patent his device. In 1816, the tactless tinkerer Johann Nepomuk Maelzel — perhaps best known for his invention of the Mechanical Turk hoax — copied Winkel’s design and, claiming it was his own, established a name for himself on the success of what he dubbed “Maelzel’s Metronome.” The metronome was housed in a wooden pyramid, and could be adjusted by moving a small steel marker affixed to the pendulum up and down. Beethoven, taken with the device, became the first composer to give his pieces metronome markings, and even pledged to do away with indicating such indefinite tempi as “allegretto.” (Maelzel was also an inventor of musical instruments. After some convincing, Maelzel’s friend Beethoven wrote Wellington’s Victory, or, the Battle of Vitoria, for Maelzel’s Panharmonicon, a sort of organ that was among the first automatic playing machines, but the orchestration proved so elaborate that it defied Maelzel’s best attempts to create an instrument substantial enough to play it.) The metronome would go through countless iterations — including, in 1894, a metronome that could mimic the motion of a conductor’s baton — before arriving at today’s comparatively clinical electronic form.

Today we take the metronome for granted; the ballistic beat keeps an uncontested dictatorship over our approach to musical performance. But, explains musicologist Alexander Evan Bonus in an article for Music, Musicology and Music History, the metronome was not always considered an unimpeachable overlord of musical time. “Indeed, the metronome’s history is more accurately the history of musicians’ relationships tometronomes,” he writes. After the debut of Maelzel’s invention, critics came to describe conductors they considered inexpressive as “behaving like metronomes”; the metronome became a symbol of musical ineptitude and incomprehension.

Yet, as civilization’s mechanical prowess accelerated through the 20th century, mechanical devices like the metronome became increasingly acceptable, even desirable arbitrators of “normal,” efficient behavior. Modernist composers of the 20th century, like Stravinsky and Bartók, wrote music demanding stringent rhythmic precision, and conductors obliged, forming the basis for a pro-metronome attitude that has somewhat prevailed among performers and pedagogues. Herbert von Karajan himself claimed to have trained his brain “with a metronome” such that he was capable of walking at 120 beats per minute and singing at 108. The composer Gyorgy Ligeti, with his 1962 composition Poème Symphonique, for 100 mechanical metronomes — each set to a different speed and to conclude when the last metronome has finished — took this modern interest in metronomes to perhaps its most literal extent.

In 1923, the artist Man Ray affixed a photograph of an eye to the arm of a mechanical metronome and called the resulting readymade “Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed).” The metronome would sit in his studio and watch him paint, he explained — a presence that grew all the more ominous when he replaced the original eye with the eye of his ex-lover, Lee Miller, who left him in 1932. Fifteen years later, when a group of student protestors calling themselves the “Jarivistes” stormed the Dada exhibition in Paris, where the artwork was on display, one whipped out a pistol and shot the metronome. It was not the denouement Man Ray, who went crying after the protestors, had planned for his object — the artwork’s accompanying text specifies it meet its end by a hammer’s blow — but it nevertheless fulfilled his terms, and many a dream of music students everywhere.