Six composers who were their own best teachers

We often think of talented musicians as folks who start young and advance their skills via the finest education available to them. While this is certainly true in some cases, there are plenty who realized many of their artistic capacities without the aid of specialized instruction, like…

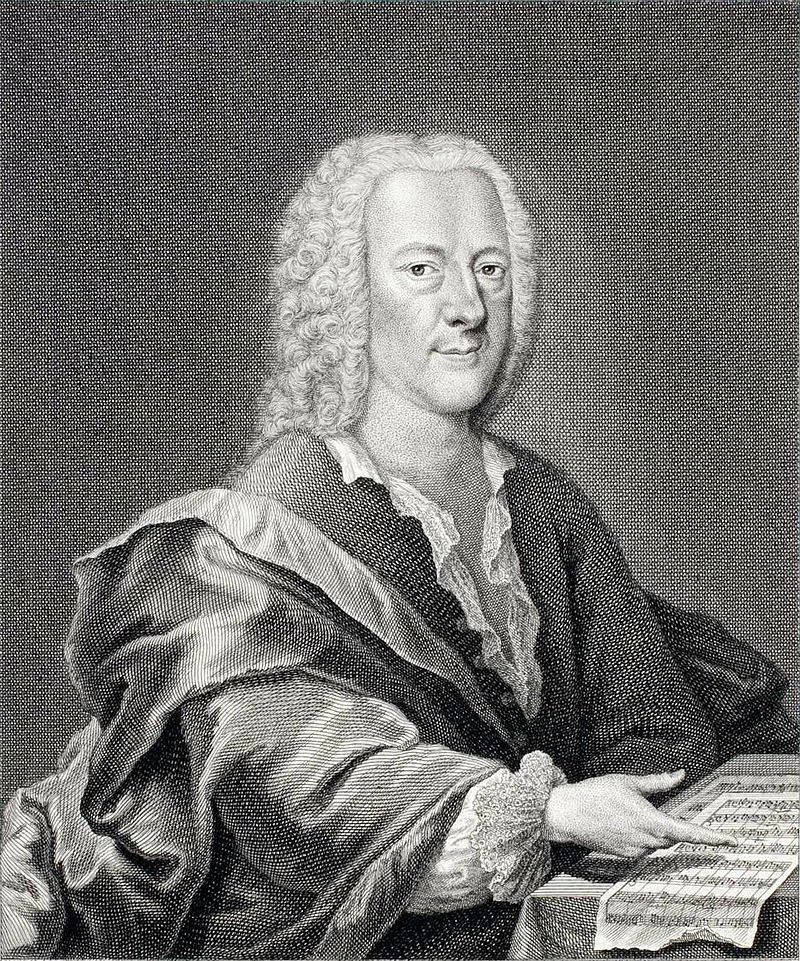

Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767)

Unlike his famed contemporary Johann Sebastian Bach, Telemann didn’t have a musical family to share some of their own creative secrets. The late-Baroque composer was quite educated, but for all of the fine schooling he received, music was never in the mix. He enrolled in law school fresh out of his teens, but his studies took a backseat to music — something he loved so much that he taught himself not only composition, but also several instruments (he could make his way around the viola, recorder, oboe, violin, viola da gamba, chalumeau [the clarinet’s predecessor] and keyboard). In 1723 he was even offered the job of concertmaster at the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, but because he recognized the value of his skills, he declined after his potential employers wouldn’t provide what he believed was fair compensation. (Interestingly enough, the position went to his good buddy Bach.)

William Billings (1746–1800)

If there’s one thing to know about William Billings, it’s this: the man loved singing. (Presumably) on the street, in the bath and especially at church — it didn’t really matter to him at all where he sang, as long as he could. There was only one problem: the singing you’d hear in Boston churches at the time left a lot to be desired. In 1769, Billings began teaching at singing schools, night-time choir rehearsals in area churches. While he didn’t invent the concept, Billings’ efforts led to a New England singing school boom, and they eventually grew beyond the confines of the church and led to the development of singing societies, clubs and competitions. All of these newly-formed choirs needed songs to sing, and composers were more than willing to oblige — leading to an explosion of American sacred song. Also a self-taught composer, Billings wrote a number of anthems and hymn settings. The good news is that they were super-popular. The bad news was that they were so popular, 18th-century copyright law couldn’t keep up, and his tunes would often show up in competing hymnals that often neglected to credit Billings.

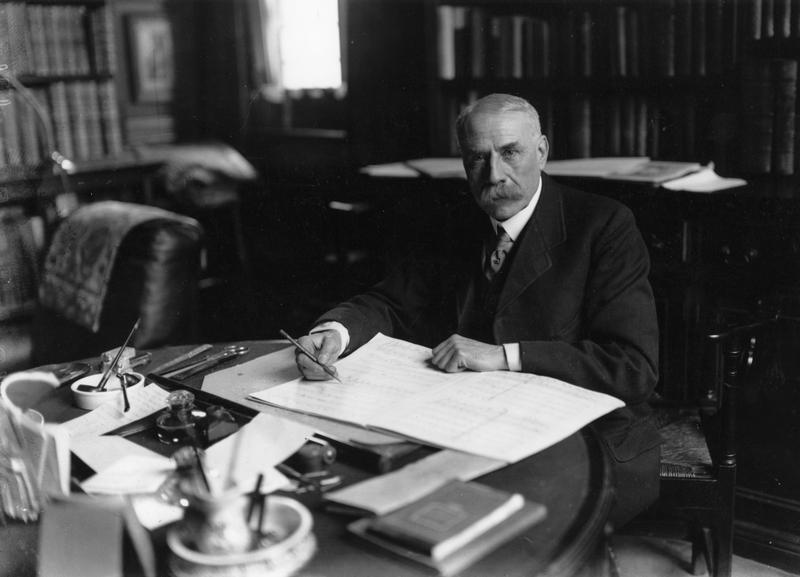

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

It is a little ironic that Elgar, the man who wrote the music used at seemingly every American graduation ceremony, dropped out of school when he was 15, and had little formal education in what would become his profession. While he was a talented violinist (the only instrument for which he received any training), bassoonist and organist, he was a self-taught composer. After working for a few years in London, he moved to Malvern in 1891 and began exploring what he could do with a pen and some manuscript paper. The following years saw him produce two of his most well-known works, Lux Christi (1896) and the Enigma Variations (1899). He was knighted in 1904, and followed up on that honor by serving as the first professor of music at the University of Birmingham.

Amy Beach (1867–1944)

People around her knew that, even from a young age, Amy Beach was special. She taught herself to read at age three (that alone is enough foreshadowing to signal the success and talent of a future autodidact), began composing at four and piano studies with her mother shortly thereafter, and by seven was playing Chopin, Beethoven and her own pieces in recital. She married at 18, and although she had a promising start as a concert pianist, her husband demanded she stop performing in public. So Beach got to composing — teaching herself all there was to be taught, religiously analyzing scores from older composers and studying Berlioz’s Treatise on Instrumentation … and translating it into English. After her husband died in 1910, Beach traveled across the Atlantic, where she had a successful run of concerts in Germany. Upon her return to the U.S. on the eve of World War I, she was made a fellow at the MacDowell Colony and used her status to encourage young composers, especially women.

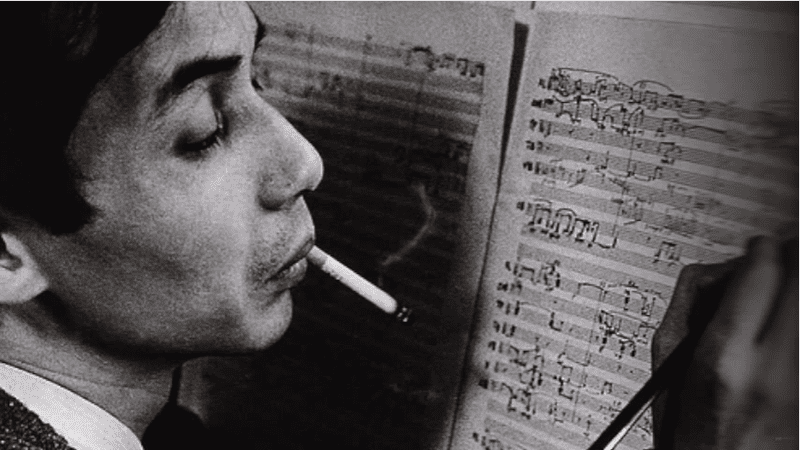

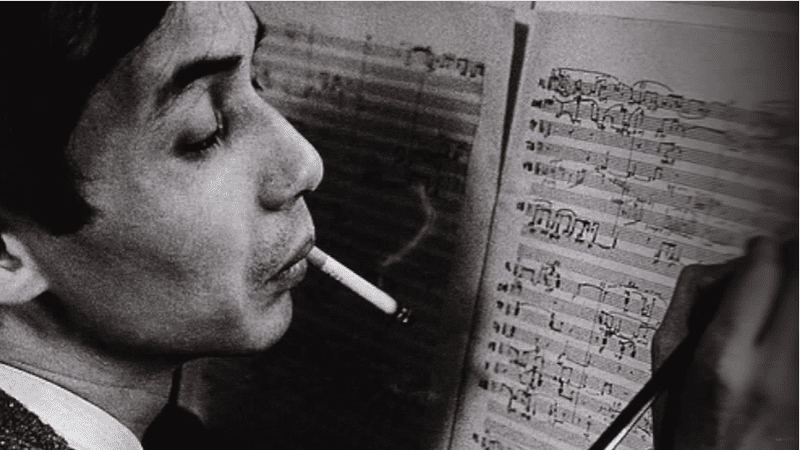

Tōru Takemitsu (1930–96)

Born in Japan, Takemitsu moved to China as an infant. He returned to Japan in 1938, but in 1944 at age 14 (one year before the end of World War II) he was conscripted into the Japanese armed forces. Western music was banned by the government, but as a young soldier he heard a recording of the popular French song Parlez-moi d’amour. After the war, when he was 16, he fell in love with Western classical music and decided to try his hand at composing, despite lacking any kind of formal training. Takemitsu’s creative path is indicative of what can happen when you just listen. He allowed himself to be heavily influenced by composers like Debussy (who he called a mentor), and there’s an unmistakable impressionist vibe in Takemitsu’s music, something he achieved by blending together sounds from both sides of the Eurasian continent. He found a champion in Stravinsky, who heard his Requiem in 1959 and gave it the finest of reviews, which helped launch his international career.

Iris ter Schiphorst (b. 1956)

Schiphorst got a relatively late start to composing, but she is self-taught and draws upon the variety of sounds she’s encountered along her musical journey. As a young child, she played classical piano, but in her early 20s she picked up drums and the bass and started to play in rock and electronic bands. Schiphorst wanted to be a dancer in her youth, and during an interview with the London Sinfonietta she explained how dance and music are linked for her: “When I was a child I loved listening to music and I loved to dance. So the connection between music and movement is one of [the things] I really, really love … If I’m touched by something in life, I’m moved, and I want to express that in music.”

WQXR interns Benjamin Farrell and Emily Spector contributed research for this post.