Some people can see sound, or taste color. Does it make them more creative?

This is something of what life can be like for those who experience synesthesia, a condition in which two or more senses are coupled together. That means that hearing sound can stimulate visual imagery, or a color can have a particular taste or personality trait.

According to neuroscientist and professor Richard Cytowic, roughly four percent of the population bears the synesthesia gene, which isn’t always expressed. Around one in 90 individuals is an actual synesthete. “Some people are born with two or more of their senses hooked together, so that my voice is not only something that they hear—they might also see it or taste it or feel it,” Cytowic says. And what’s more, synesthetes are usually “shocked to discover that not everybody is like them.”

While there are a variety of forms, not all have been described or documented. According to Dr. Nicolas Rothen, common types, by his reckoning, include: music-color (things that are heard are translated into various hues), grapheme-color (which imbues letters and text with corresponding colors), and sequence-space, wherein sequences like numbers, days of the weeks, or months of the years produce “inducers” (often vibrant spatial arrangements). Cytowic cites some additional subsets of synesthesia that he has noted, including varieties in which flavors or personality traits are paired with colors or sounds.

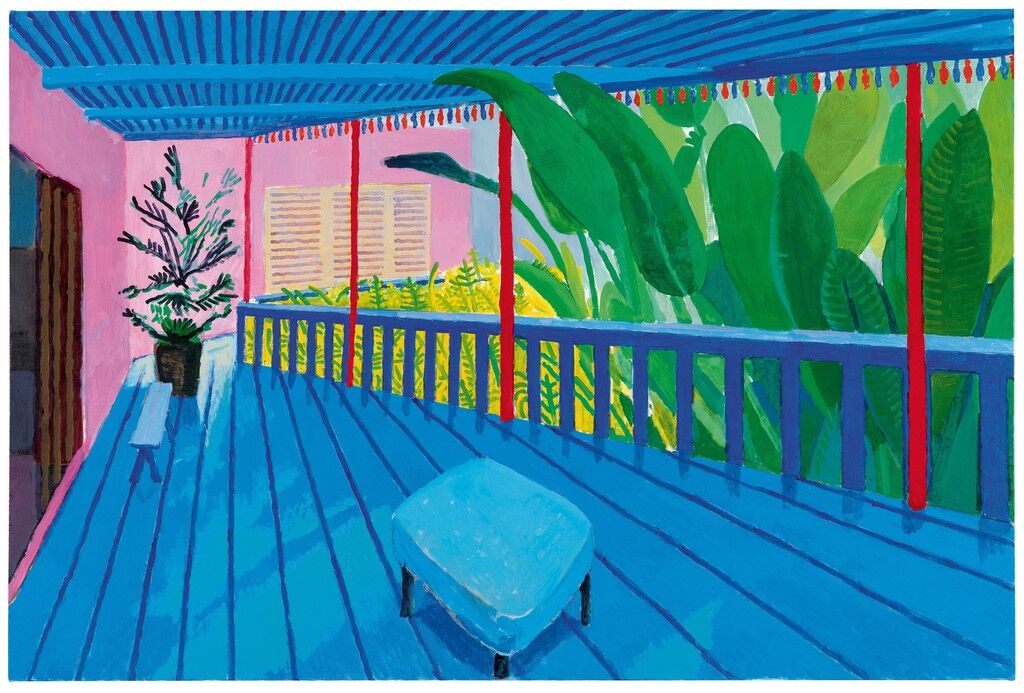

David Hockney Garden with Blue Terrace, 2015 TASCHEN

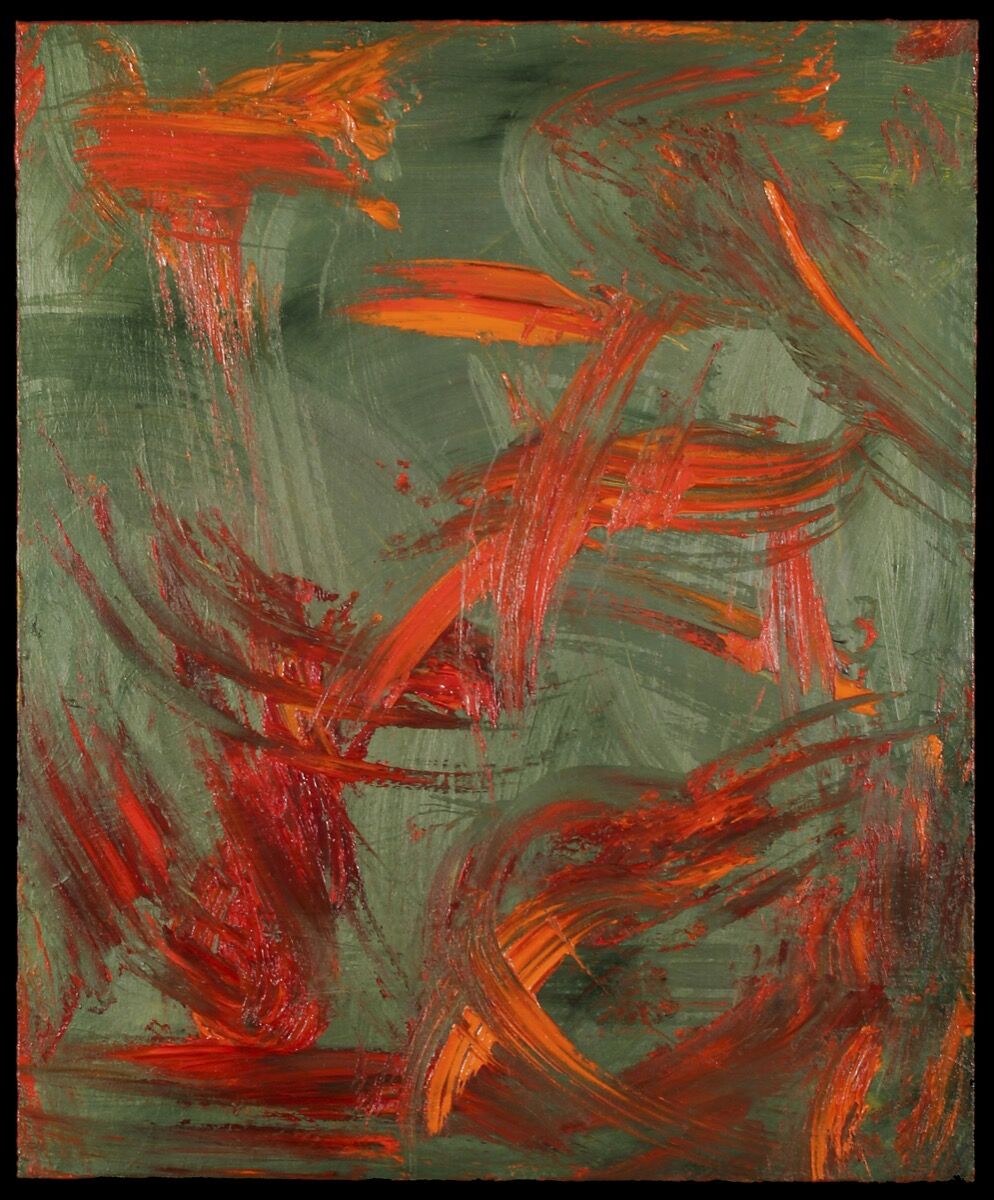

David Hockney Garden with Blue Terrace, 2015 TASCHEN“Pianos are pink, and violins are orange, and a cello is green,” says Carol Steen, a visual artist who has synesthesia and co-founded the American Synesthesia Association in 1995 with Patricia Lynne Duffy. “If someone plays a piano, my first impression is pink, but I can tell you that the last note on the right-hand side of the piano is an incredibly light white, creamsicle kind of character.”

She describes how something simple—like an 18-wheeler traversing a pot-holed street—can generate a wash of colors in her mind, from bright orange to a sort of black-and-white static. Steen describes another instance in which she observed a man playing a Japanese flute; to her synesthetic mind, the music gave the impression of a “metallic green, kind of a sad green, not so bright.” The notes themselves elicited a mingling of reds and oranges rising out of the green background. Years ago, Steen attempted to capture this sensory impression in a painting.

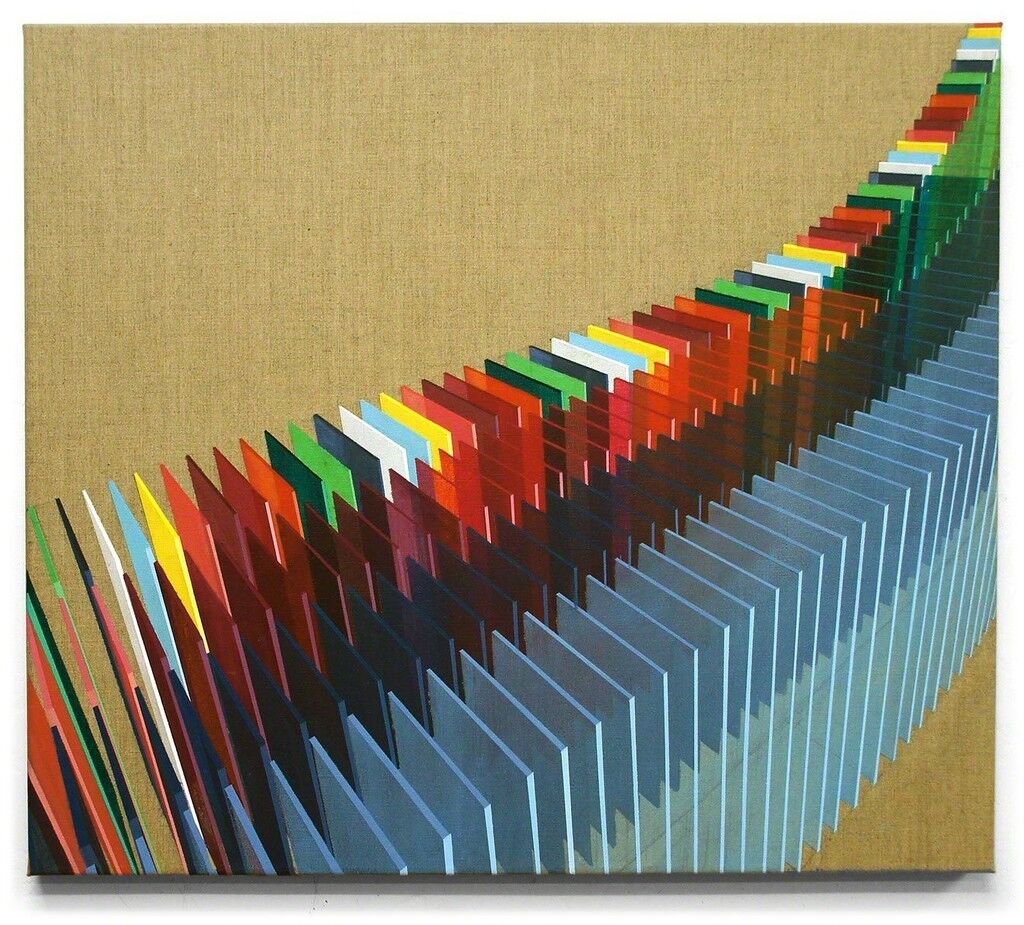

Life with synesthesia can certainly be different for those who experience it. Filmmaker Lucy Cordes Engelman, for instance, perceives time as a tangible, visual object. She thinks of it as “a long orb that exists in a kind of dark—similar to outer space—that I can zoom into and be right in the thick of, or spring outwards, launch off of, and be very far away [from].” That holds for whether she’s thinking of a 5,000-year span of history, or simply recalling the year 1945, Engelman says. In all cases, time for her becomes a three-dimensional “contracting, expanding, undulating, perspective-based timeline that exists in space.” Engelman collaborates with her husband, the painter Daniel Mullen, to create physical manifestations of what she experiences (which is actually what brought them together). To date, the pair has worked on a series of paintings that spotlight “the different possibilities of how time can be depicted and visualized,” Mullen explains, with the artist translating his wife’s synesthetic interpretations. The results (on view in a private exhibition at Uprise Art’s downtown Manhattan space) resemble intricate arrangements of multi-colored glass panes.

Daniel Mullen, 1940-1988 AD,

Daniel Mullen, 1940-1988 AD, So what causes these unexpected phenomena? If not passed down genetically, “it’s a spontaneous mutation,” Cytowic explains. And while we may not yet understand entirely the “evolutionary pressure keeping the gene high in the gene pool,” for now “we can simply enjoy this as a remarkable variation on human perception.”

Often associated with musicians, synesthesia (of varying degrees) has been cited in connection with everyone from Billy Joel and Lady Gaga to Vladimir Nabokov, Duke Ellington, and Stevie Wonder. The New Yorker posited that Marilyn Monroe might be part of the club. Synesthetes also populate art history: Wassily Kandinsky, David Hockney, Charles Ephraim Burchfield, and Joan Mitchell (and, Steen speculates, potentially Vincent van Gogh as well) had synesthesia, writing about and utilizing it in their practices. It has played a part in the inspiration of art movements such as Synchronism and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Dr. Lawrence E. Marks of Yale University makes note of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the 16th-century Italian painter, “who developed a theme for characterizing the notes of the musical scale in terms of different color.” Steen goes even further back, maintaining that there are signs of synesthesia in paleolithic art.

While synesthesia was largely dismissed in scientific realms around the 1930s, research (largely spearheaded by Cytowic in the ’70s and ’80s) and articles (like “Synesthesia and the Artistic Process,” co-authored by Steen and Juilliard art historian Greta Berman) have brought the topic back into the mainstream spotlight. Synesthesia has since been linked to other cognitive areas (like memory); Steen highlights as well that many individuals with autism have a higher chance of being synesthetes. In terms of musicians like Stevie Wonder, whom he’s studied extensively, Marks also speaks of “a connection between perfect pitch and synesthesia.” In representations of synesthesia in visual art, some have cited the appearance of the Klüver “form constant” (recurring shapes and patterns studied by German-American psychologist Henrich Klüver in his research on geometric hallucinations, including those that result from drug experiences).

“It’s just delightful to have watched this paradigm shift.” Cytowic says, “not only in science,” where the previous dogma strictly dictated that “the senses travel along five separate channels and don’t mix,” but also in the larger public perception. “It’s totally changed.”

And what effect does synesthesia have on creativity? Marks explains that creative cognition (essentially an aspect of creativity)—a test of which might ask its subject to conjure as many non-traditional uses for an object like an umbrella as possible—“seems to produce higher scores among populations with synesthesia.” Studies have suggested, as he noted in a 2014 article, “that people with synesthesia do have enhanced creative abilities, creative cognition.”

Cytowic corroborates that “synesthesia is more common among artists than it is among the general population.” And moreover, “even those who aren’t performing artists or, let’s say, ‘working artists’—they [still] will play musical instruments, they’ll know a foreign language or two, they’ll be expert knitters or potters. They’ll have some sort of creative hobby in their lives.”

Plenty of people may experience degrees of conjoined senses, and it’s even been proposed that nearly everyone experiences “weak” forms of synesthesia, a sort of cross-talk between different senses in the brain (Steen mentions the combined smelling and tasting of food as one example). But what constitutes actual synesthesia?

Research has come a long way, but the conception and definition of synesthesia is constantly evolving, and researchers still have a lot to discover in the relatively young field. For instance, Cytowic notes, brain scans alone don’t tell the whole story, and can even be misleading. He mentions an area in the brain (known as V4, or the “color center”) often associated with synesthesia; it tends to “activate” in fMRI scans. “I don’t want people to point to V4 and say, ‘There it is, there’s synesthesia,’” Cytowic cautions. “Many, many other areas are active in this network that supports synesthesia.”

In addition to neuroimaging, though, a variety of behavioral tests can confirm whether someone in fact has synesthesia, Marks explains. A researcher might quiz a potential synesthete about what color associations they have with specific letters of the alphabet. “Then you ask them two years later about the same letters,” he says. “Synesthetes are remarkably consistent over very long periods of time.” Cytowic also adds that the difference between synesthetes—versus those who only claim to be—is that while individual experiences may be quite specific, in general “synesthetes all basically tell the same story” as others who share their version of synesthesia.

But regardless of all the advances over the last 40 or so years, “the study of synesthesia,” Steen says, “frankly, is in its infancy.” There is much more to be done and to uncover, and opinions often differ.

For Cytowic, there are clear benefits to synesthesia enjoying broader discussion. “What it does for the population in general is expand their empathy,” he says. “Once you learn about synesthesia and that people see the world much differently than you do, it opens your mind up, and you’re much more empathetic to other people.”

And the wider acceptance of synesthesia as an actual phenomenon has allowed us to reconsider its effects on artists and artistic practice. The Tate has defined it as an “art term,” and the Denver Art Museum has included itas part of the discussion of Kandinsky’s work. “Wouldn’t it be fabulous to give museums and collectors more information about the pieces they own?” Steen wonders. “To have a fuller understanding of the artist who created them?”

Associate curator of High Line Art Melanie Kress—responsible for the three-person thematic exhibition “Synesthesia,” on view at the outdoor park through March 21st— seconded the value of this nuanced perspective. “Artists always change our relationship to the world,” she says, and for synesthetes in particular, what a “special understanding and relationship to the world that they are able to translate for us.”

Still, some have wondered if synesthesia could act as a detriment, interfering with everyday life or overwhelming those who experience it. While Marks and Cytowic affirmed there are some instances, they are rare. “I’m so grateful for it,” Engelman says of her own synesthesia, but agrees that it can, in some ways, be overwhelming. “It always feels like you’re kind of brimming.”