Maths as an emotional journey: How Marcus du Sautoy is using music to highlight the beauty of numbers

Music and maths have been number-counting bedfellows since the first heartbeat. “There is geometry in the humming of the strings; there is music in the spacing of the spheres,” said Pythagoras. “Music is the sensation of counting without being aware you were counting,” said Gottfried Leibniz.

…1 and a 2 and a 1 and a 2…

Marcus du Sautoy, Simonyi professor for the public understanding of science and professor of mathematics at the University of Oxford, wants to take this connection further in people’s minds. The link between music and maths might be easy to glean in the rhythm of a drum or the harmony of a scale, he says, but it goes deeper than this: in fact, there are things that bind composers and mathematicians which many people would assume are completely antithetical.

“It’s not enough that a piece of mathematics be right. It’s got to move you as well.”

There’s a perception that music is emotional and maths is cold and logical. For Sautoy, this is nonsensical. “Mathematics is emotional because you’re taking someone on a journey with surprises, twists and turns,” he says. “You want them to have the same feeling of revelation you had. It’s not enough that a piece of mathematics be right. It’s got to move you as well.”

To demonstrate such deep-running similarities between music and maths, du Sautoy is collaborating with the composer Emily Howard on a piece that’s being billed as a “poetic translation of mathematical ideas into sound”. The pair is set to perform it at the New Scientist Live event in London on Thursday.

(Above: Marcus du Sautoy and Emily Howard)

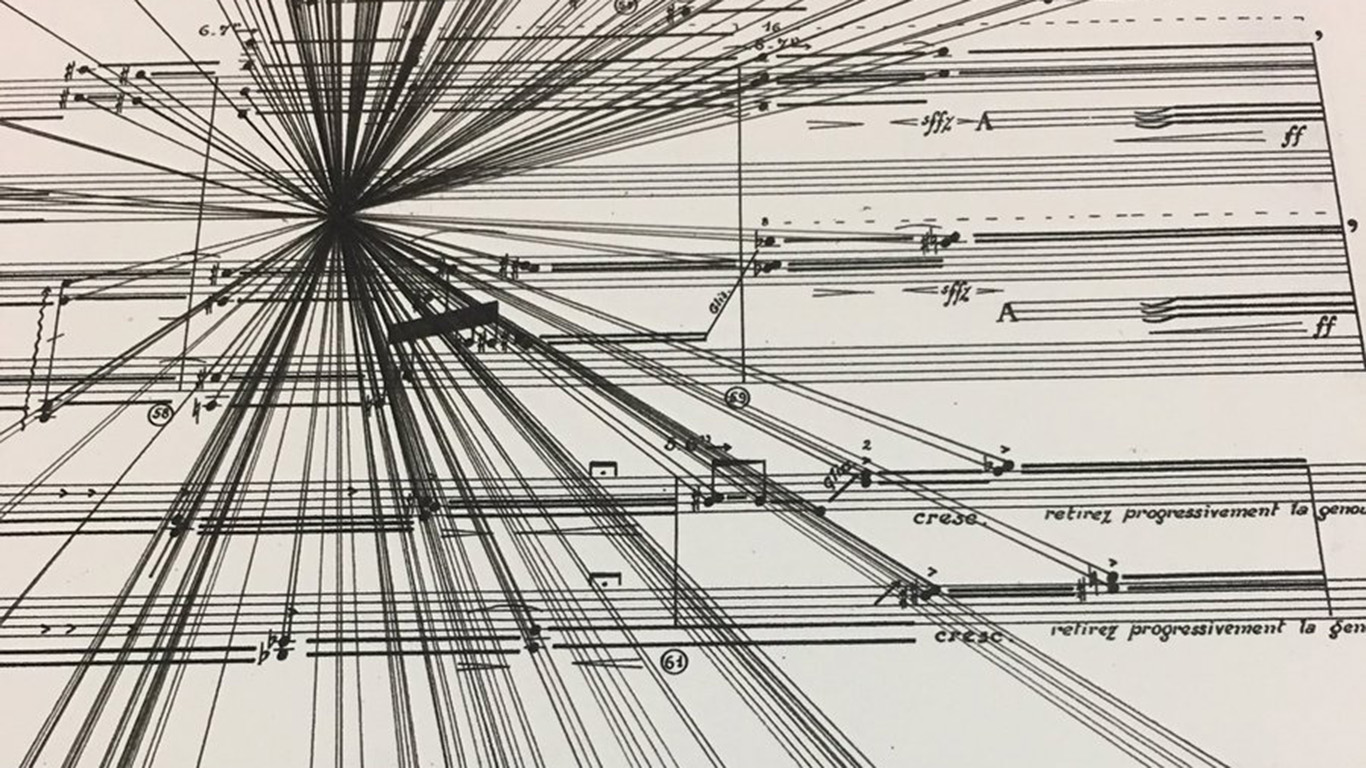

The work, titled Four Proofs and a Conjecture, will encompass five short movements, performed by the Piatti string quartet and based on du Sautoy and Howard’s conversations about different types of mathematical proof. For example, a portion centred on proof by contradiction – which assumes what we want to prove is not true, and then shows that the consequences of this are not possible – needles at a musical interpretation of reductio ad absurdum logic; imagining what the opposite of a piece of music would sound like.

Despite the different languages of the two disciplines, du Sautoy says he found Howard’s description of scoring a piece to be very much like his own process of constructing a proof: “Our working processes are similar in that we may have an overarching idea of where we’re heading, then there’s the careful crafting of each step to get there.

“There were differences, because there’s no ‘truth’ in music. Emily said to me that she could make almost anything work, so it was interesting to look at that tension – why there is an idea of a right and wrong for a mathematician, and that’s not so clear-cut for a composer.”

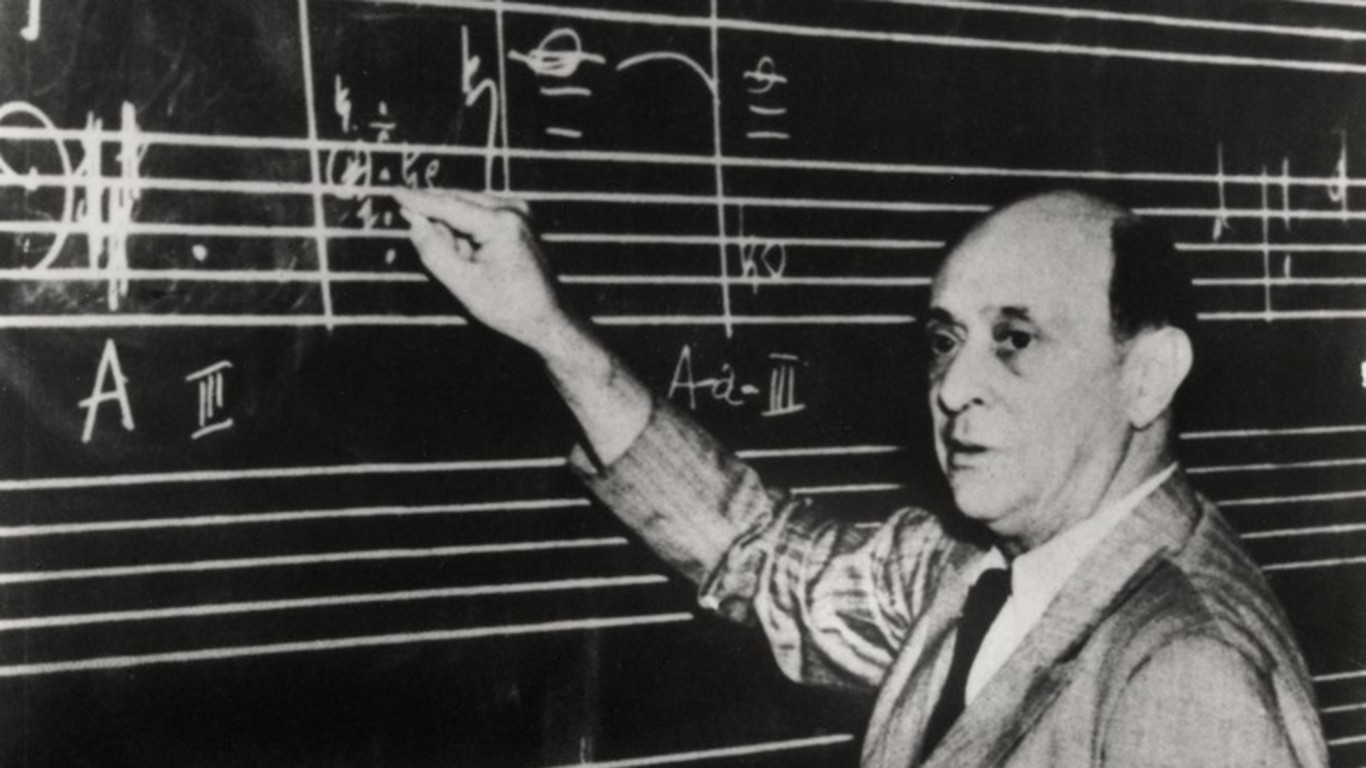

The concept of right and wrong in music is a slippery one. Talk about the “truth” of having a tonal centre and clear harmony, and you’ll quickly come up against the likes of Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, John Cage, Miriam Gideon and Louise Talma, to name a few. What is “right” in music is less an objective certainty and more a subjective mesh of patterns, fixed and broken.

(Above: Arnold Schoenberg)

What du Sautoy wants to emphasise, however, is that maths is also very much about aesthetics, narrative and choice. He tells me that people have the impression maths is trying to construct all the true statements there are about numbers and geometry. But why is Fermat’s Last Theorem celebrated as a great proof in mathematics, he asks, while an equally long and complicated calculation isn’t? “I think what we appreciate is those surprising connections in the mathematical world.”

“It’s very much based on the brain enjoying connection and transformation”

“I think the aesthetic in maths is similar to the aesthetic in music, perhaps more so than any of the other artistic disciplines,” he says. “Because I think it’s very much based on the brain enjoying connection and transformation. It enjoys seeing how one thing is connected to a previous thing, but has changed and is developing.

“I think that’s part of our evolutionary makeup, because if we can spot those patterns and connections, it helps us make predictions about where a thing might be going next. I think the brain is getting these shots of dopamine every time it spots an interesting new pattern.”

The results of du Sautoy and Howard’s conversations will be played on 28 September, as part of New Scientist Live. More details on that here.

Image: Marco Fusinato