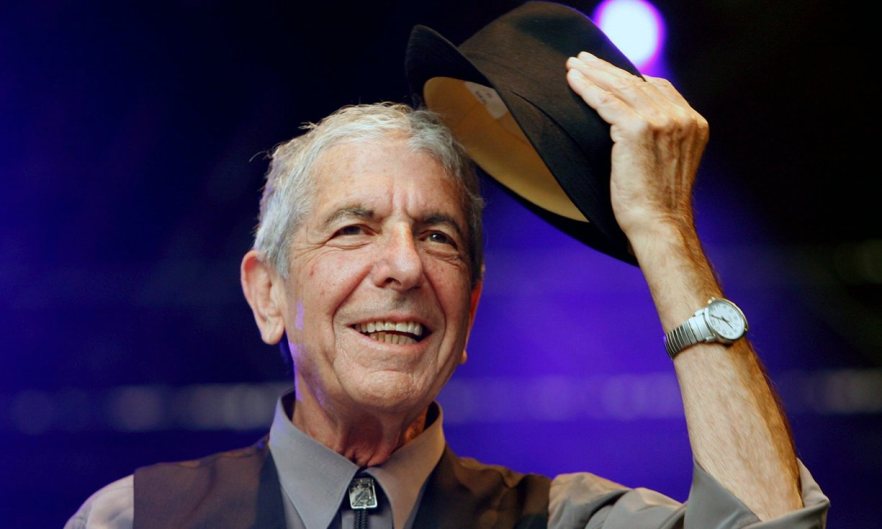

Leonard Cohen – he knew things about life, and if you listened you could learn

The great musician was a man who used songwriting as a way of making sense of a bewildering world

Leonard Cohen was always the grown-up in the room. He was young once, of course, but the world never saw much of the modestly successful poet and novelist from Montreal. He was already 33 — ancient by 60s standards — when he gazed out from the sepia-tinted, photo-booth snapshot on the cover of 1967’s Songs of Leonard Cohen with his shirt, tie and smart side-parting. The face suggested that he’d been around the block a few times; the voice and words confirmed it. The man knew things about life and if, you listened closely, you might learn something.

The truth was that Cohen felt as lost as anybody. What gave his work its uncommon gravitas wasn’t that he knew the answers but that he never stopped looking. He searched for clues in bedrooms and warzones, in Jewish temples and Buddhist retreats, in Europe, Africa, Israel and Cuba. He tried to flush them out with booze and drugs and seduce them with melodies. And whenever he managed to painfully extract some nugget of wisdom, he would cut and polish it like a precious stone before resuming the search. Funny about himself but profoundly serious about his art, he liked to describe his songs as “investigations” into the hidden mechanics of love, sex, war, religion and death – the beautiful and terrifying truths of existence. A Leonard Cohen song is an anchor flung into a churning sea. It has the kind of weight that could save your life.

Young Leonard wrote poems of his own, sang folk songs, and studied (poorly) at McGill University. In 1956 he published his first volume of poetry, Let Us Compare Mythologies, and dedicated it to his father. In a 50th anniversary edition he wrote, with typical self-deprecation: “It’s been downhill ever since.” Around that time he also experienced the “mental violence” of depression for the first time. Decades later, when the worst was behind him, he described it as “the background of your entire life, a background of anguish and anxiety, a sense that nothing goes well, that pleasure is unavailable and all your strategies collapse.”

Leonard Cohen performs Dance Me To The End of Love

Curious and impatient, Cohen moved to New York, London, Israel, Cuba and Greece, where he bought a house on the bohemian idyll of Hydra. More poems. Two novels, one of which a critic called “the most revolting book ever written in Canada”. A few prizes. A truckload of LSD. He talked about writing songs for years before finally knuckling down to it as “an economic solution to the problem of making a living and being a writer”. It was more sociable than poetry, too: he sold his first songs to the folk singer Judy Collins; met Nico and Jim Morrison; jammed with Hendrix. When he wrote, he would play around on the guitar until he felt a catch in his throat. That was when he knew he was on to something. “I certainly never had any musical standard to tyrannise me,” he once said. “I thought that it was something to do with the truth, that if you told the story, that’s what the song was about.”

At the time, Bob Dylan was rock’n’roll’s preeminent poet. Cohen really was a poet but he wasn’t rock’n’roll. Steeped instead in literary discipline, French chanson and Jewish liturgy, his work suggested old-fashioned patience. To Dylan a song was a lump of wet clay to be moulded before it sets fast; to Cohen it was a slab of marble to be chipped into shape with immense dedication and care. Cohen never stopped being a poet or lost his reverence for words. You’ll find some erratic musical choices in his back catalogue but not a single careless line; nothing disposable. Years later, he said he had only one piece of advice for young songwriters: “If you stick with a song long enough it will yield. But long enough is beyond any reasonable duration.” When you sense that a songwriter has spent that long finding the right words, the least you can do is pay attention.

The making of Songs of Leonard Cohen became a maddening slog but these songs – Suzanne; So Long, Marianne; Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye – would make him the so-called “bard of the bedsit”, an intellectual adventurer who looked for glimmers of light in the dark places. As Bono once said: “He finds shades in the blackness that feel like colour.” Robert Altman loved the songs so much he built his 1971 movie McCabe & Mrs Miller around them.

The Nashville-recorded Songs From a Room (1969) was sparser and bleaker than the debut; Songs of Love and Hate (1971) was murder. His depression had grown evil, and infectious. “People were saying I was depressing a generation,” Cohen complained. They called it “music to slit your wrists by”. He was in no state to tour again but he did anyway, and the film-maker Tony Palmer captured it all in his unflinching documentary Bird on a Wire. On stage, Cohen called himself “a broken-down nightingale” who had sold his poetry for celebrity. He revived his sense of self by playing for Israeli troops during the Yom Kippur War and visiting Ethiopia just before the civil war, finding creative inspiration in proximity to violence. “War is wonderful,” he said while promoting New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974). “It’s so economical in terms of gesture and motion. Every single gesture is precise, every effort is at its maximum. Nobody goofs off.” Having compared a tour to a military campaign, he now appeared to be confusing war with a Leonard Cohen tour.

Cohen’s resurgence began with a cheap Casio keyboard he bought in Manhattan, whose plinky presets granted him a new way to write. It underpinned the transitional Various Positions (1984), about which Columbia’s Walter Yetnikoff famously said: “Leonard, we know you’re great, we just don’t know if you’re any good.” The album was largely ignored, although Hallelujah, which took him five years to write and whittle down from more than 80 verses, would eventually become a modern standard, thrilling and moving countless people who had never heard of Leonard Cohen. This ambiguous meditation on spirituality, sex and song unexpectedly grew into his most timeless contribution to the collective songbook.

With I’m Your Man (1988), Cohen found a new voice: both literally, because his baritone went subterranean (“It’s not a strategy,” he said, “I think it’s cigarettes and whiskey”), and figuratively, because his always underrated humour was now too obvious to ignore. “I was born like this,” he rumbled on Tower of Song, “I had no choice, I was born with the gift of a golden voice.” That line always got a laugh in concert. He needed jokes to navigate the album’s hair-raising terrain of fascism, Aids, the Holocaust, sexual betrayal, political defeat and, on Everybody Knows, pessimism elevated to an artform. “These are the final days, this is the darkness, this is the flood,” he told LA Weekly. “The catastrophe has already happened and the question we now face is: What is the appropriate behaviour in a catastrophe?”

Cohen spent five years of the 1990s in the austere environs of the Mount Baldy Zen Center, where he served Joshu Sasaki Roshi, the Japanese monk with whom he had studied for over 20 years. He returned to music with Ten New Songs (2001) and Dear Heather (2004), writing with long-time backing vocalist Sharon Robinson and jazz singer Anjani Thomas. He sounded gentler and more humble, his voice smoky and intimate rather than thick with doom.

Gradually, the floodwaters of depression receded. When losing his savings to his crooked business manager forced him to hit the road again for the first time in 15 years, he became a crowd-pleaser in his own way, finally able to savour an audience’s love. When he cast his benign spell over an arena or, in 2008, a Glastonbury field, he wasn’t bullfighting anymore. On his penultimate two albums, Old Ideas (2012) and Popular Problems (2014), he revisited old territory with a kinder eye and a lighter touch. His investigations were drawing to a close. Then, just weeks ago, came his final album, You Want It Darker, prefaced with an interview with the New Yorker in which he he announced: “I am ready to die. I hope it’s not too uncomfortable. That’s about it for me.” Then he recanted that statement – but it turned out he was telling the truth, as he so often did, one way or another.

On Old Ideas he sang about writing “a manual for living with defeat”, that being the human condition as far as he was concerned. “Nobody has a life that worked out the way they wanted it work out,” he told journalist Mark Ellen in 2007. The role of a good song, he continued, was to share that feeling so that “we feel less isolated and we feel part of the great human chain which is really involved with the recognition of defeat.” For Cohen defeat was the truth of things; the source of all the best jokes; the reason to make art; the crack where the light gets in.

Cohen never talked up his own importance. He often said he was just making the most of the limited talents he had been given and hoping that whatever insights he had gleaned could be useful to the listener. Songwriting was his way of making sense of a bewildering world and dissolving the loneliness.

In 1987, the writer Jon Wilde asked Cohen what he had set out to achieve. “How did I ever get into this racket?” Cohen laughed. “I don’t know! What am I exactly doing in it? I don’t know. I haven’t got a clue. I think it just comes down to nudging the guy next to you and saying, ‘That’s the way, isn’t it?’ They can either agree or not agree. One is continually trying to affirm something with the man in the next seat.”

Photo: Leonard Cohen … ‘How did I ever get into this racket? I don’t know!’ Photograph: Rolf Haid/EPA

via: theguardian