Keaton Music Typewriter

Music typewriters were developed in the 19th century, but it wasn’t until the mid 1900s that they became popular. Musicians usually specialized in using these machines. Several different models were invented, but there were two different concepts that became standard.

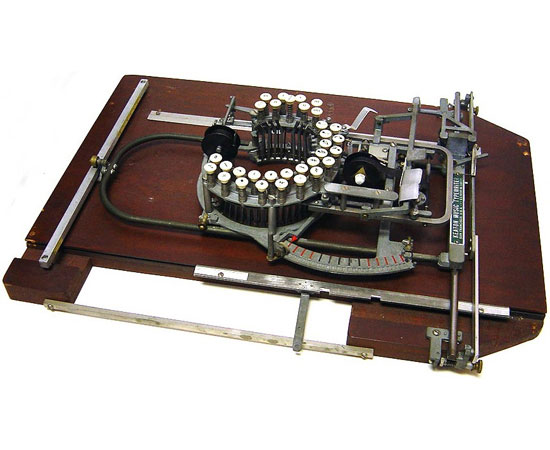

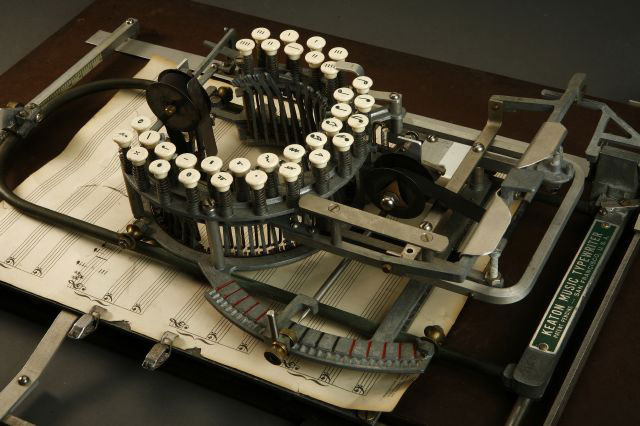

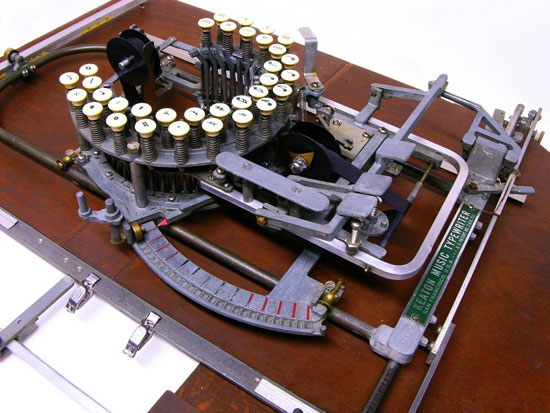

The Keaton Music Typewriter looked very different from a regular typewriter. It had two keyboards, one which was moveable and one stationary. The other models were much like a regular typewriter. They employed musical symbols instead of letters. Staff paper or blank paper was slipped in the carriage and the keys struck. After the music was printed on a music typewriter, the original was photographed or copied to make the extra copies necessary to distribute and sell.

1936/1953

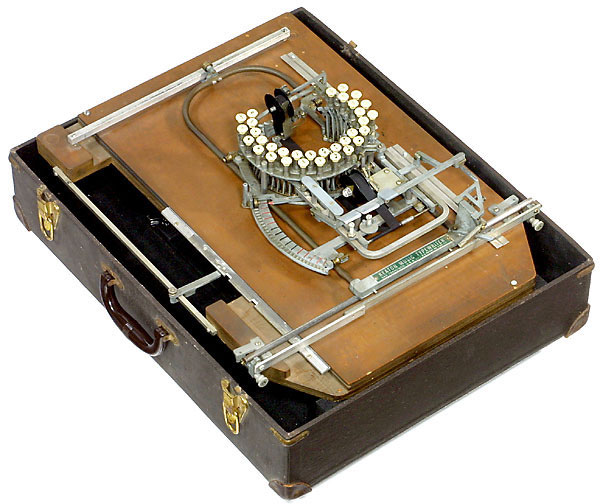

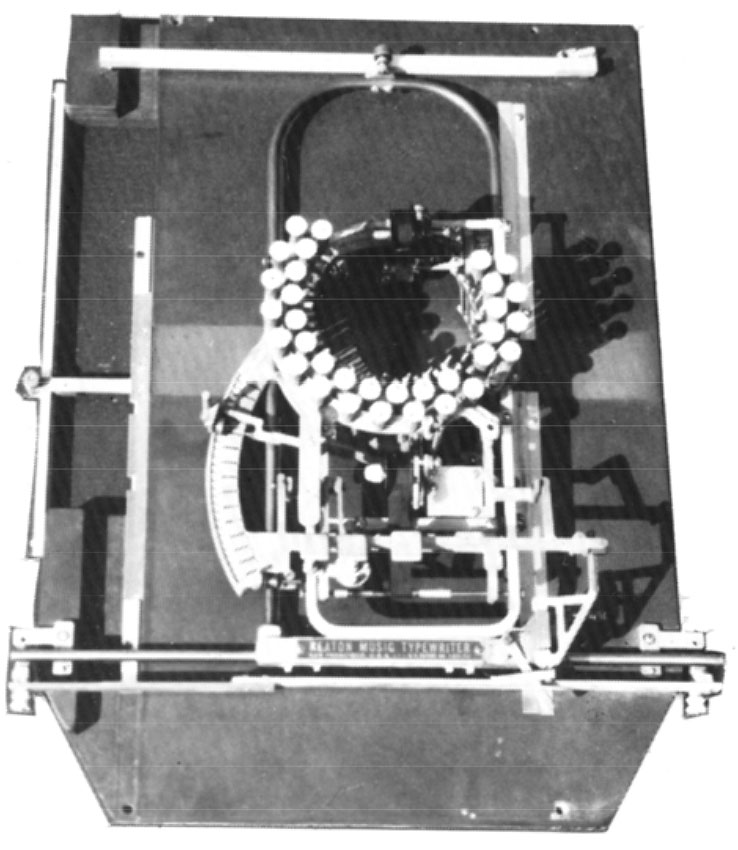

The Keaton Music Typewriter was first patented in 1936 (14 keys) (view 1936 patent) by Robert H. Keaton from San Francisco, California. Another patent was taken out in 1953 (33 keys) (view 1953 patent) which included improvements to the machine. The machine types on a sheet of paper lying flat under the typing mechanism.

There are several Keaton music typewriters thought to be in existence in museums and private collections. It was marketed in the 1950s and sold for around $225. The typewriter made it easier for publishers, educators, and other musicians to produce music copies in quantity. Composers, however, preferred to write the music out by hand.\

From an auction on Live Auctioneers

An image from an auction at Live Auctioneers

Image from auction at Etsy’s

Image from auction at Etsy’s

Image from auction at Etsy’s

Image from auction at Etsy’s

Carnegie Hall Archives Letter

Here is a letter from the Carnegie Hall Archives Department who helped verify the original documentation found with the Keaton Music Typewriter.

Dear Sir,

I have a Keaton Music Typewriter I’d like to have appraised and sold. It was manufactured in San Francisco (might even have been manufactured earlier than ’62 and resold). I have all the supporting documents from 1962, the receipt ($255), manuals, supply list and samples of the sheet music printed with the company name and sales person. This came out of Music Mart, Carnegie Hall, NY NY in 1962 Phil Foote salesperson. Other than two small wood dowlings missing from the base, it is a beautiful piece in perfect condition, in the original case, seemingly untouched for 50 years, when I acquired it. Here is a photo and the Google links.

Mr. XXXX

Response to the letter:

Dear Sir,

Thanks for your e-mail. I wish I could tell you something authoritative about your Keaton Music Typewriter, but unfortunately I never knew this product even existed, and the Google links and Antiques Almanac are more informative than I could ever be on the topic. The only relationship between Music Mart and Carnegie Hall was that of tenant and landlord-apparently, the proprietors of Music Mart rented a studio at Carnegie Hall circa 1959-1962, which accounts for the Carnegie Hall address in the materials you mention.

To give you a bit of quick background: there are approximately 150 rental studios within the Carnegie Hall building; they were not part of the original 1891 complex, but rather were added in the mid-1890s in an effort to provide the hall with extra income (the musical productions alone were not supporting the hall, which in those days was a private enterprise). These studios were rented to painters, sculptors, photographers, music and dance teachers, etc., as well as some arts-related commercial tenants, of which this Music Mart is an example.

Since the Carnegie Hall Archives was not established until 1986, we have very few rental records from the Carnegie Hall Studios, which were basically run as a side enterprise, separate from the musical activities of the hall (many of these records were lost prior to 1986). In fact, Music Mart was not even on our list of known tenants; I found it only by searching the New York Times and finding an advertisement from 1959 (for the sale of an Ampex tape recorder) that lists their Carnegie Hall address, “705 Carnegie Hall,” which would be Studio 705, which means the street address would have been 881 Seventh Avenue (located in the back part of the CH complex).

Regarding an appraisal, I think you would be better served by trying to contact one of the many experts that have written on these devices for some of the various sources you found. Perhaps the editor of the Antiques Almanac could suggest a competent authority. Generally, one of the better indicators of value is the price that similar objects have brought at auction, so the number given in this almanac should give you at least a rough ballpark idea (of course, factors such as condition, date of manufacture, and many, many others will affect this).

Might I ask of you a big favor: would you mind sending us a photocopy (or scan via e-mail?) of the Music Mart document you have that shows the Carnegie Hall location? This would enable us to add Music Mart to our list of tenants with some supporting documentation.Good luck!

All best regards,

MR XXXXXX

Associate Archivist

Carnegie Hall

881 Seventh Avenue

New York, NY 10019

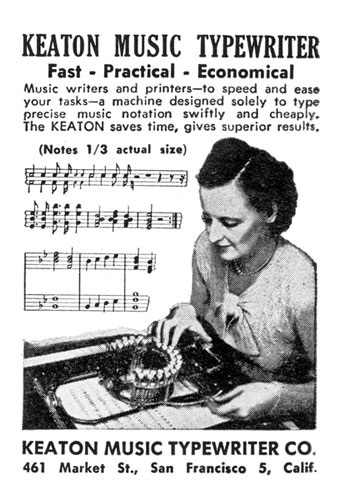

Keaton Music Typewriter ad with the location of the company at 461 Market St., San Francisco, California (see what the location looks like today in Google Maps)

This ad, as in the previous ad, states that it’s Fast, Practical and Economical

Using the Keaton Music Typewriter

How the Keaton Typewriter Works

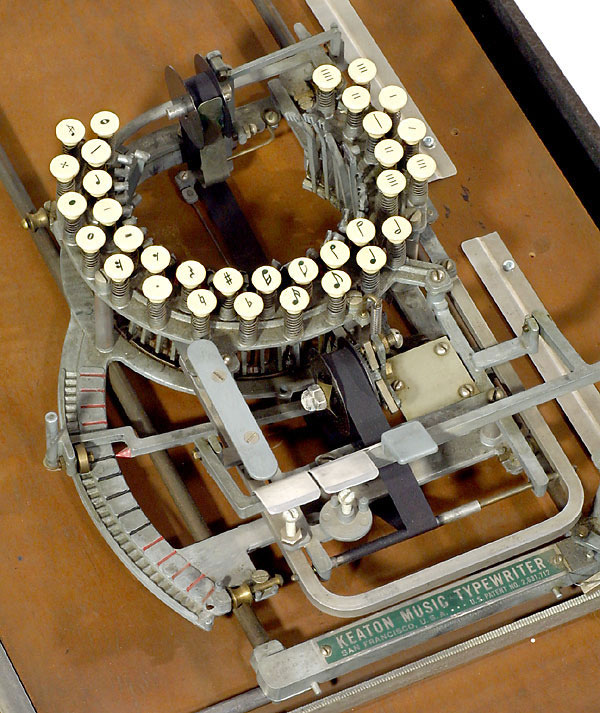

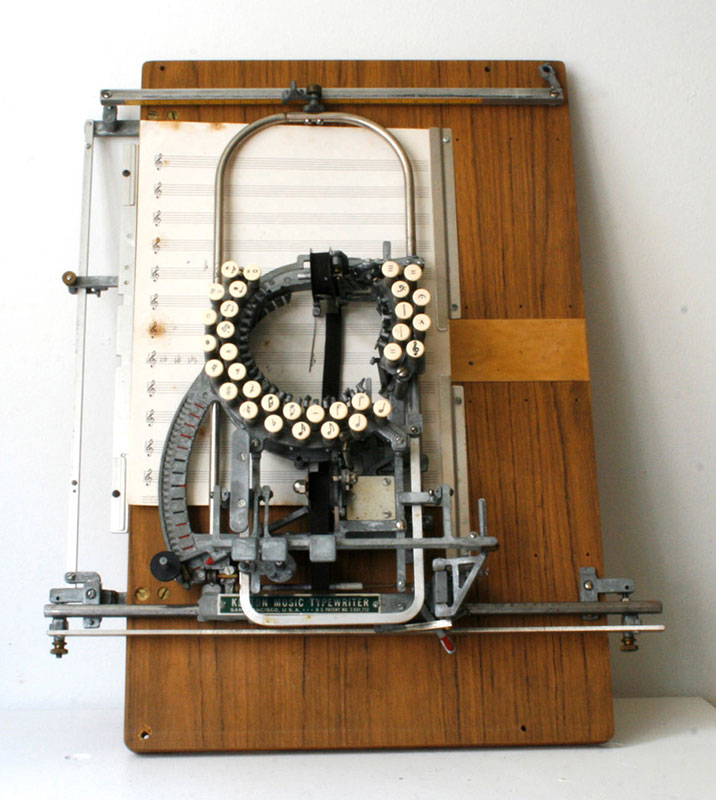

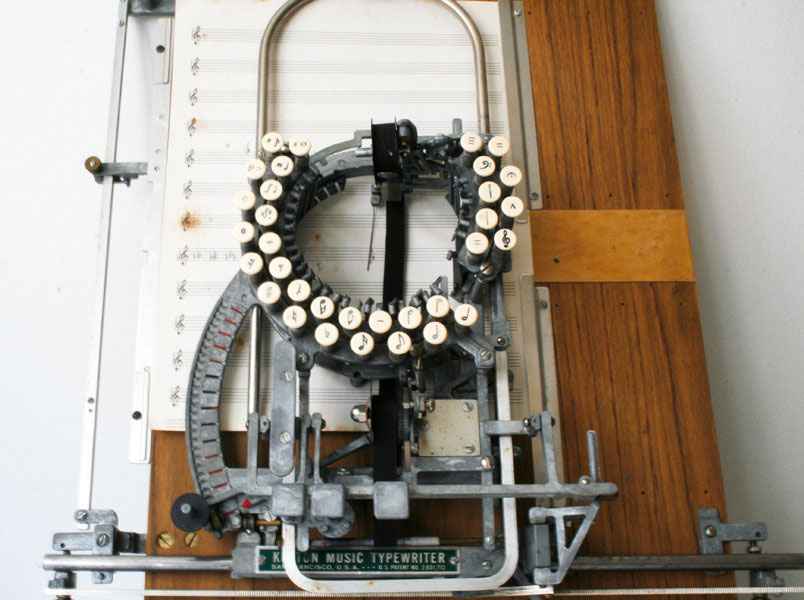

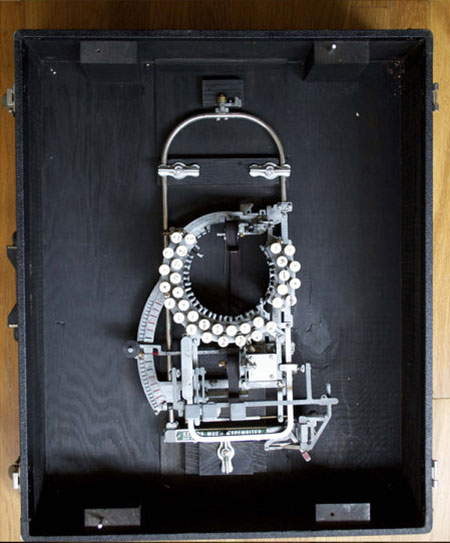

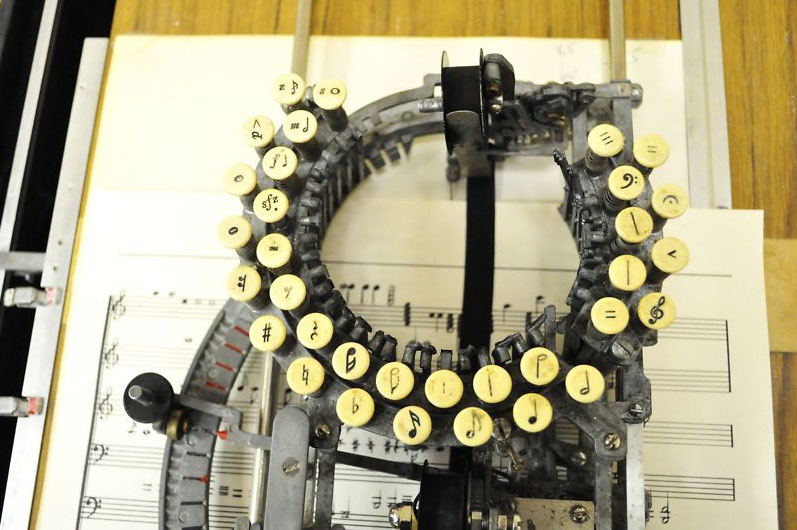

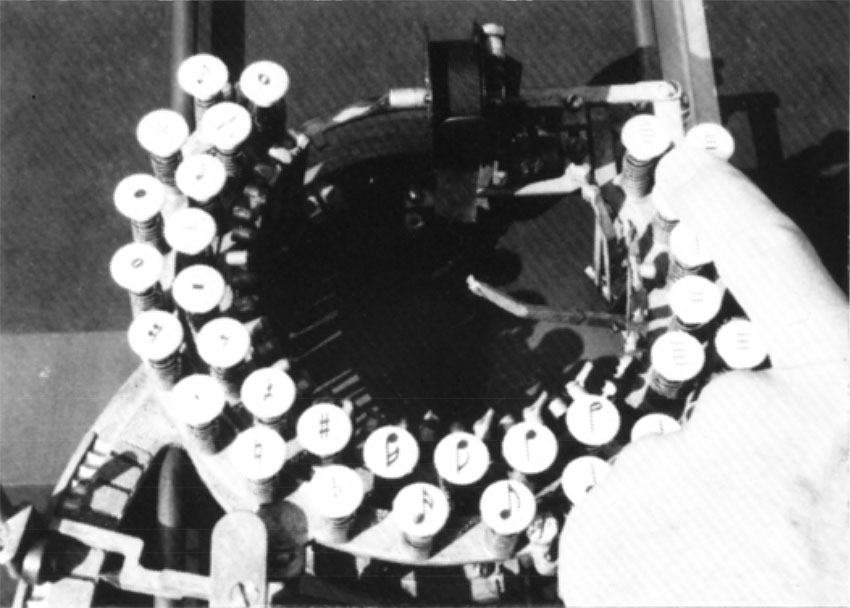

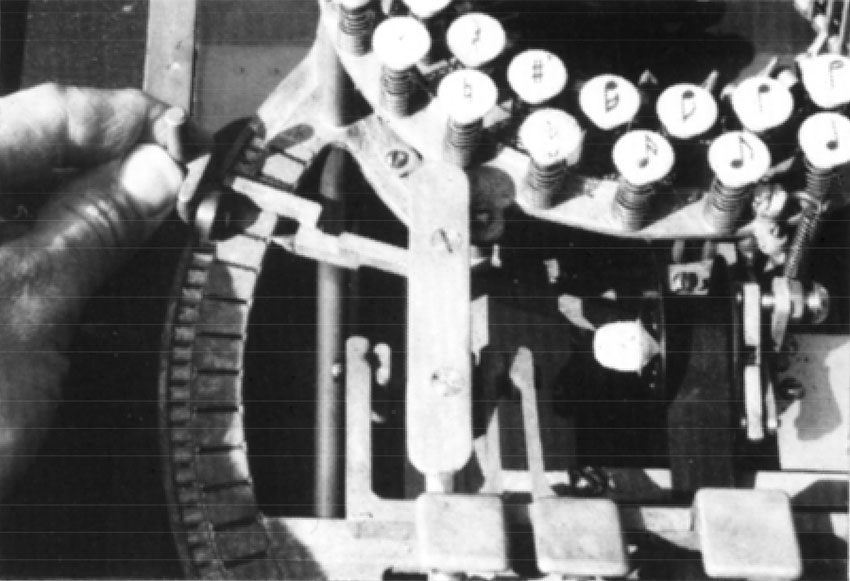

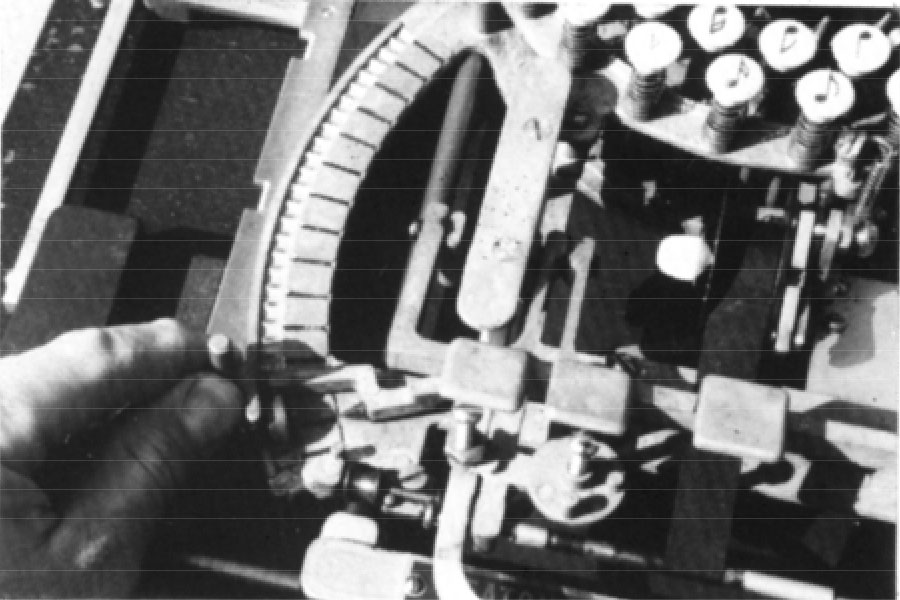

The typewriter has a handle, called the scale shift handle, to the left of the circular keyboard, which moves over a notched metal arc. This moves a long needle, adjacent to the ribbon, which indicates where the next symbol is to be printed. The machine contains two keyboards – one smaller, stationary keyboard and the other larger, moveable keyboard which is moved by the scale shift handle. The smaller keyboard contains bar lines and ledger lines which remain in a fixed position to the staff paper. (Preprinted staff paper is used with the Keaton typewriter.) The larger part of the keyboard contains the notes, rests, sharps, flats, and other musical symbols.

There are three spacing keys used for different purposes such as adding spaces for accidentals, grace notes, or dots. The keys are pressed straight down onto the staff paper where the long needle indicates the position. A printing ribbon runs under the symbols which allow for the printing to take place.

Keaton Music Typewriter

Keaton Music Typewriter

Keaton Music Typewriter

Keaton Music Typewriter

Keaton Music Typewriter

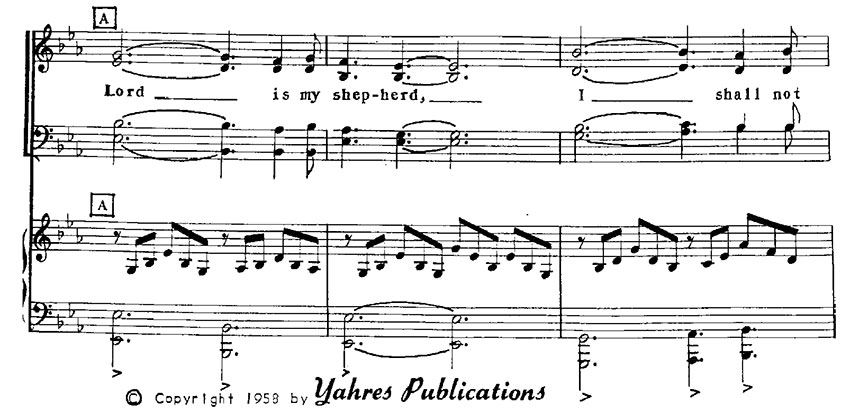

Sample of Keaton’s work, as used by Yahres Publications, Coraopolis, PA

Article from ETCetera Magazine

The following article is taken from ETCetra Magazine. The images herein are taken from the magazine as well.

The Keaton Music Typewriter by Darryl Rehr

The current literature on music typewriters is sketchy at best. A brief survey will reveal that most such machines were adapted from existing typewriters, and none seems to have made a large market impact.

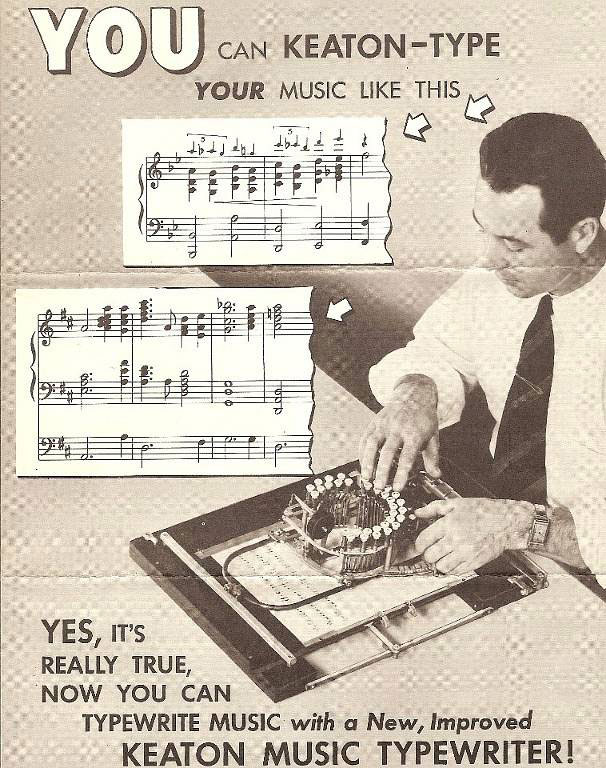

Almost totally absent from typewriter history references is information on perhaps the most-interesting music machine of them all, the spectacular Keaton Music Typewriter made in San Francisco during the 1950’s.

Anyone familiar with the recent Smithsonian magazine article on typewriters will remember the exquisite color photo of this machine, with its round keyboard and flat platen. In fact, the Keaton uses a downstroke circular keyboard, much like such typewriter exotica as the Crary, Daw & Tait or the Crown keyboard machine, items at thepinnacleof rarity in the field.

The Keaton Music Typewriter was first patented in 1936 by Robert H. Keaton of San Francisco, with improvements made in a second patent granted in 1953. In hispatent, Keaton set out the design goals of his invention, which could easily be applied to any music typewriter. Among his points:

“…in view of the fact that musical characters are written on a staff comprising five closely spaced staff lines and four spaces between the lines, it is essential that provision be made to print the musical notes and characters in exact position upon the paper.

“…to provide means to indicate the exact typing locus on the paper whereat the next musical character will be typed.

“…to provide… a novel keyboard arrangement whereby one keyboard is adapted to type one class of music characters such as bar lines and ledger lines, which, when repeated, always appear in the same relative spaced positions with respect to the [staff] lines… and a second keyboard adapted to type another class of musical characters, such as the notes, rest signs and sharp and flat signs etc., which may, when repeated, appear in various spaced positions with respect to the [staff] lines.”

Let’s look at the machine to see how Keaton accomplished his goals, first, a mechanism for precisely locating the notes/characters on the page. To the left of the keyboard is a handle which moves over a notched metal arc. Keaton calls these the Scale Shift Handle and the Scale Shift Indicator. Each notch moves the printing point up or down exactly 1/24″ of an inch. Instructions for the machine specify use of staff paper with lines printed 1/12″ apart, so each notch of the Scale Shift Indicator allows printing one musical step (a line or space) up or down. There’s more to this up/down motion, but we’ll get to that later.

Keaton Music Typewriter ser. #3184

Keaton’s second point was to give the user an exact indication of where the next character would be typed. The reason is obvious. Music writers had to be able to put their notes at exact positions on the staff. Keaton’s solution was very simple: a long needle, adjacent to the ribbon, which left no doubt about the next printing position.

Keaton keyboard showing downstroke action

The third principle is Keaton’s mention of two keyboards. This sounds odd at first, since the machine does seem to have a single keyboard unit, but a close examination reveals something else. In the image above you’ll see the Scale Shift Handle at the very top of the Scale Shift Indicator. In this position, the keyboard appears as it does in the image below, a single, circular unit.

Scale Shift Handle in uppermost position

In the image below, the Scale Shift Handle has moved to the lowest point on the Scale Shift Indicator.

Scale Shift Handle in the lowest position

In this position, the keyboard appears as in the image below. You can readily see that the keyboard seems to have split into two pieces.The larger portion has moved down along with the Scale Shift Handle, while the smaller portion has remained in its original position.

Looking closely at the keys, you’ll see the reason.The small part of the keyboard includes the vertical bar line and the groups of little horizontal lines needed for typing notes above or below the five lines of the printed staff. AsKeaton says, these characters must remain in a fixed position relative to the staff paper.

The larger part of the keyboard contains all of the actual notes, rests, sharps and flats which must be free to move up or down in relation to the staff lines. So, in essence, there are indeed two keyboards, one fixed, one movable.

The two parts of the keyboard are very apparent

Another interesting mechanical feature on the Keaton is its space key, or actually, its three space keys. Unlike alphabetic typewriters, this machine does not automatically space as each character is typed. Instead there are three space keys, allowing the user to move the type head different numbers of units for different purposes.The left space key is 2 units, used for sharps/flats, grace notes, dots after notes, cluster chords, notes in tight formation, etc. The middle space key is 3 units, used for notes in close order, and before and after bar lines. The right space key is adjustable to 4, 5, or 6 units, used for chords and more widely spaced notes. Each “unit” is 1/20″. A similar arrangement was used in the IBM Executive typewriter, which wrote proportionally spaced characters. It, too, had different space keys for different spacing.

It is very difficult to judge the commercial success of the Keaton machine. Even if it sold well, the nature of such a product gives it a very limited market. I know of about 6 surviving examples in museums and private collections. We do know that it was being actively marketed in the mid-50’s, and have one advertisement from that period (our cover illustration). This comes from a packet of literature uncovered by Larry Wilhelm with the example of the machine he discovered. The literature contains correspondence between the Keaton Music Typewriter Co. and Samuel C. Yahres of Coraopolis, PA dated October, ’54 through February, ’58 in which Yahres purchased a machine (price $225), made payments and later ordered additional supplies (staff paper and duplicator masters).

Mr. Yahres was head of Yahres Publications, a music publishing house, and tells ETCetera the machine was intended for use by publishers, educators and others who produced musical copy in quantity. It provided a shortcut to the cumbersome technique of hand-engraving music on lithographic stones, as was the practice. He himself found it very useful (a sample of his copy is shown), but says composers would have found it too slow, most preferring to dash out their compositions by hand.

This characterization shows that the Keaton machine was very much a specialty product, with very limited use. This certainly accounts for its rarity today, and adds to a collector’s delight when one is discovered.