How to Teach Art to Kids, According to Mark Rothko

βy Sarah Gottesman

If you’ve ever seen Mark Rothko’s paintings—large canvases filled with fields of atmospheric color—and thought, “a child could do this,” you’ve paid the Abstract Expressionist a compliment.

Rothko greatly admired children’s art, praising the freshness, authenticity, and emotional intensity of their creations. And he knew children’s art well, working as an art teacher for over 20 years at the Brooklyn Jewish Center. To his students—kindergarteners through 8th graders—Rothko wasn’t an avant-garde visionary or burgeoning art star, he was “Rothkie.” “A big bear of a man, the friendliest, nicest, warmest member of the entire school,” his former student Martin Lukashok once recalled.

Rothko was a thought leader in the field of children’s art education. He published an essay on the topic (“New Training for Future Artists and Art Lovers”) in 1934, which he hoped to follow up with a book. Though he never completed the project, he left behind 49 sheets of notes, known as “The Scribble Book,” which detailed his progressive pedagogy—and from which we’ve taken five lessons that Rothko wanted all art teachers to know.

Lesson #1: Show your students that art is a universal form of expression, as elemental as speaking or singing

Mark Rothko Heads, 1941-1942 Washburn Gallery

Rothko taught that everyone can make art—even those without innate talent or professional training. According to the painter, art is an essential part of the human experience. And just as kids can quickly pick up stories or songs, they can easily turn their observations and imaginings into art. (Similarly, he believed, taking away a child’s access to artmaking could be as harmful as stunting their ability to learn language.)

For Rothko, art was all about expression—transforming one’s emotions into visual experiences that everyone can understand. And kids do this naturally. “These children have ideas, often fine ones, and they express them vividly and beautifully, so that they make us feel what they feel,” he writes. “Hence their efforts are intrinsically works of art.”

Lesson #2: Beware of suppressing a child’s creativity with academic training

Mark Rothko Untitled, 1948 Fondation Beyeler

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1947, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

As Rothko saw it, a child’s expressiveness is fragile. When art teachers assign projects with strict parameters or emphasize technical perfection, this natural creativity can quickly turn to conformity. “The fact that one usually begins with drawing is already academic,” Rothko explains. “We start with color.”

To protect his students’ creative freedom, Rothko followed a simple teaching method. When children entered his art room, all of their working materials—from brushes to clay—were already set up, ready for them to select and employ in free-form creations. No assignments needed.

“Unconscious of any difficulties, they chop their way and surmount obstacles that might turn an adult grey, and presto!” Rothko describes. “Soon their ideas become visible in a clearly intelligent form.” With this flexibility, his students developed their own unique artistic styles, from the detail-oriented to the wildly expressive. And for Rothko, the ability to channel one’s interior world into art was much more valuable than the mastery of academic techniques. “There is no such thing as good painting about nothing,” he once wrote.

Lesson #3: Stage exhibitions of your students’ works to encourage their self-confidence

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1954

Yale University Art Gallery

Mark Rothko, Number 18, 1951, Munson Williams Proctor Arts Institute, Utica

“I was never good at art,” recalled Rothko’s former student Gerald Phillips. “But he…made you feel that you were really producing something important, something good.”

For Rothko, an art teacher’s premier responsibility was to inspire children’s self-confidence. To do this, he organized public exhibitions of his students’ works across New York City, including a show of 150 pieces at the Brooklyn Museum in 1934. And when Rothko had his first solo exhibition at the Portland Art Museum a year earlier, he brought his students’ works along with him and exhibited them next to his own.

These exhibitions gave Rothko’s students a newfound excitement about their work, while educating the public about the potential of children’s art. “It is significant,” Rothko writes, “that dozens of artists viewed this exhibition [of student works at the Brooklyn Museum] and were amazed and stirred by it.” Rothko wanted critics to see that fine art only requires emotional intensity to be successful.

Lesson #4: Introduce art history with modern art (not the Old Masters)

Milton Avery Walker by the Sea, 1961, American Federation of Arts

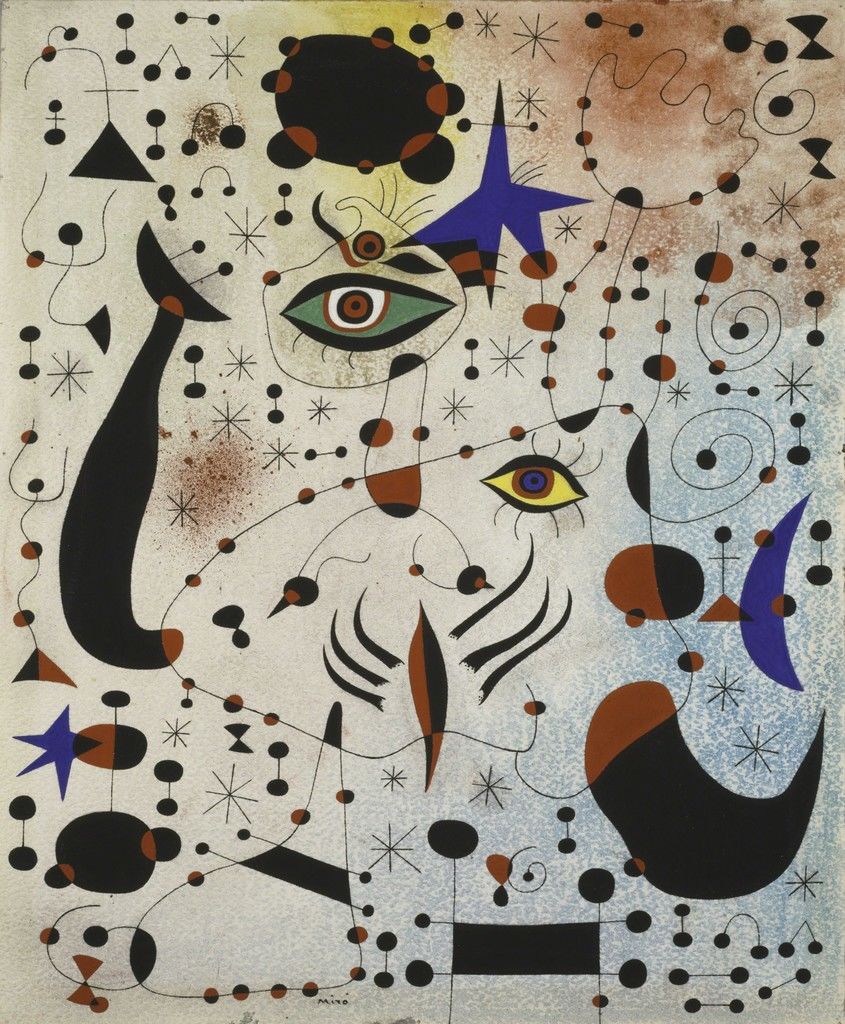

Joan Miró, Ciphers and Constellations in Love with a Woman, 1941, Art Institute of Chicago

When teaching young students about art history, where do you start? For Rothko, the answer was clear: Modernism.

With 20th-century art, children can learn from works that are similar to their own, whether through the paintings of Henri Matisse, Milton Avery, or Pablo Picasso. These iconic artists sought pure, personal forms of visual expression, free from the technical standards of the past. “[Modern art] has not been obscured by style and tradition as that of the old masters,” Rothko explains. “It is therefore particularly useful to us…to serve as an interpreter to establish the relationship between the child and the stream of art.”

But while exposure to modern art can help boost children’s confidence and creativity, it shouldn’t interfere with the development of a unique style. Rothko discouraged his students from mimicking museum works as well as his own painting practice. “Very often the work of the children is simply a primitive rendition of the creative ends of the artist teacher,” he warns. “Therefore it has the appearance of child art, but loses the basic creative outlet for the child himself.”

Lesson #5: Work to cultivate creative thinkers, not professional artists

Mark Rothko

Untitled (Black and Orange on Red), 1962

Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art

Mark Rothko

No. 15, 1957

“Abstract Expressionism” at Royal Academy of Arts, London

In addition to fanning students’ creative instincts, great art teachers can help students become more self-aware, empathetic, and collaborative—and this generates better citizens in the long run, Rothko believed. At the Brooklyn Jewish Center, he hardly cared whether his students would go on to pursue careers in the arts. Instead, Rothko focused on cultivating in his students a deep appreciation for artistic expression.

“Most of these children will probably lose their imaginativeness and vivacity as they mature,” he wrote. “But a few will not. And it is hoped that in their cases, the experience of eight years [in my classroom] will not be forgotten and they will continue to find the same beauty about them. As to the others, it is hoped, that their experience will help them to revive their own early artistic pleasures in the work of others.”

And, in turn, Rothko’s own creativity was revived by his students’ unabashed expressiveness. When the artist began teaching, his works were still somewhat figurative, depicting street scenes, landscapes, portraits, and interiors with loose brushwork. Upon retirement, his style had transformed to complete abstraction, taking the form of vivid, color-filled canvases that he hoped would intuitively resonate with adults and children alike.