How a school in Bradford is beating the odds with music

by Dougal Shaw

A primary school in a deprived part of Bradford has gone from failing school to success story. The transformation, it says, is down to a decision to rebuild its curriculum around music.

Adyan, who is nearly five, can barely stand still in the school’s music room. His mother, Rabia, is growing impatient.

“Come on: one, two, three, start,” she says. “Please, sing.”

But Adyan doesn’t. He’s scampered off to another part of the room, shouting.

He’s meant to be showing me that he can recite the alphabet while playing a simple tune on the piano – a big achievement for a child who could barely speak English when he first arrived at school.

“Adyan is a hyperactive child and he has traces of autism,” explains Rabia. “Sometimes it can be really hard to understand him. Being a mummy I always said, ‘Yes, I can do it’. But I don’t understand it. The music is unlocking some of that communication.”

At last, with no warning, Adyan rushes to the piano and launches into his alphabetical journey. Each cautious press of the piano key seems to give him the confidence to sing the next letter.

There’s a wobble around “m, n, o, p…”, when he begins to shout the letters in a distracted way. But then the soft piano sounds seem to lull him back into a state of concentration.

At “z” a beaming Rabia bursts into applause, with Jimmy Rotheram, the school’s music coordinator, joining in.

“He gave him courage,” says Rabia, pointing at Rotheram, who is standing by her side. “He didn’t let him go.

“Give Mr. Rotheram a high-five, Adyan.”

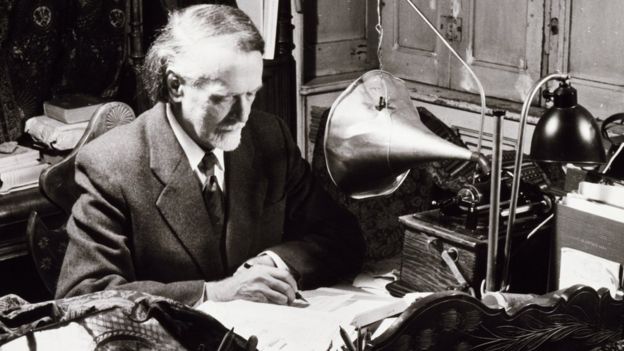

Jimmy Rotheram is Feversham Primary’s first music coordinator

Jimmy Rotheram is Feversham Primary’s first music coordinator

Jimmy Rotheram is a man full of nervous energy, who exudes a passion for music.

When not teaching, he plays funk and soul on Yorkshire’s live music scene.

In his late 20s and 30s he taught music in secondary schools and colleges. But he left the profession feeling overworked and underpaid, hoping instead to be a full-time musician.

When he couldn’t make ends meet, he began supply teaching again, but this time at primary schools, including this one, Feversham Primary Academy. He found the younger children’s natural enthusiasm fully ignited his passion for teaching music.

“I always use the analogy of swimming,” he says. “If you drop a young baby into the water they will just swim naturally. If you leave it too long they forget how to swim.”

He arrived at Feversham Primary at just the right time. In 2013 a new headmaster was looking to make radical changes.

Government inspectors had put Feversham Primary in special measures. This means they thought the school was offering an unacceptable standard of education and needed new leadership. In November 2012 it had become an Academy, run by a trust.

Headmaster Naveed Idrees was keen to bring a new ethos to the failing school

Headmaster Naveed Idrees was keen to bring a new ethos to the failing school

“The children were disengaged,” explains current headmaster Naveed Idrees. “The curriculum was unstimulating, behaviour was a massive issue, parents were completely switched off. We deserved to be where we were.”

Meeting government examination targets would be a challenge for any school in Feversham Primary’s position. More than 98% of its pupils, including Adyan, speak English as an additional language, the vast majority being from a Pakistani background.

It’s also in a catchment area that, despite a nice suburban veneer, is dealing with high levels of poverty and crime.

But six years on, the school inspectors rate the school very differently. According to performance tables, it is in the top 10% of schools in England when it comes to progressing children’s learning in core subjects like maths and English. For the eldest pupils at the school who have come through the system, their progress in reading and maths places them in the top 2% and 1% respectively in England.

So how did it achieve this remarkable turnaround?

The vast majority of pupils at Feversham Primary Academy speak English as an “additional language”

The vast majority of pupils at Feversham Primary Academy speak English as an “additional language”

It is a myth that English, maths and science are the most important subjects, according to Idrees.

“What we discovered is that children need to be engaged not just at the level of the mind and body, but also the level of the soul.”

The school took a gamble by focusing its resources on music, creating a full-time job for Rotheram in a brand new role, that of music coordinator. It was partly able to fund this through pupil premium funding, the extra money schools are given to support their children from the poorest backgrounds.

It also appointed new specialists in drama, science and design technology, but government inspectors and the school’s own headmaster highlight music as the catalyst that changed the school.

“When I first started supply teaching, music would often not be taught here at all,” recalls Rotheram.

“I don’t blame teachers for this, because it’s very hard if you’ve not been trained to do something.”

In his experience, music often falls to the bottom of the pile in schools. It is not a core subject in England’s education system, unlike maths, English or science. There’s no minimum amount of time that schools are obliged to devote to it – there are just a few general targets for musical competence.

“It’s just a tick-box exercise. It might be just putting a CD on and writing about Beethoven’s trip to the countryside,” says Rotheram.

WATCH: The lessons are designed so children actively engage with music

Pupils at Feversham now have three hours of music timetabled into their school week. In fact many pupils are doing up to eight hours a week, explains Rotheram, by choosing to do things like choirs and clubs. This is a much bigger commitment to music than you would get in most state schools.

The music classes built into the school timetable are all highly practical and active – a far cry from children passively listening to a CD.

“My number one rule is that it should always be a joy, never a torture,” says Rotheram.

For the younger pupils, his classes take on a party atmosphere. Children charge around the room, with Rotheram directing the action from behind the piano.

“I like it because it is very energetic and entertaining,” volunteers an exhausted year one student.

Other exercises like “Jack in the Box” are like memory games, with children taking it in turn to sing back short musical phrases.

Older children play more complex musical games, as well as sight-reading songs.

Pupils are encouraged to perform at a weekly assemble

Pupils are encouraged to perform at a weekly assemble

Though Rotheram’s lessons seem exuberant and party-like, they are actually underpinned by a carefully thought-out musical method that is specially designed for children.

It is known as the “Kodaly method”, after the man who invented it, Hungarian musician Zoltan Kodaly (1882-1967).

A celebrated classical composer, he also had a keen interest in folk music and a passion for unlocking children’s musical potential.

After much research, he devised a programme for teaching children music that used popular Hungarian folk songs. It was based primarily around singing, so no expensive musical instruments were required.

DEA / A. DAGLI ORTI-Zoltan Kodaly worked with the government in the 1950s to spread his musical method in Hungary

The accessibility of the method appealed to the Communist Party and from the 1950s it was the standard way to teach music in Hungarian schools. It remained so until the fall of Communism in the late 1980s.

Rotheram has been training himself up in the Kodaly method since joining Feversham, taking extra classes during weekends and holidays, to refine what he teaches at the school. He’s attracted to the idea that every child has musical potential, whatever their social background.

“It’s brilliant here because I’ve got the chance to nurture children from the parents and babies’ group all the way up to age 11. That’s phenomenal, you can really develop every step of the way,” he says.

The school has taken measures to ensure musical exercises even become part of playtime

The school has taken measures to ensure musical exercises even become part of playtime

A conscious decision was made to let music permeate throughout the school. At playtime you can hear the echoes of Rotheram’s lessons as older children, appointed as playground leaders, get younger pupils to repeat the musical exercises they learned in class.

There is also a musical assembly every week where pupils perform, and guest musicians too.

These events have been vital in getting parents on board, many of whom were sceptical of the musical revolution. Some parents resisted on religious grounds, complaining to the headmaster.

“When we first started out we’d do concerts and we’d get one or two parents turning up. And they’d be on their phones the whole time, not clapping when the children finished singing,” recalls Rotheram.

“So we started getting Muslim musicians to come in to the school, to show children you can be a Muslim and be a good musician. I managed to get Ahmad Hussain, one of the best Nasheed singers in the world.

IQRA-Popular Nasheed singer Ahmad Hussain, a star on YouTube, visits the school

Nasheeds are Islamic songs and Jimmy has incorporated some of these into his lessons, as well as African and East European folk songs, to appeal to his pupils – and their parents.

But can this musical revolution explain the school’s improved academic results, which have seen it shoot up the performance tables?

Someone with a keen interest in this is Dr Katie Overy, an academic at the University of Edinburgh.

She has been studying the impact of music on areas like education and therapy for 25 years and has been in contact with Rotheram.

“There are an increasing number of studies that have shown that music can benefit language development, perceptual and social skills,” she says.

Music can develop precise timing skills and this might benefit learning in other subjects, says Overy.

Rotheram says that his pupils have enhanced concentration and memory skills.

However, there is no scientifically proven connection between music and improved academic performance. And of course, the changing fortunes of a school can be down to complex reasons.

Some pupils will do up to eight hours of music each week

Some pupils will do up to eight hours of music each week

Though he acknowledges this, headmaster Idrees still believes music is the key to his school’s success and wants others to take notice.

There is pressure on schools to avoid putting resources into music and arts, he explains, in case it negatively affects exam results in core subjects.

“What I can say to headteachers is that music and arts are the bedrock of educational success. Your results will go up, not down.”

For Rotheram, it doesn’t seem to be school test scores that motivate him. It’s the smaller, more personal victories that take place in his music room. Like when a struggling child, such as Adyan, finds the strength through music to complete the alphabet, bringing tears of joy to his mother.