Big Wolf & Little Wolf: A Tender Tale of Loneliness, Belonging, and How Friendship Transforms Us

A subtle meditation on the meaning of solidarity, the relationship between the ego and the capacity for love, and the little tendrils of care that become the armature of friendship.

We spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins. There is a strange and sorrowful loneliness to this, to being a creature that carries its fragile sense of self in a bag of skin on an endless pilgrimage to some promised land of belonging. We are willing to erect many defenses to hedge against that loneliness and fortress our fragility. But every once in a while, we encounter another such creature who reminds us with the sweetness of persistent yet undemanding affection that we need not walk alone.

Such a reminder radiates with uncommon tenderness from Big Wolf & Little Wolf (public library) by French author Nadine Brun-Cosme, illustrated by the always magical Olivier Tallec and translated by publisher Claudia Zoe Bedrick, the visionary founder of Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion. With great subtlety and sensitivity, the story invites a meditation on loneliness, the meaning of solidarity, the relationship between the ego and the capacity for love, and the little tendrils of care that become the armature of friendship.

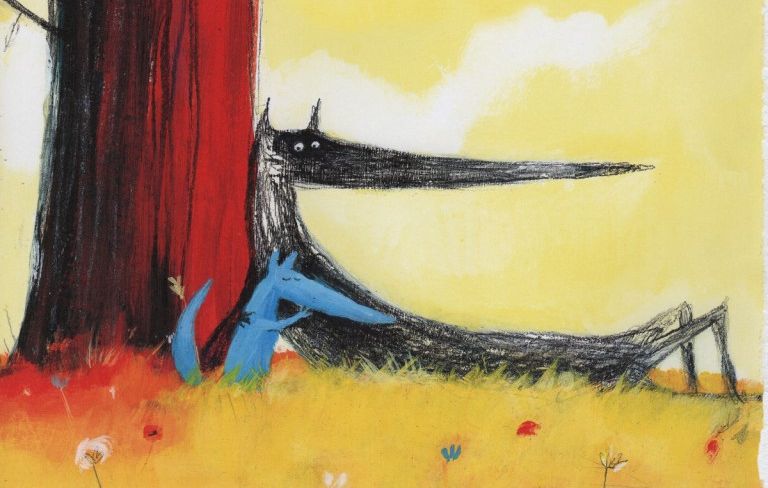

We meet Big Wolf during one of his customary afternoon stretches under a tree he has long considered his own, atop a hill he has claimed for himself. But this is no ordinary day — Big Wolf spots a new presence perched on the horizon, a tiny blue figure, “no bigger than a dot.” With that all too human tendency to project onto the unknown our innermost fears, Big Wolf is chilled by the terrifying possibility that the newcomer might be bigger than he is.

But as the newcomer approaches, he turns out to be Little Wolf.

Big Wolf saw that he was small and felt reassured. He let Little Wolf climb right up to his tree.

“It is a sign of great inner insecurity to be hostile to the unfamiliar,” Anaïs Nin wrote, and it is precisely the stark contrast between Big Wolf’s towering stature and his vulnerable insecurity that lends the story its loveliness and profundity.

At first, the two wolves observe one another silently out of the corner of their eyes. His fear cooled by the smallness and timidity of his visitor, Big Wolf begins to regard him with unsuspicious curiosity that slowly warms into cautious affection. We watch Big Wolf as he learns, with equal parts habitual resistance and sincerity of self-transcendence, a new habit of heart and a wholly novel vocabulary of being.

Night came.

Little Wolf stayed.

Big Wolf thought that Little Wolf went a bit too far.

After all, it had always been his tree.When Big Wolf went to bed, Little Wolf went to bed too.

When Big Wolf saw that Little Wolf was shivering at the tip of his nose, he pushed a teeny tiny corner of his leaf blanket closer to him.“That is certainly enough for such a little wolf,” he thought.

When morning breaks, Big Wolf goes about his daily routine and climbs up his tree to do his exercises, at first alarmed, then amused, and finally — perhaps, perhaps — endeared that Little Wolf follows him instead of leaving.

Once again, Big Wolf at first defaults to that small insecure place, fearing that Little Wolf might outclimb him. But the newcomer struggles, exhaling a tiny “Ouch” as he thuds to the ground on his first attempt before making it up the tree, leaving Big Wolf both unthreatened and impressed with the little one’s quiet courage.

Silently, Little Wolf mirrors Big Wolf’s exercises. Silently, he follows him back down. On the descent, Big Wolf picks his usual fruit for breakfast, but, seeing as Little Wolf isn’t picking any, grabs a few more than usual. Silently, he pushes a modest plate to Little Wolf, who eats it just as silently. The eyes and the body language of the wolves emanate universes of emotion in Tallec’s spare, wonderfully expressive pencil and gouache illustrations.

When Big Wolf goes for his daily walk, he peers at his tree from the bottom of the hill and sees Little Wolf still stationed there, sitting quietly.

Big Wolf smiled. Little Wolf was small.

Big Wolf crossed the big field of wheat at the bottom of the hill.

Then he turned around again.

Little Wolf was still there under the tree.

Big Wolf smiled. Little Wolf looked even smaller.He reached the edge of the forest and turned around one last time.

Little Wolf was still there under the tree, but he was now so small that only a wolf as big as Big Wolf could possibly see that such a little wolf was there.

Big Wolf smiled one last time and entered the forest to continue his walk.

But when he reemerges from the forest by evening, the tiny blue dot is gone from under the tree.

At first, Big Wolf assures himself that he must be too far away to see Little Wolf. But as he crosses the wheat field, he still sees nothing. We watch his silhouette tense with urgency as he makes his way up the hill, propelled by a brand new hollowness of heart.

Big Wolf felt uneasy for the first time in his life.

He climbed back up the hill much more quickly than on all other evenings.There was no one under his tree. No one big, no one little.

It was like before.

Except that now Big Wolf was sad.

“The joy of meeting and the sorrow of separation,” Simone Weil wrote in contemplating the paradox of closeness, “we should welcome these gifts … with our whole soul, and experience to the full, and with the same gratitude, all the sweetness or bitterness as the case may be.” But Big Wolf feels only the bitterness of having lost what he didn’t know he needed until it invaded his life with its unmerited grace.

That evening for the firs time Big Wolf didn’t eat.

That night for the first time Big Wolf didn’t sleep.

He waited.For the first time he said to himself that a little one, indeed a very little one, had taken up space in his heart.

A lot of space.

By morning, Big Wolf climbs his tree but can’t bring himself to exercise — instead, he peers into the distance, his forlorn eyes wide with sorrow and longing.

He bargains the way the bereaved do — if Little Wolf returns, he vows, he would offer him “a larger corner of his leaf blanket, even a much larger one”; he would give him all the fruit he wanted; he would let him climb higher and mirror all of his exercises, “even the special ones known only to him.”

Big Wolf waits and waits and waits, beyond reason, beyond season.

And then, one day, a tiny blue dot appears on the horizon.

For the first time in his life Big Wolf’s heart beat with joy.

Silently, Little Wolf climbs up the hill toward the tree.

“Where were you?” asked Big Wolf.

“Down here,” said Little Wolf without pointing.

“Without you,” said Big Wolf in a very small voice, “I was lonely.”

Little Wolf took a step closer to Big Wolf.

“Me too,” he said. “I was lonely too.”

He rested his head gently on Big Wolf’s shoulder.

Big Wolf felt good.And so it was decided that from then on Little Wolf would stay.

Complement the immeasurably lovely Big Wolf & Little Wolf with Seneca on true and false friendship and astronomer Maria Mitchell on how we co-create each other in relationship, then revisit other thoughtful and touching treasures from Enchanted Lion: Cry, Heart, But Never Break, The Lion and the Bird, Bertolt, The Paper-Flower Tree, and This Is a Poem That Heals Fish

Illustrations courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books; photographs by Maria Popova