Beethoven’s advice on being an artist

Beethoven’s advice on being an artist: His touching letter to a little girl who sent him fan mail, by Maria Popova

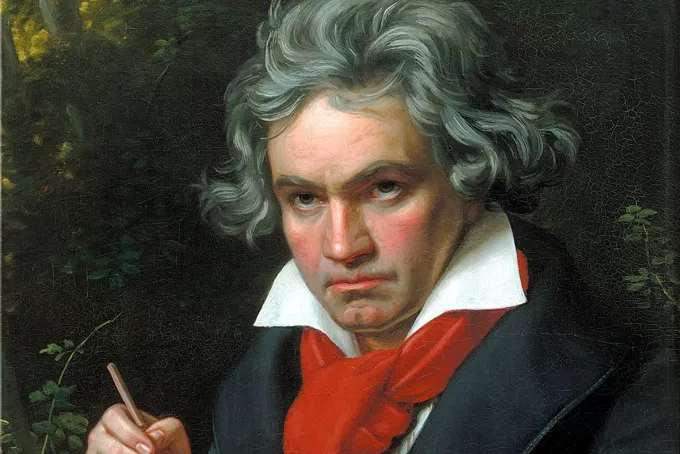

“The true artist is not proud… Though he may be admired by others, he is sad not to have reached that point to which his better genius only appears as a distant, guiding sun.”

“The Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order to know himself,” E.E. Cummings wrote in contemplating what it means to be an artist — a sentiment which intimates that the accumulation of learning, an inevitable byproduct of the process of growing up, takes us not closer to but further away from our creative source.

Baudelaire captured this perfectly when he wrote: “Genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.” This, perhaps, is why some of humanity’s most fertile minds have traced the origin of their creative purpose in childhood moments of epiphany.

Pablo Neruda in his anecdote of the hand through the fence, Patti Smith in her encounter with the the swan, and Albert Einstein in his formative memory of the compass.

In speaking with children, therefore, one might be able to get to the heart of art most simply and directly, unobstructed by the learned assumptions with which the act of living cloaks the act of creation.

In speaking with children, therefore, one might be able to get to the heart of art most simply and directly, unobstructed by the learned assumptions with which the act of living cloaks the act of creation.

In the summer of 1812, a young aspiring pianist named Emilie sent her hero a beautiful hand-embroidered pocketbook to express her admiration for his artistic genius. Touched by the gesture, 41-year-old Beethoven wrote back, offering some simple yet profound words of encouragement and advice on the creative life — an exquisite micro-manifesto for what it means to be an artist and what art demands of those who make it.

In a letter from July 17 of that year, found in Beethoven: Letters, Journals and Conversations (public library) — which also gave us the great composer’s stirring letter to his brothers about how music saved his life — Beethoven writes to Emilie:

My dear good Emilie, my dear Friend!

[…]

Do not only practice art, but get at the very heart of it; this it deserves, for only art and science raise men to the God-head. If, my dear Emilie, you at any time wish to know something, write without hesitation to me. The true artist is not proud, he unfortunately sees that art has no limits; he feels darkly how far he is from the goal; and though he may be admired by others, he is sad not to have reached that point to which his better genius only appears as a distant, guiding sun.

Although known for his explosive anger, a bout of which reportedly caused his deafness, Beethoven was indeed a man of multitudes, capable at times of tremendous tenderness and sensitivity. It is from that soft and human place that he adds, in this letter to a little girl of meager means and no social advantage, a touching note on the artist’s responsibility to humility:

I would, perhaps, rather come to you and your people, than to many rich folk who display inward poverty. If one day I should come to [your town], I will come to you, to your house; I know no other excellencies in man than those which causes him to rank among better men; where I find this, there is my home.

If you wish, dear Emilie, to write to me, only address straight here where I shall be still for the next four weeks, or to Vienna; it is all one. Look upon me as your friend, and as the friend of your family.

Complement this particular fragment of Beethoven: Letters, Journals and Conversations with Einstein’s advice to a little girl on being a scientist, Sol LeWitt’s electrifying letter of encouragement on being an artist, and Rilke’s timeless wisdom on what it takes to create, then revisit Beethoven’s passionate love letters.