Beethoven 250: The ultimate song of health after illness

By Andrea Valentino

In 1825, while recuperating from a near-death experience, Beethoven composed one of the most profound pieces of music in Western history. Andrea Valentino explores how The Holy Song of Thanksgiving came about.

Few composers write pieces that are remembered centuries after their deaths – and fewer still have their notes inspire poetry. As so often with the man and his music, Ludwig van Beethoven is different. Despite lockdowns and a pandemic, fans all over the world are celebrating the 250th anniversary of his birth with typical enthusiasm, hosting talks and digital concerts from Rotterdam to Denver. In March, performers with the Berlin State Opera took to their balconies to sing excerpts from his heroic Ninth Symphony. In May, officials eagerly reopened the Beethoven-Haus, his childhood home in the centre of Bonn.

And for Ruth Padel, a British poet and musician, Beethoven and his birthday have inspired literary creation too. All the poems in her new book, Beethoven Variations: Poems on a Life, are vividly beautiful, sparked as they are by sonatas, symphonies and songs. Yet amid the coronavirus, and the death that comes with it, one of them stands out. In the Lydian Mode is based on the third movement of one of Beethoven’s late string quartets, known as the Heiliger Dankgesang – the Holy Song of Thanksgiving.

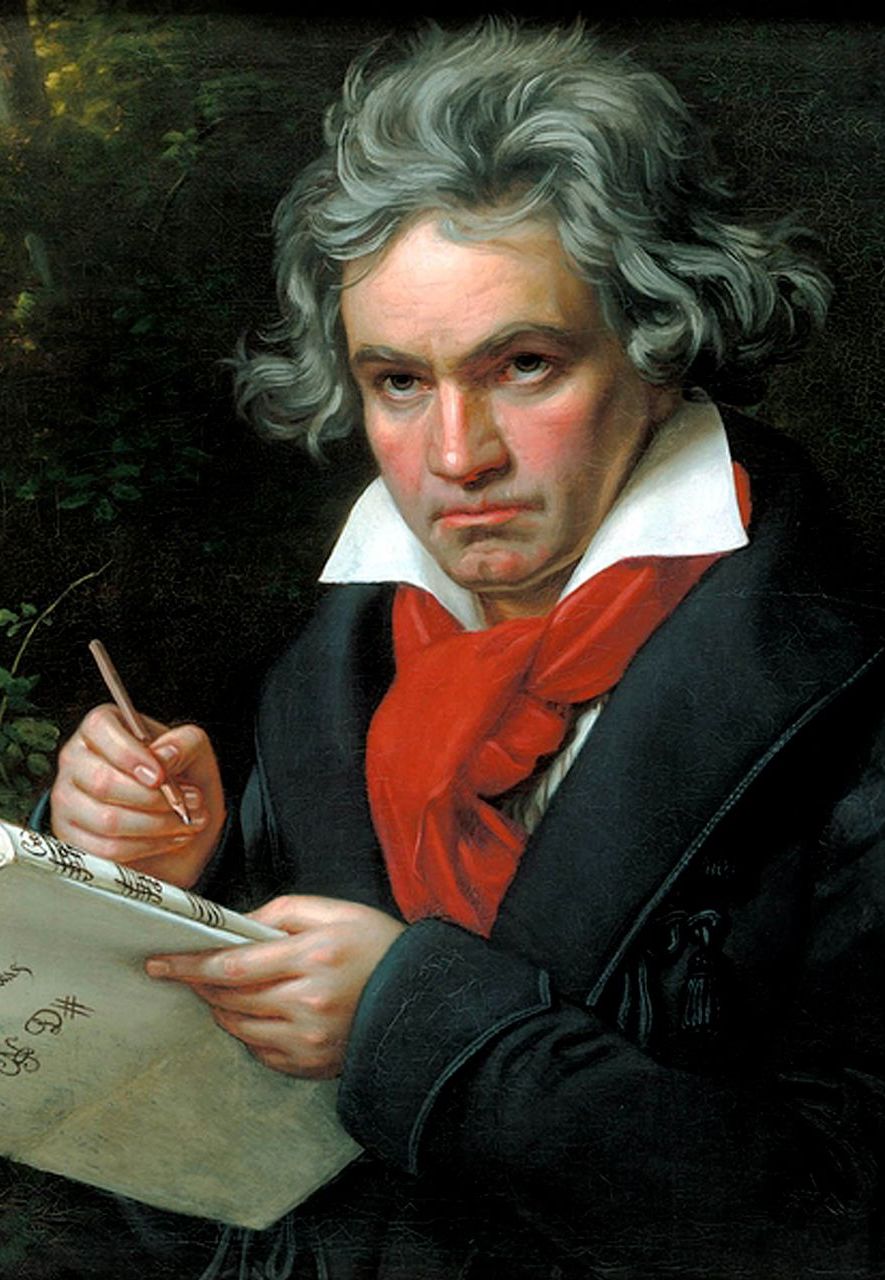

Beethoven’s Heiliger Dankgesang alternates slow sections with faster sections, representing periods of illness and health (Credit: Getty Images)

Written two years before he died, while Beethoven was recovering from a near-fatal illness, Padel sees in this sublime combination of two violins, viola and cello a tonic for our anxious and uncertain times. She says listening gives her a sense of hope and renewal – what “we have all been hoping for” over the last few months. And Padel is far from alone. For composers and musicians, this remarkable piece of music has proved irresistible, providing solace and giving strength even when the future seems lost.

Light in a dark place

The spring of 1825 was not good to Beethoven. Possibly due to his deafness, or else his angry mood swings, he felt increasingly isolated from his friends and family, complaining to his nephew about “you, and my contemptible brother, and the detestable family that I am afflicted with”. Beethoven’s own erratic behaviour may have pushed people away, too. As a servant remembered in an incident the following year, their master would “wander in the fields, calling, waving his arms about, moving slowly, then fast, then abruptly, stopping to scribble in his notebook.” Between that and his shabby appearance, 1825 even saw Beethoven detained by police – after they mistook him for a vagrant.

In the third movement of his string quartet opus 132, Beethoven offers thanks for being alive, despite having gone completely deaf (Credit: Getty Images)

Worse was to come. In April, Beethoven developed a serious intestinal illness. His doctor ordered him away from Vienna for rest at the nearby spa of Baden, and banned him from drinking wine or eating his favourite liver dumplings. As Robert Kapilow, a composer and musical commentator explains, Beethoven adored the countryside, but this trip away would be far less enjoyable. His exact condition is unclear, but from his letters he clearly feared for his life – especially when combined with his fragile mental state. “Forgive me in consideration of my very delicate health,” he wrote to the writer and critic Ludwig Rellstab at the start of May 1825. “As perhaps I may not see you again, I wish you every possible prosperity. Think of me when writing your poems.”

Start listening to the Heiliger Dankgesang and reality seems to hold its breath and wait

In the end, Beethoven did get somewhat better – and it was while recovering at Baden that he wrote the Heiliger Dankgesang. Even if a dumpling-free diet really did help his recovery, the composer himself looked to a higher power. As he notes, the movement is a Holy Song of Thanksgiving of a Convalescent to the Deity, in the Lydian Mode. “It is clearly a statement of faith,” explains Edward Dusinberre, first violinist in the Takács Quartet and an expert on the Heiliger Dankgesang. “You observe that in people who have had extremely hard lives – they have found that attitude of gratitude.”

Start listening to the Heiliger Dankgesang and reality seems to hold its breath and wait. For about three heartrending minutes, the notes come glacially – so glacially, says Michiko Theurer, a violinist who has played and studied the piece, that it almost feels like a meditation exercise. This is exactly the point. Beethoven wrote this first section of the Heiliger Dankgesang in the ‘F Lydian’ mode, a scale without sharps or flats. Combined with the molto adagio pacing, the music feels stuck in an unending desert or an infinite sea – similar, Kapilow has described, to the feeling you get trapped in hospital for days without end. This reverential atmosphere is heightened by the tune itself. The quartet pairs five short preludes with an eight-note chorale, the sort popularised by earlier religious composers like JS Bach – even if the Beethoven version is too slow to really hear.

Feeling new strength

But wait for long enough, and everything shifts. Even if you only had the score to go on, you could see it coming – Beethoven labels the second section of his piece as Neue Kraft fühlend, or Feeling New Strength. The austere music of the first few minutes suddenly collapses into an optimistic universe of harmonies and trills. Beethoven is famous for these shattering changes, of course, but Kapilow argues that the Heiliger Dankgesang is “unique” even compared to other wild Beethoven U-turns. “There are no other pieces with this staggering contrast between a Lydian mode section – the convalescent music, the sickness music, the timeless music – and the new strength section.”

TS Eliot’s Four Quartets was inspired by the opus 132; in 1933, the poet said that he wanted to get “beyond poetry, as Beethoven in his later works, strove to get beyond music”

If the movement ended there, with the triumph of health over sickness, it would be easy to understand what Beethoven was trying to convey. Having successfully beaten his illness, he was simply thanking the Almighty for his good fortune. But this music is about far more than just watching Beethoven emerge from his sickbed and trot back to Vienna. At the end of this first Feeling New Strength section, after all, the ‘convalescent music’ returns – just as ethereal as before. Listen for a few more minutes, and you get another round of Feeling New Strength. As Dusinberre says, if the Heiliger Dankgesang was just a “straightforward narrative of recovery”, why would it keep switching between fast and slow?

How, then, to explain the Heiliger Dankgesang? Perhaps the fifth and final part of the movement can help. At the end of the second New Strength section, the slow pace returns again – but only for a moment. From there the original eight-note chorale is reduced to five notes, then three, then two, then one. At the same time, the simple accompanying prelude becomes more complex, turning the whole soundscape into a floating world of transcendental emotion, the composer ordering musicians to play with the “utmost, deepest, and sincere feeling”.

As with other Beethoven works, Kapilow sees this mix of sophistication and simplicity as “the summation” of the composer and his music, suggesting that you can see the fundamentals of his “core character in a single note” or two. Padel makes a similar argument, wondering if the sublime music is an attempt to “split off” his turbulent personal life from his idealised musical one.

Eliot wrote, in 1933, that Beethoven’s later works contained a gaiety “which one imagines might come to oneself as the fruit of reconciliation and relief after immense suffering”

The composer himself appears to agree. In the middle of his illness, Beethoven sent a short piece of music to his doctor. The accompanying lyrics proclaim:

Doctor, close the door against death,

Notes will help him who is in need.

To put it another way, if the Heiliger Dankgesang is partly an uncomplicated prayer of thanks to the Almighty, and partly a meditation on sickness and health, it may also symbolise the immense power of music – notes – to keep people going in times of strife. Nor is Beethoven alone in using his music this way. Battling leukaemia shortly before his death in 1945, the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók quoted the Heiliger Dankgesang in his last piano concerto. After surviving a violent heart attack, Arnold Schoenberg may have been influenced by the movement in his 1946 string trio. For her part, Padel has read In the Lydian Mode at funerals, and suggests that her poem and the soaring music it represents may help listeners find calmness in sorrow. Theurer agrees. “I think that both playing and listening to [the movement] can be a deeply healing experience”.

Little wonder that the Heiliger Dankgesang has special resonance now – both Padel and Kapilow describe the deep impact the piece has on them during the current pandemic. With the Takács Quartet, moreover, Dusinberre recently performed the movement for an online concert, and recounts “the inner peace” the experience gave him. “In the midst of these awful circumstances – people are dealing with such uncertainty and illness and death – to play a piece like this can give us hope. That is where the power of the music is.”

And if his brush with mortality inspired Beethoven to write one of the most poignant works in all of Western music, Kapilow wonders if our own deep isolation might spark similar ingenuity – whether artistically or in the struggle for social justice. “Not only does a pandemic or a health crisis give you time to reflect, it changes who you are on the other side,” he says. “There is a tremendous awareness now of the inequality in America. If we could come out with anything as a country [like] what [Beethoven] came out with in the Heiliger Dankgesang, it might even have been worth it.” A lovely idea – and surely one that would have made even the peevish convalescent raise a smile.