Bartók and Nature

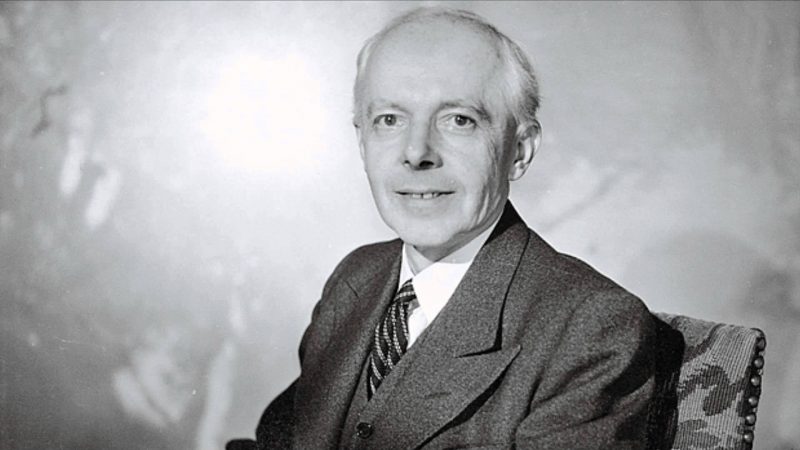

Béla Bartók’s first ballet, The Wooden Prince (1916) takes us to the story land of princes and princesses, and, of course, evil fairies. But, to get it on stage, Bartók had to contend first with the evil management of the opera house where it was to be staged. He had presented the Royal Opera House in Budapest with his first opera, Bluebeard’s Castle, in 1911. They accepted it but put it aside and looked elsewhere for operas. Finally, in 1916, when Bartók had completed The Wooden Prince and had it successfully staged at the Royal Opera House as a ballet, the Royal Opera House put on Bluebeard’s Castle in 1918.

The story line for The Wooden Prince was written by Béla Balázs, who had also written the libretto for Bluebeard’s Castle. The story appeared in the Christmas 1912 issue of the journal Nyugat (The West). The story starts with, as it always does, a prince spying a princess playing in the forest. He, of course, falls in love and she knows nothing of this. Then it all goes sideways: a fairy in the forest sees the prince and wants him for herself. She causes the trees to make the obstacles to the prince’s quest, then the forest stream rises against him. All the time, the princess sits in her castle, spinning yarn. Finally, to fool the fairy, the prince makes a wooden mannequin that he dresses in his cloak, puts his crown on it, along with a lock of his hair. The fairy brings the Wooden Prince to life and the princess, of course, falls in love with it. The real prince is left behind in despair. The fairy relents, makes the Wooden Prince lifeless again, and the princess finally beholds the real prince.

It’s mystical and magical, and like many stories, has a happy ending. Bartók’s music carries the magical side of the forward, beginning with a quite aetherial opening, which is often compared to the opening of Wagner’s Das Rheingold.

Later, when the fairy is creating obstacles for the Prince, she enchants the stream and we are in a water world.

We can hear the grotesqueries in the dance between the princess and the Wooden Prince. This is the same style of folklore music that we’ve heard in other Bartók pieces where he uses the Hungarian verbunkos dance.

Bartók: A fabol faragott kiralyfi (The Wooden Prince), BB 74: Fourth Dance: Dance of the Princess with the Wooden Prince (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

The critical part of the work for Bartók wasn’t the story itself, but the interaction between the fairy and the prince. Once the princess had fallen in love with the Wooden Prince, the prince was in despair. The fairy realizes the depth of his pain and takes him to a tall hill in the middle of the forest. She has all the trees, flowers, and waters of the forest pay him homage and shows him the world from the hill – the prince realizes here the folly of pursuing love and that only Nature can provide solitude.

At the end, the prince and princess embrace and we return to the calmness of the opening movement, and now we realize that the beginning is the ending again – the calm of the forest returns.