I hated Mahler – So this is how I tried to understand his music

Music that’s everything

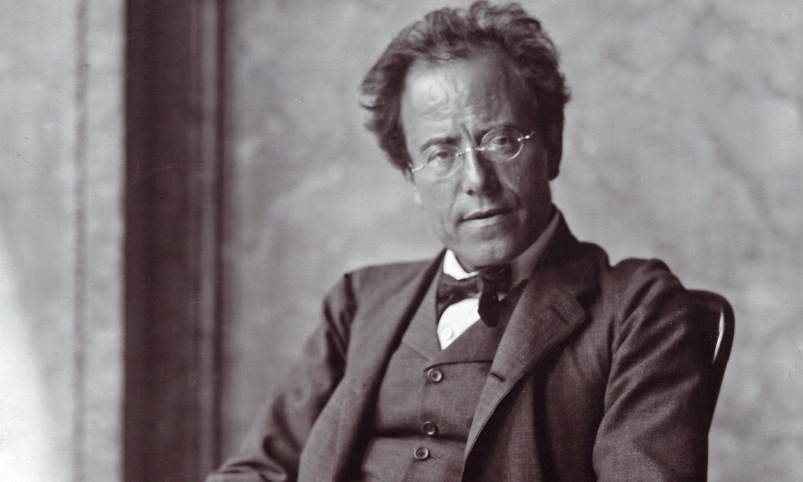

First loathing, then loving, the all-encompassing symphonies of Gustav Mahler.

I never cared much for the music of Gustav Mahler. I tried to like it, but without success. The problem, for me, wasn’t that Mahler was modern or unapproachable or “difficult.” Somehow, and despite a natural predisposition against modernism of all kinds, I had learned to appreciate the music of Schoenberg and particularly Shostakovich. Mahler’s symphonies, though, which in one sense are much more approachable and “tonal” than that of modernist composers (he’s commonly categorized as “late Romantic” rather than modern) struck me as deliberately incoherent. Twenty years ago I bought recordings of all nine, listened to them dutifully, but with only the partial exception of the First Symphony, the “Titan,” couldn’t make anything of them. I’ve seen various ones performed on different occasions, but rarely with profit. His famous remark to the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, endlessly recited in discussions of Mahler’s music—“The symphony is the world! The symphony must embrace everything!”—sounded to me like highfalutin hooey.

What was it that irritated me about it? Mahler frequently gives you a ravishingly beautiful passage, but then overtakes it with a completely different thematic idea that (a) sometimes isn’t even in the same key and (b) seems designed to convey a mood totally foreign to the first one. Or he begins with a well-wrought melody, but rather than develop it or transition from it, he combines it with some angular phrase and develops that. Or he gives you an inane little fragment of a melody and creates a mad orchestral dance around it, as if the melodic fragment had been worth something in the first place. That, at any rate, is how I felt about it.I didn’t get it. Great composers always seem to be saying something with their music, and whatever Mahler was saying didn’t make sense to me.This bothered me, though. The list of musicians who hold Mahler’s music in high esteem is a long and imposing one; it includes at least two friends whose opinions I value, as well as two of my own favorite conductors, John Barbirolli and Bruno Walter, the latter having been primarily responsible for reviving Mahler’s music in the three or four decades after the composer’s death. I felt reasonably sure that I had to be wrong about this music, but I couldn’t see how and didn’t have the time or patience to figure it out.Which brings me to August of this year. Earlier in the year, I planned to be in Edinburgh for several days during the city’s yearly music festival, and the only musical event I could make it to was—I was disappointed to find—a performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. It would be undertaken by the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by its music director, Daniel Harding.Maybe, after all, it was time for me to make some attempt at understanding why apparently intelligent people insist on the greatness of this, as it seemed to me, hopelessly muddled and perverse music. It quickly became an obsession. I spent more than three months listening to nothing but Mahler and reading little but books and articles about him and his music.Mahler was born in 1860 to Jewish parents in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). There’s very little evidence of happiness in his childhood, and it’s probably true that the anguish of his early years pervades all his work. Sigmund Freud, whom Mahler visited in 1910, recorded that the composer’s “father, apparently a brutal person, treated his wife very badly, and when Mahler was a young boy there was an especially painful scene between them. It became unbearable to the boy, who rushed away from the house. At that moment, however, a hurdy-gurdy in the street was grinding out the popular Viennese air, ‘O du lieber Augustin.’”Whether Freud was reading the subconscious effects of Mahler’s past into his music is hard to say. But almost everyone who knew Mahler seems to have remarked on the unpredictability and strangeness of his demeanor. The aforementioned Bruno Walter, for instance, remembered

the vehemence with which [Mahler] objected when I said something that was unsatisfactory to him . . . his sudden submersion into pensive silence, the kind glance with which he would receive an understanding word on my part, an unexpected, convulsive expression of secret sorrow and, added to all this, the strange irregularity of his walk: his stamping of the feet, sudden halting, rushing ahead again—everything confirmed and strengthened the impression of demoniac obsession.

That, if you’re unfamiliar with Mahler’s music, reads like a visual image of it. “He can switch from the most passionate approval to the most violent disagreement without any transition whatever,” Mahler’s friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner remembered, “and he can overwhelm you just as easily with unreasoning love as with unjust hatred.” His wife Alma recalled that after hearing a rehearsal of the Sixth Symphony in Essen, Mahler “walked up and down in the artists’ room, sobbing, wringing his hands, unable to control himself.”

None of this means Mahler’s music is any good, of course—a volatile personality refracted through a musical score doesn’t make the music worth listening to—but it does I think get at what Mahler was trying to accomplish. He once wrote about how he had intended to call his Third Symphony a “symphonic poem” until he asked himself what a symphony was. “The term ‘symphony’—to me this means creating a world with all the technical means available. The constantly new and changing content determines its own form. Mahler, if I’m interpreting these and similar remarks by him correctly, was in some way trying to transmit the whole of his mind and affections and character into his art.

I began to wonder if this latter declaration about the nature of the symphony, together with the remark to Sibelius about the symphony being “the world,” might actually mean something. Listening to his massive, sixty- or seventy-minute symphonies, bursting as they do with ideas and moods that compete with each other in sometimes startling ways, I began to suspect that for Mahler the word “world” wasn’t just a synonym for the abstract idea of all things everywhere, as I had assumed—that would have made his remark meaningless—but instead signified the actual world he inhabited and experienced. It seemed to me that Mahler was trying to make his symphonies communicate the whole diverse conglomeration of ideas and emotions that make up an individual human life. No work of art can accomplish that end, of course—art is not life—but the thought that that’s what Mahler was attempting began to make his music seem coherent. Or at least not totally incoherent. The sheer superhuman immensity of his symphonies still strikes me as too great for ordinary mortal comprehensibility, but then so do a lot of things that are no less real and rewarding for that. These thoughts were in my mind as I listened to the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Edinburgh’s Usher Hall. The Hall had been substantially renovated since I was there last, and there was a crispness to the sound I’m certain I would have noticed without any knowledge of the revamp. The SRSO played cleanly and lyrically but with violent lunacy at the right moments, even the notoriously difficult brass unerring in its execution. Indeed in Ninth’s tutti passages, and particularly in the haywire coda of the third movement, the orchestra was almost deafening—aurally and mentally devastating, no doubt as Mahler intended it to be. As I listened to this colossal work of art, engrossed by it and actually enjoying it for the first time, I tried to think of an analogy for what Mahler had done. Writers trying to find ways of explaining Mahler’s music frequently draw on images and metaphors of death, and fair enough; the Ninth Symphony’s final movement is pretty obviously a long, death-like farewell. But there is far more than death here. Perhaps Mahler was attempting to do something akin to what the writer of Genesis attempted in narrating the life of Joseph. It is a sprawling story that takes in greatness of character and inextinguishable human love, but also mischance, pettiness, hatred, stupidity, deceit, self-absorption, greed, and of course death.

The story is an intensely beautiful one, including though it does many unsavory details one might have assumed a myth-making historian would leave unrecorded. It is the story (to put it briefly) of how one vicious and cowardly act of human trafficking turns out to be, in the sublime superintendence of God’s quiet governance, the very thing that keeps a tribe of families from destruction. “You meant evil against me,” says Joseph at the story’s end, “but God meant it for good.” So much of a Mahler symphony is jarring and confusing and unhappy, but somehow he stitches its themes together in ways that always seem natural—his transitions never sound forced—and the whole, once you’re able to take it in, forms a thing of great humaneness and power. I wonder the degree to which Mahler had internalized this Judaic aesthetic, if that’s not an unduly literary way to put it.

Many of the Hebrew Bible’s histories read this way: An untidy series of mistakes and betrayals and partial gains leads in time to fulfillment and rest. We know that as a child Gustav was an “excellent” student in Judaic studies, and many scholars have pointed out the Jewish influences apparent in his works, especially the Second Symphony, “Resurrection.” The analogy of his music to the life of Joseph is probably a fanciful one, but it is not preposterous.Mahler’s achievement, if I’m right, was to translate the things that make human life by turns fulfilling and painful, elegant and stupid—the tawdriness, the chaos, the dignity and comedy and splendor—into exquisitely beautiful works of art. They are overpowering and outrageous in their scope, but beautiful all the same. Six months ago I didn’t see the point of Mahler’s music. Now, as I write, I hear the jokey pulsations and majestic horn trills of the Ninth’s second movement in my head, and it’s hard to see the point of anybody else’s. Barton Swaim is author of The Speechwriter: A Brief Education in Politics (Simon & Schuster, 2015).