‘The Planets’ At 100: A Listener’s Guide To Holst’s Solar System

by Gustav Holst

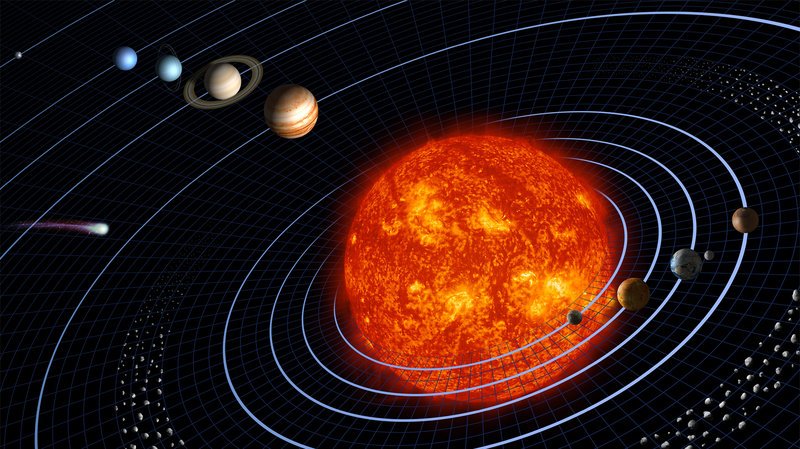

One hundred years ago, a symphonic blockbuster was born in London. The Planets, by Gustav Holst, premiered on this date in 1918. The seven-movement suite, depicting planets from our solar system, has been sampled, stolen and cherished by the likes of Frank Zappa, John Williams, Hans Zimmer and any number of prog-rock and metal bands.

To mark the anniversary, we’ve enlisted two experts to guide us on an interplanetary trek through Holst’s enduring classic.

First, someone who knows the music: Sakari Oramo, chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, opened this summer’s Proms Festival, London’s biggest classical music event, with The Planets. “The work has always exhilarated me,” Oramo says. “Each of the planets has a different style of orchestration and that’s why it stays interesting all the time for the ear.”

Next, someone who knows the real planets. Heidi Hammel is a planetary astronomer who specializes in the outer planets, and the executive vice president of AURA, the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

Holst, however, was no astronomer. He was more of an astrologer; his inspiration came from the personalities of the planets. He gave each of them nicknames (not related to their Roman counterparts) like “Mars: The Bringer of War” where we begin our planetary trek. Oramo says Holst un-holsters the big guns in his explosive first movement.

Mars

“Mars is a war machine,” Oramo says. “You could refer to Mars as the forefather of music for films describing interstellar warfare.”

Since we’re talking movies, what about the “Imperial March,” perhaps the most recognizable music John Williams wrote for Star Wars? I played a clip of it for Oramo as we discussed Holst’s music.

“Yes, Star Wars. Oh, I love it!” Oramo says. But isn’t it a rip-off of “Mars?”

“I wouldn’t call it a rip-off,” Oramo answers. “It’s based on the principals Holst created for ‘Mars.’ And all composers steal from each other.”

(And some get caught. Oscar-winner Hans Zimmer was sued by the Holst Foundation for writing music an awful lot like “Mars” in his score for Gladiator.)

Venus

Holst’s second movement brings us to “Venus: The Bringer of Peace.” The planet is named after the goddess of love.

“Venus is not a loving place at all,” our astronomer Hammel notes. “It’s a hellish landscape which is so hot lead would melt on its surface.”

Hellish maybe, but Oramo says its music couldn’t be more opposite from “Mars.”

“Venus is beautiful but enigmatic,” Oramo says. “It has achingly beautiful music for the winds and horn. I find ‘Venus’ one of the most rewarding movements to conduct because it has this kind of fragility and sensitivity about it.”

Mercury

Heading closer to the sun, we arrive at Mercury, which Holst subtitled “The Winged Messenger.”

“Mercury is a very active, bouncy figure,” Oramo notes. “It’s definitely a creature with wings.”

“Something crazy about ‘Mercury,'” Hammel adds, “is that even though it’s so close to the sun, and it’s just being baked in the sun’s heat, it does have craters. And some of those craters are deep enough that they have shadows that are cold and have ice in them.”

Jupiter

Gustav Holst’s Planets don’t exactly line up like the real ones — he skips Earth and Pluto, which wouldn’t be discovered until a dozen years after The Planets premiered. So after “Mercury” we skip on to “Jupiter: The Bringer of Jollity.”

Jupiter is the giant among our planets — so big says Hammel, it’s like a small solar system unto itself.

“It’s got a whole retinue of moons,” she says. “Seventy-nine moons now. That’s a lot of moons.” Also, she doesn’t get the whole “jolly” thing. “I don’t think of Jupiter as a jolly old soul,” she says. “When I listen to these themes, it doesn’t make me think of happy things. I think of grandness, expansiveness.”

One expansive thing about Holst’s “Jupiter,” Oramo says, is the sheer number of great tunes orbiting within the movement. One of them, a jaunty melody fueled by strings and brass, Oramo calls “rumbustious.”

“It’s like an elephant in a porcelain shop,” he says, “very happily destroying everything and being very glad about it.” The tune was so catchy it was hijacked by the British rock group Manfred Mann’s Earth Band, in 1987.

Saturn

And now we approach the outer planets, with “Saturn: The Bringer of Old Age,” where time ticks away like an old clock. Flutes rock back and forth while Holst gives a glacially paced theme to the double basses.

“Saturn’s main claim of course is its fantastic ring system,” Hammel says. But what are those rings made of? “Sometimes people say they’re the lost airline luggage,” Hammel says with a chuckle. (That’s an astronomer’s joke.) Actually, she explains, the rings are particles of dust and ice, some as big as a house.

Uranus

Leaving Saturn now, our next stop is Uranus, the planet which gets pronounced in two ways. Hammel says astronomers pronounce it YER-ah-nuss. (Eighth grade boys may stress a different syllable.) Holst subtitled his “The Magician.”

“Making magic not necessarily for the purpose of common good,” Oramo explains. “It’s slightly vulgar. It has this slight nastiness in the rhythm.” Beginning with a fanfare of brass and timpani, “Uranus” struts around and eventually falls into a clumsy march tune that runs amok, ending with a huge glissando on the pipe organ.

Neptune… and beyond

Finally, there’s “Neptune: The Mystic.” Holst does not end his cycle as he began it, with a big bang. Instead the music is quiet and slow-paced.

“Being an astronomer who has studied this planet, this movement is one that is actually aligned with my mental interpretation of the planet,” Hammel says. Neptune is so far from the sun she says, that the sun just looks like a moderately bright star. “When I listen to the movement I hear mysticism through and through,” she says. “It’s quiet, it’s very questioning, it’s sensitive.”

“It’s soft music for large orchestra,” Oramo says. “It has some strange halo effect and it shimmers rather than shines. Holst uses effects like harp glissandos and celeste figures that float inside the chords of the rest of the orchestra.”

But Holst’s true masterstroke is how he incorporates an offstage wordless female choir halfway through the movement.

“They are there, but they’re not there,” Hammel says. Like the most distant worlds in our solar system, she says, “they are shrouded in secrecy.” Oramo says it’s ethereal, “radiating a strange, foreign light that is not light known to us.”

Astrologers equate Neptune with transcendence, myth and hope. Holst’s musical version never really ends. As the choir slowly drifts away, far into the cosmos, it seems to ask: What else is out there?

“We have the capability now to build the tools that can look at planets around other stars and tell us if there are signs of life there,” Hammel notes. “We just have to choose to do it. Whether we will or not is something that’s above my pay grade.”