The bittersweet inside story behind Brahms’s op.9 Variations

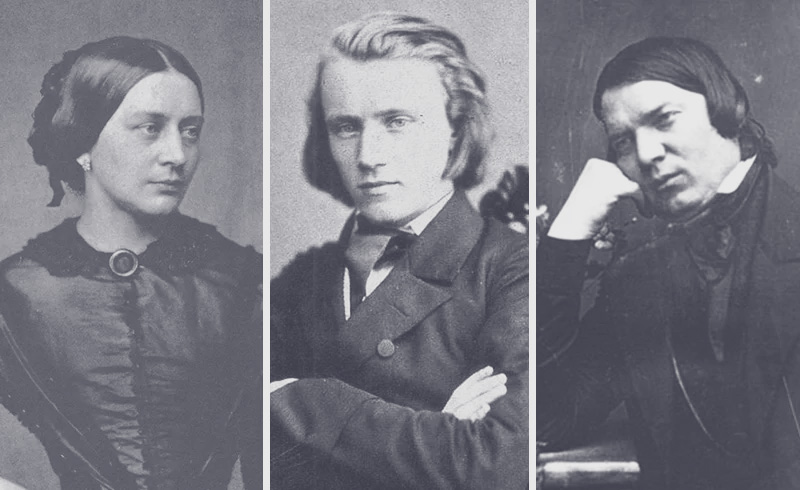

At the Center of the Musical Universe Robert and Clara Schumann

Brahms first visited the couple in Düsseldorf on 30 September 1853, and he stayed for four weeks. Both welcomed him warmly, and Robert was highly enthusiastic about the young man’s compositions; he even called him a genius and the coming savior of German music! Clearly the personal and musical consequences of that meeting would have far reaching implications.

Brahms eventually left for Leipzig, but learning of Robert’s attempted suicide rushed back to Düsseldorf. He visited Robert in the hospital, often accompanied by his friends Joseph Joachim and Albert Dietrich. But he also lived with Clara and the children in the Schumann house. However you look at it, Brahms was helplessly in love with Clara. He wrote in frustration during 1855, “I can do nothing but think of you… What have you done to me? Can’t you remove the spell you have cast over me?” The situation was, to put it mildly, rather messy. Yet, moral dilemmas, feelings of anxiety and guilt, and bent up sexual frustration found expression in some of the most intimate and emotional music of the 19th century.

In 1852 Robert Schumann assembled and published a collection of small pieces written during the tumultuous years of his courtship with Clara. He called the collection Bunte Blätter (Colored Leaves), and this emotional kaleidoscope bristles with the musical ambiguity conjured from his gradually splintering mind.

Robert Schumann: Bunte Blätter, Op. 99

Clara had always been Robert’s muse. She is found in all manners of musical quotations, dedications, allusion, and outbursts of lyricism or effusiveness. The first “Albumblatt” in the set of Bunte Blätter originally featured the dedication, “A wish for my beloved fiancée on Christmas Eve 1838.” He sent it from Vienna to Clara, who was then in Paris. Robert writes, “Greetings, my darling girl. You have created an atmosphere of spring; I can see golden blossoms peeping forth all around me. In other words, your letters started me on composing, and I feel as if I should never stop. Here is my little Christmas gift. You will grasp its significance.” That significance clearly emerges in the longing motif that expresses his love for her in musical code. It is known as the “Clara Motif,” as the notes “C#-(B)-A-(G#)-A” spell out the musical pitches in her name.

In 1853, Clara set to work and composed her own set of variations on this particular theme by Robert. The mournful theme is followed by seven variations, with the last variation heavily laden with musical and extra-musical meaning. It has been suggested that this final variation “seems to go beyond any earthly limit,” a musical prayer possibly foreshadowing Schumann’s internment in Endenich within the same year. The work was finally published in the autumn of 1854, and bears the dedication “To my beloved husband, for 8 June, this poor new attempt from his old Clara.”

Clara Schumann: Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. 20

While Schumann was listening to “heavenly oratorios” in the Endenich hospital, Brahms hastened to Clara’s side. He was allocated a bedroom on a separate floor, and Clara writes “Brahms is my dearest and truest support; he has not left me since the start of Robert’s illness, but has accompanied me in all my trials, has shared in all my sufferings.” To distract himself from earthly matters, Brahms spent his time in Robert’s library, classifying and cataloguing scores and books. He wrote to a friend, “I have seldom felt as happy as I do now rummaging around this library.” Concordantly, he prepared a musical gift for Clara by secretly composing a set of variations to celebrate the birth of her seventh child. And it’s hardly surprising that Brahms selected Schumann’s Albumblatt from Bunte Blätter as his starting point.

Clara excitedly wrote to Robert, “Brahms has had a splendid idea, a surprise for you, my Robert. He has interwoven my old theme with yours. I can already see you smile.” In a rare moment of lucidity, Robert wrote to Brahms from his hospital bed. “How I long to come to see you, dear friend, and hear your lovely variations played either by you or by Clara, of whose beautiful rendering Joachim told me in his letter. There is an exquisite coherence about the whole work, a wealth of fantastic glamour peculiarly your own, and, moreover, evidence of what to me is a new development on your part – I mean the profound skill with which you introduce the theme at odd moments, mysteriously, passionately, and again let it disappear completely. Then the wonderful close to the fourteenth variation, with its ingenious imitation in the second above; the fifteenth in G flat, with its glorious second part; and the last! Thank you, too, my dear Johannes, for all your kindness to my Clara. She speaks of it constantly in her letters… Be sure and write soon to your admiring and loving friend, R. Schumann.” The graceful dedication of the Brahms Op. 9 Variations read, “To Frau Clara Schumann, on a theme by him and dedicated to her.”

Johannes Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Schumann, Op. 9