Schopenhauer on the Power of Music

“The effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence.”

“Music is at once the most wonderful, the most alive of all the arts,” Susan Sontag wrote, “and the most sensual.” A century earlier, Friedrich Nietzsche put it even more bluntly: “Without music life would be a mistake.” The question of why music holds such unparalleled power over the human spirit is an abiding one and, like all abiding existential inquiries, it holds particular appeal to philosophers.

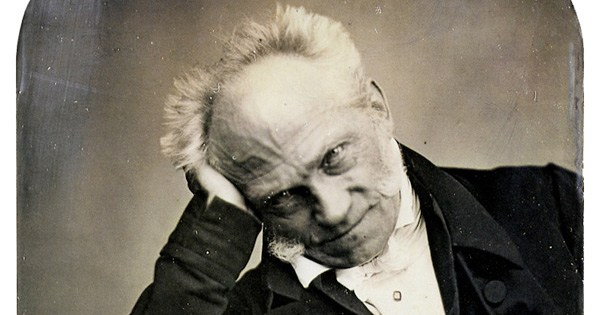

Another century earlier, Arthur Schopenhauer(February 22, 1788–September 21, 1860), a compatriot of Nietzsche’s and a major influence on him, contemplated this very question in the first volume of his masterwork The World as Will and Representation (public library) — one of Oliver Sacks’s favorite books, cited in his magnificent Musicophilia.

Schopenhauer writes:

Music … stands quite apart from all the [other arts]. In it we do not recognize the copy, the repetition, of any Idea of the inner nature of the world. Yet it is such a great and exceedingly fine art, its effect on man’s innermost nature is so powerful, and it is so completely and profoundly understood by him in his innermost being as an entirely universal language, whose distinctness surpasses even that of the world of perception itself, that in it we certainly have to look for more than that exercitium arithmeticae occultum nescientis se numerare animi [“an unconscious exercise in arithmetic in which the mind does not know it is counting”] which Leibniz took it to be… We must attribute to music a far more serious and profound significance that refers to the innermost being of the world and of our own self.

At this intersection of world and self is the will and, Schopenhauer argues, music’s unique power lies in its ability to capture precisely that:

Music is as immediate an objectification and copy of the whole willas the world itself is, indeed as the Ideas are, the multiplied phenomenon of which constitutes the world of individual things. Therefore music is by no means like the other arts, namely a copyof the Ideas, but a copy of the will itself, the objectivity of which are the Ideas. For this reason the effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence.

[…]

The inexpressible depth of all music, by virtue of which it floats past us as a paradise quite familiar and yet eternally remote, and is so easy to understand and yet so inexplicable, is due to the fact that it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality and remote from its pain. In the same way, the seriousness essential to it and wholly excluding the ludicrous from its direct and peculiar province is to be explained from the fact that its object is not the representation, in regard to which deception and ridiculousness alone are possible, but that this object is directly the will; and this is essentially the most serious of all things, as being that on which all depends.

Long before contemporary psychologists came to study the psychology of repetition and how it enchants the brain, Schopenhauer adds:

How full of meaning and significance the language of music is we see from the repetition signs, as well as from the Da capo which would be intolerable in the case of works composed in the language of words. In music, however, they are very appropriate and beneficial; for to comprehend it fully, we must hear it twice.

Schopenhauer summarizes the singular power of music:

Music expresses in an exceedingly universal language, in a homogeneous material, that is, in mere tones, and with the greatest distinctness and truth, the inner being, the in-itself, of the world, which we think of under the concept of will, according to its most distinct manifestation.

Complement this particular portion of the wholly invigorating The World as Will and Representation with other great thinkers on the power of music, Wendy Lesser on how music helps us grieve, and Aldous Huxley on why music sings to our souls, then revisit Schopenhauer on style and the significance of boredom.