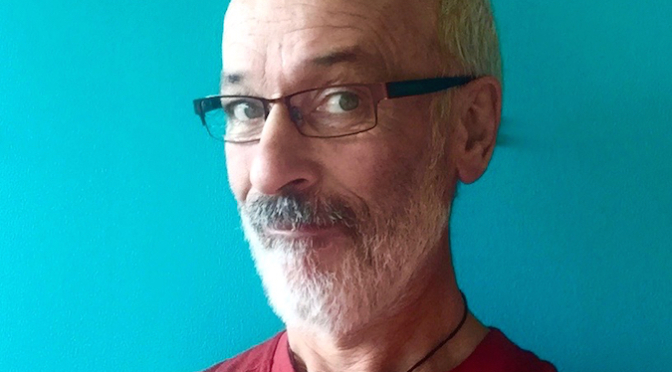

Music therapy is helping me recover from Aphasia

Stephen Gibbs had a stroke two years ago, and developed aphasia as a result. The neurological condition affects a person’s ability to communicate, and left the Wellingtonian essentially mute. A musician and music teacher – amongst other things – by trade, Stephen turned to music therapy and writing as part of his recovery. Doing so has made a big impact on his capacity to communicate and create, and he is now also the Wellington Community Aphasia Advisor for Aphasia NZ.

Sarah spoke to Stephen about the role music has played in his recovery ahead of Music Therapy NZ’s Finding Your Voice Symposium on August 12-13.

What is music therapy?

It is a way of engaging musical elements to bring positive therapeutic results.

Can you describe how it works?

The elements of music are various. Obviously the basic elements are rhythm and timbre – the tone quality of the instrument or voice. Rhythm is subdivided into pulse, beat or other rhythms. Then there is melody, harmony, dynamics, form, style. The repetitive nature of rhythm and melody and their form are very helpful for people struggling to make communicative sense. It is about fluency. The other thing is, music crosses the boundaries of the brain’s hemispheres – left and right. It is mathematical and affective. It is structured and emotional. It is language and poetry.

Why do you think making music is such a powerful form of therapy?

As I said, music crosses the boundaries of the brain’s hemispheres, and it remains in the memory much longer than ‘facts’. It is an important part of our emotional and spiritual being. When words fail, music is there.

What are some of the issues music therapy can help people with?

Speech, obviously! Memory, such as with dementia, coordination – physical, mental, spiritual – sociability, success-factors. And fun!

How has it aided your own recovery from aphasia?

Most of my musical skills were intact – thankfully. I had no paralysis, my brain was fine, and my limbs were quite functional. But I had dyspraxia too – I couldn’t form the words that I intended to use. Some of my music therapist Andrea Robinson’s exercises improved my formation of syllables in a musical way. Pitch and rhythm. “Koo, kaa, key / koo, kaa, key / koo, kaa, key” up the scale!

“The repetitive nature of rhythm and melody and their form are very helpful for people struggling to make communicative sense.”

About 2-3 months on, I couldn’t speak my address – it was mumbo-jumbo, literally! But Andrea set my address to music, and lo and behold – I could sing it. It was much easier to sing than speak. My fluency was much better. It is the opposite of learning to sing! Usually, for singing, we speak, then engage rhythm and then the melody. My talking has improved, but my singing is still better.

Can you describe your journey so far?

That is an interesting question! For a while, 6-12 months after my stroke, I didn’t realise that my aphasia was a ‘problem’. I knew that people couldn’t understand me, but I was quite blasé – like a stunned mullet! Every so often, I was pulled up short when people thought I was mentally defective! The people – the person – more affected was my family and colleagues, and my wife. They were so supportive of me, but particularly my wife who had to care and cosset and cajole me.

One of my favourite quotes is from Nelson Mandela: “There is nothing like returning to a place that remains unchanged to find the ways in which you yourself have altered.” I have been ‘altered’, but now I have a new perspective and a new direction.

Writing was also an important part of your recovery following your stroke, why do you think that is?

I always wrote things down. Obviously, for my job – teacher, journalist, marketing director, event coordinator – but also personally. I have always logged our tramping trips, or overseas holidays. Poetry. I have a collection of quotes from a host of books that I have read. When I had my stroke, I couldn’t read or write. Two weeks after – maybe two sentences in a newspaper article and that was it. Two months after, I decide to recover my reading and writing skills. I had a blog at stephengibbsdms.wordpress.com.

“I couldn’t form the words that I intended to use.”

I started with a list of quotes. I knew that the quotes were ‘good writing’ so I copied every letter and phrase. I knew that the sentence would make sense, but I couldn’t speak it or repeat it. After a month, I was inserting one sentence by myself, commenting on the quote or my impressions of it. By one year, I was writing my own work. Every day, for 393 days, I wrote my blog. I recovered my reading and writing – mostly. What used to be a 1-hour job is now 5 hours long and I have to edit it carefully. Lots of words can be mixed up – like it, if, is. Or he and she. Now I have a review blog for concerts and events in Wellington, and I write speeches and interviews as advocacy for aphasia, and music therapy.

What were you doing before you developed aphasia?

I was a teacher for 18 years – maths and music – and I was a musician. Cello, piano, singing and composing. And I was a journalist, a writer, a marketing executive, an educationalist, a publisher, a music director and conductor, a photographer, and a event coordinator for the Te Kōkī New Zealand School of Music, Victoria University. And an apple picker, relief postie, lemon picker, tile layer. All [my professional roles] were based on speaking, discussing, writing, negotiating – lots of phone calls, emails. At the moment, I can’t do these things. Yet.

Who are the SoundsWell Singers, and what is your involvement with them?

The SoundsWell Singers are a neurological choir. Our members are people with brain injuries, aphasia, stroke, Parkinisons, dementia, and their spouse or supporters, or carers. We meet every Friday from 10:30-12. The conductors – Penny Warren and Megan Berentson-Glass – are registered music therapists. I have been a member for a year, performing with them and I have my Community Aphasia Advisor hat on too. Because I have so much experience with choirs and music in general, I can help coordinate things as well.

What does your role with Aphasia NZ involve?

I support the people with aphasia in the Wellington region and their families, providing resources and advice. I speak and advocate for aphasia awareness for groups and network with speech professionals. I attend meetings and organise meetings for people with aphasia; we have an Aphasia Hub with guest speakers on the first Wednesday of the month, a Conversation Club on the third Wednesday and a field trip on the fourth Wednesday to places of interest, like Parliament, Government House, the Police Museum, the Supreme Court, the NZ Portrait Gallery, Katherine Mansfield Cottage, the Gamelan Orchestra at NZSM.

New Zealand doesn’t have a particularly strong folk culture, in terms of people – of all ages – making music together as a community activity, whether they’re good or bad at it. What do you think music-making ‘just because’ gives to people, and how do you think a lack of opportunity to make music in that way might affect the mental and physical wellbeing of New Zealanders?

It is a interesting thought! I think it is improving – non-Pakeha cultures, Polynesian especially [have a big focus on music] – but I despair about our education system. Music teachers are not nurtured, especially at primary schools. I was a music teacher at the Steiner school, and I have particular ideas about the importance of songs and rhythm games from birth. Mum and dad singing lullabies – singing, not recordings – live music, not electronic, before puberty. That would go a long way to having a healthier society!

Stephen Gibbs is a writer, musician and the Wellington Community Aphasia Advisor for Aphasia New Zealand. Check out his blog.