How Was Musical Notation Invented? A Brief History

Imagine a piece of music. No, not the music, but the written score or sheet. Some of us look at it, and immediately begin translating those symbols into sounds. Others among us might not be able to make sense of what we see on the page — and that’s OK, because you don’t need to be able to read music to appreciate it. Musical notation is complex, and that’s a good thing because it allows composers to express complex ideas that can make their way to your ears.

But the notes and staves we see today didn’t spring fully formed from one person’s mind. Instead, the notation we see today is the product of centuries of innovation and refinement. So let’s explore a few milestones of its development.

Using notation is about as old as music itself, but for our purposes we’re going to start in the year of 1025. If you were a peasant subsisting on unseasoned cabbage, it was probably a terrible year. If you were one of the wealthy, castled minorities it was probably a good year. But if you were a monk, teaching your choir some new chants, 1025 would prove to be a downright stellar year. That was around the time a monk named Guido moved to a Tuscan city called Arezzo. Thus history has named him Guido of Arezzo.

We don’t have a ton of information concerning Guido of Arrezo’s biographical details, but that really doesn’t matter when you think about what he did. Guido contributed greatly to Western Europe’s ability to express itself musically. He organized pitches into groups called hexachords (think of them like a scale) and pretty much invented solfege (“do-re-mi-fa…”). And he advanced a method for notating those concepts more accurately. It was huge.

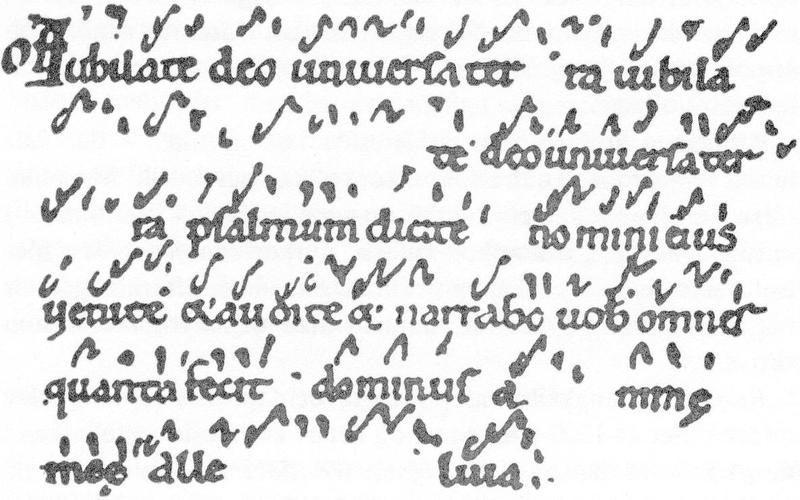

Before Guido’s time, liturgical music was (and still is) notated using markers called neumes. If you were learning a chant, you’d get some parchment with the words, and above them you’d see neumes that would slide up, or down, or twist or turn. That was your sheet music. Neumes wouldn’t tell you which note to sing, exactly; rather, they would simply indicate the contour of the melody. If a line above a word rises? Raise the pitch. Yeah, it was hard back then.

In his visits to monasteries, Guido observed just how badly the younger singers were struggling to learn chants in the repertoire. So, he thought of a nifty tool that would allow someone to sing along, even if they had never heard the music before: the staff. It had four lines, instead of the five we use today. One of them was marked with a “key indicator” — maybe a C or F — indicating its fixed pitch position. Two of those lines would be colored — yellow for C, and red for F. And so, as Guido wrote, young students could “better detect the level of pitch.” Or, you know, read the music.

A staff is great, and fixed pitches are even better. But our music is still missing something. How would you know how long to hold those notes? That was a problem for mensural notation to solve.

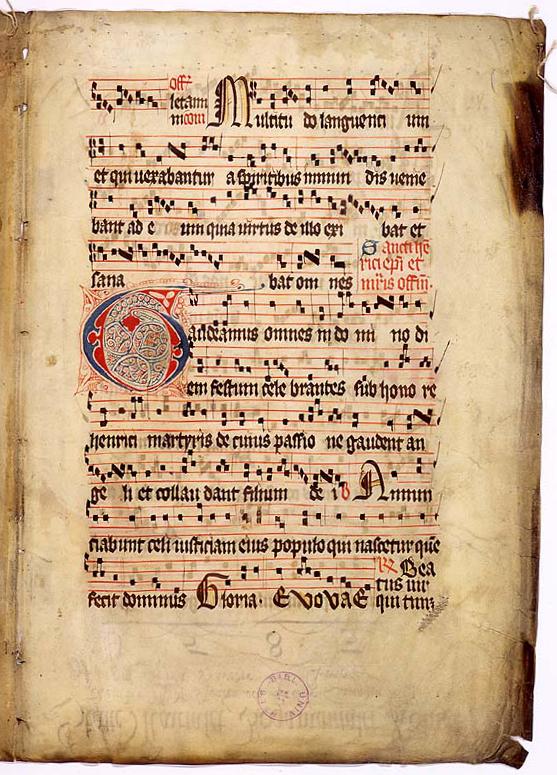

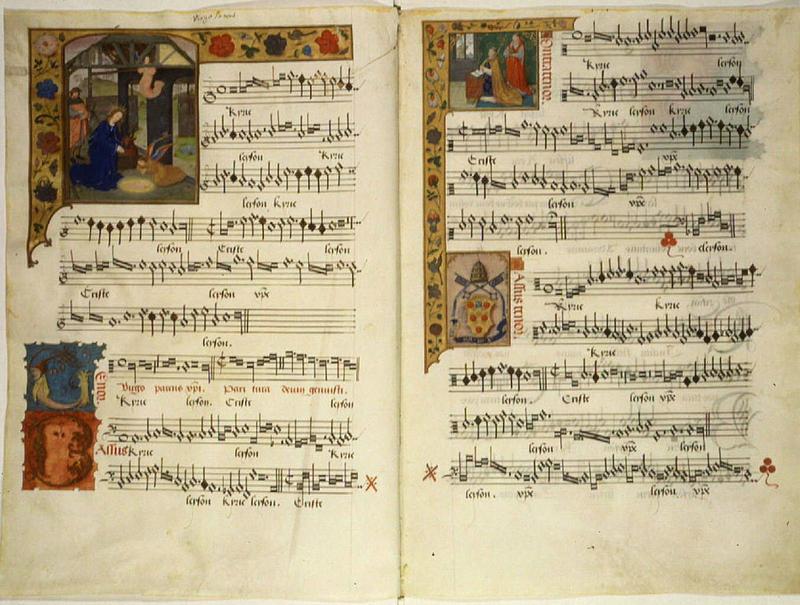

Mensural means “related to measuring things,” and that’s just what the notation of the same name set out to do. It was normally used for secular vocal music, on a five line staff. Church music was still rocking with staffed neumes, and lutists and other string players were using tablature — but mensural notation used symbols that you can very clearly see are related to modern ones.

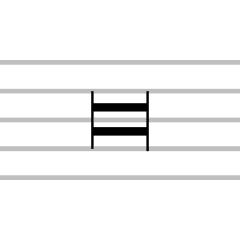

Let’s look at two note vales, longas and breves. Here they are:

Believe it or not, we still have those note values today, even though the former is rarely seen. The breve has stuck around — it’s the British English name for what Americans call double whole notes.

Each breve could be further broken down into semibreves, which could be further divided into proportionately smaller values. Corresponding rests also indicated periods of silence. Take a look at the table below for what these symbols looked like, as well as their modern counterparts.

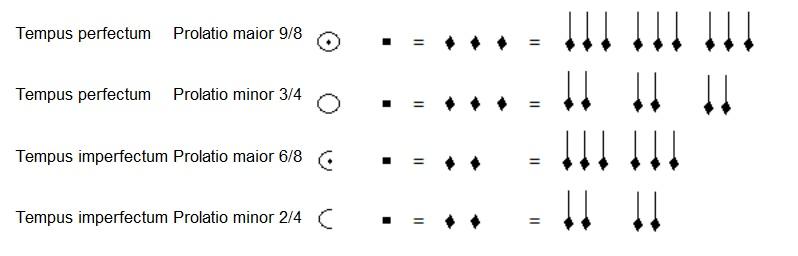

And mensural signs, which consisted of some combination of circles, half circles and dots, indicated the relationship of those notes for a piece — sort of like a rudimentary time signature. For example, it would tell the singer if it was two or three breves that made up a longa. Check out the chart below to see the possible combinations. Tempus refers to the division of breves into semibreves, and prolatio determined the relationship of the semibreve to the next smallest note value, the minim. A perfect tempus meant three semibreves made up a single breve; an imperfect tempus meant the breve consisted of just two semis. Likewise, a major prolation meant a semibreve could be subdivided into three minims; a minor prolation meant it could be broken down into two. Now take a breath, that’s all the math you have to worry about for today.

As noted before, mensural notation was largely used for secular vocal music. But around the 17th century, instrumental music came to dominate the scene. Musicians of all stripes willingly co-opted the staff and notation of the day, but found it quite limiting when it came to conveying information about what instruments other than the voice should do. So it was refined ever further. Over time barlines, stylized clefs, dynamic markings, ties and slurs began to appear.

The story behind musical notation runs pretty deep. All those bars and dots and squigglies might seem simple, but together they can form a complex language to convey some amazing creative ideas. So next time you’re getting twisted with Bach’s counterpoint or slurping up some syrupy ’70s P-Funk, think about the music. Not the sounds you hear, but instead what’s on the sheet that musicians read. Without notation, composers wouldn’t be able to convey the complex ideas required to bring your favorite tunes to life. Even if you can’t read music, you can still thank notation every day for making this possible:

*By the way, we have to note that even though he did wonders for music education, it’s risky business to credit one person with the invention of this system. Guido’s staff was probably an improvement upon the work of several others who came before him. Lines for neumes weren’t new (although Guido did extend the number of lines to four), and other coloring systems may have been present. He’s just one figure we can point to. Thems the history breaks.