10 more female composers you should know

Throughout musical history, women who wanted to write music have done so against the until recently mainstream view that women are incapable of creating high art. Today, we are beginning to appreciate the huge body of work by these women which is still, in many cases, unexplored. Here, in the second article of our series, we reveal the complex lives of ten more great female composers who deserve to be better known today.

Maddalena Casulana (c1544-90)

The first woman ever to have her own volumes of madrigals printed, Casulana was under no illusions about the prejudices facing her as a female composer – in her dedication to her patron Isabella de’ Medici Orsini at the beginning of her First Book of Madrigals (1568), she writes of her aim ‘to show to the world the foolish error of men who so greatly believe themselves to be the masters of high intellectual gifts that they cannot, it seems to them, be equally common among women’. Not a great deal is known about Casulana’s life, other than that she was probably based in Vicenza in northern Italy for much of her life. She published 66 madrigals in all, many of which display her penchant for chromaticism, dissonance and careful attention to the text. A particularly fine example is the mournful ‘Morir non puo il mio cuore’.

Marianna Martines (1744-1812)

Although her music fell out of favour soon after her death, in her day Marianna Martines was a pivotal figure in the Viennese music scene. Martines’s father was a Spanish native of Naples who had come to Vienna as a Papal diplomat. An old friend, Metastasio, who had become Poet Laureate, lived with the Martines family, acting as a sort of godfather figure to the Martines children – for the young Marianna, who showed early promise as a musician, he arranged singing and composition lessons, and keyboard tuition from a young neighbour, one Joseph Haydn. Martines’s music is typical of early-Classical Vienna (the musicologist Charles Burney described it as ‘neither common nor unnaturally new’). It is frequently virtuosic, with florid ornamentation. The composer gave many of the premieres, particularly of her vocal works, herself and the style of the writing suggests that she was an exceptionally accomplished performer. She was certainly respected as a musician, and was asked in 1773 to join the exclusive Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna. The weekly musical soiree Martines held at her home became the premier social event for musical Vienna. Among her regular guests was Mozart, who even composed some four-hand sonatas especially to perform with his hostess.

Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831)

During her relatively brief life, Szymanowska was feted primarily as a pianist. After making her debut in Warsaw in 1810, she went on to tour widely around Europe, enjoying huge acclaim and hobnobbing with the likes of composers Hummel, Rossini and Cherubini and the writer Goethe. In 1828, she finally settled in St Petersburg, where she continued to perform regularly and also ran a musical salon. Her compositions, of which there are around 100, were largely for piano (unsurprisingly) or voice. One of her major contributions was to introduce to her native Poland both nocturnes and piano studies – forms that were then famously developed further by Chopin, clearly influenced by his female forebear. Try, in particular, Szymanowska’s 20 exercises et preludes from 1819.

Adele aus der Ohe (1861-1937)

A German concert pianist and composer, Adele aus de Ohe was born in Hanover and was one of the few child prodigies accepted as a pupil by Liszt. She studied with him from the age of 12, staying with him for seven years. She made a name for herself in Europe and also in the US, with frequent concert tours. At the opening of Carnegie Hall in 1891, she performed Tchaikovsy’s First Piano Concerto with the composer conducting. ‘There was a great enthusiasm, which it was never able to produce in Russia itself,’ wrote Tchaikovsky. As a composer, Adele aus de Ohe wrote numerous songs, including settings of US poet Richard Watson Gilder, as well as piano works and compositions for violin and piano. In 1901, a concert of her own pieces at London’s Steinway Hall, featuring her Suite in E, Op. 8, was praised by The Times.

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944)

During her lifetime, Chaminade published over 400 compositions and had an international following that included Queen Victoria. Born in Paris to musical parents, Chaminade studied with teachers at the Paris Conservatoire before embarking on a career as a virtuoso pianist. After 1890, she turned to composition almost full time, and the popularity of her character works led to Chaminade clubs being set up in the US specifically to champion her work. When she finally visited the US in 1908, Chaminade was subjected to a huge amount of criticism from the press, much to do with the idea of what sort of music a woman should or should not compose. When she composed lighter, sweeter music she was criticised for writing ‘overly-feminine’ music, but when she performed her larger-scale, more developmental music she was lambasted for attempted to write music in the style of a man. Her Flute Concertino remains a staple of the repertory today, and her other large works have been compared to the works of Wagner and Liszt.

Amy Beach (1867-1944)

By the time Amy Beach was one year old, she could sing over 40 songs. When she was five, she composed works for piano in her head (without an instrument), and aged seven she gave her first public recital of music by Chopin. This prodigious musical intelligence continued throughout Beach’s teenage years, though it was tempered first by her parents and then by her husband. After her marriage to Dr Henry Beach in 1885, she was encouraged by her husband to limit her performing career to just one charity concert a year. She turned to composition but, as Henry didn’t approve of her studying with a teacher, she had to teach herself. Her Mass in E flat major was the first by a woman to ever be performed by the Handel and Haydn Society, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra premiered her Gaelic Symphony and Piano Concerto, with Beach herself as the soloist. Beach also wrote many chamber works and songs, two of which (Ecstasy and The Year at the Spring) sold thousands of copies and gave her an income for the rest of her life. After her husband’s death in 1910, she went on a concert tour of Europe, though she was forced to return by the outbreak of World War One. After that, she spent winters touring the US, and summers composing at her estate in New Hampshire until she retired to New York City in 1940.

Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979)

Rebecca Clarke was born in Harrow to a German mother and American father. Her early life was dictated by her controlling and often-abusive father who, she revealed in her late memoirs, would regularly beat his children for minor offences such as nail-biting. He withdrew Clarke from the Royal Academy of Music after her harmony teacher proposed to her, and later banished her from the family home, forcing Clarke to leave the Royal College of Music, where she had been CV Stanford’s first female pupil. She supported herself as a professional viola player, and in 1912 she became one of the six first female musicians to play in a professional orchestra when Henry Wood admitted her to his Queen’s Hall Orchestra. Clarke’s greatest composing success came during her years in the US when her Viola Sonata, was written for the 1919 Berkshire Festival of Music Competition in America, tied with a sonata by Ernst Bloch. Patron of the festival Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge eventually named Bloch the winner, but gave Clarke her first ever commission. When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Clarke became stranded in the US, where she was forced to live with her brothers. Desperate for independence, she took a role as a governess in 1942, a move that marked the end of her composing career.

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

A prodigy who died at just 24, Lili Boulanger made history when, at 19, she became the first woman to win the Paris Conservatoire’s Prix de Rome with her cantata Faust et Hélène. In doing so she trumped her composer sister Nadia (who had entered four times, winning second prize in 1908), earned herself the prizewinner’s trip to the Villa Medici in the Italian capital and won a contract with the publishers Ricordi. Ill health plagued Boulanger’s short life – bronchial pneumonia as a toddler probably led to Crohn’s Disease – but she was ambitious, phenomenally gifted and determined to make her mark. Her music displays a voice of smart originality, an ear for piquant colour and atmosphere, and a flair for text setting. All these facets are particularly shown off in the haunting Vielle prière bouddhique and bold Psalm XXIV, or in the beautiful song-cycle Clarières dans le ciel. A five-act opera La princesse Maleine, setting Maurice Maeterlinck’s play with his enthusiastic blessing, was left incomplete at her death in 1918.

Florence Price (1887-1953)

As an African-American female, Florence Price had to overcome prejudice on two fronts to become a composer. And despite growing recognition for her music, most of her 300 or so compositions are yet to be published. Born in Arkansas, Price studied with her mother and then at the New England Conservatory and, privately, with George Whitefield Chadwick. She came to national fame in 1923, when her Symphony in E minor won the Wanamaker Competition; its premiere a decade later by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra made Price the first African-American woman to have an orchestral work performed by a major American orchestra – an ensemble at the time peopled entirely by white men. Price wrote several other large-scale orchestral works, blending spirituals, African-American dance rhythms, jazz and classical idioms, and was also a prolific song composer. It was her arrangement of My Soul’s Been Anchored in de Lord that Marian Anderson sang at the end of her historic performance at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939.

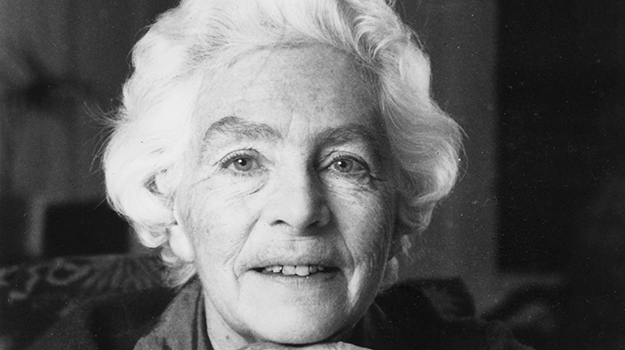

Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-94)

A blue plaque in the Essex village of Shottesbrook proudly lists Dame Elizabeth Maconchy as a former resident. She moved there in her 1950s, having already established herself as a prolific composer. Born in Hertfordshire, she spent her childhood in Ireland before returning to London to study under Vaughan Williams at the Royal College of Music. Her composing debut came in 1930 when the Prague Philharmonic performed her Piano Concerto. Maconchy’s chamber works range from a cycle of 13 string quartets to works for double bass and piano and for oboe and harpsichord. Her operas include The Sofa (1957), a mischievous story about a prince who is turned into a piece of furniture, and The Departure (1961), in which a mezzo-soprano plays the victim of a fatal car crash. Her choral works are no less diverse, ranging from carols, including ‘Nowell! Nowell! Nowell!’, to mystic pieces like Sun, Moon and Stars.

Written by Oliver Condy, Elinor Cooper, Rebecca Franks and Jeremy Pound