In Memoriam: Krzystof Penderecki (1933-2020) Music in the Nuclear Age

by Georg Predota

Throughout his life and career, Krzystof Penderecki (1933-2020) considered music a fundamental and essential part of the human condition. He started composing when he was six, and his whole life as an artist has been a never-ending search for self- expression. One of the most versatile, multi-faceted and stylistically diverse composers of modern times, Penderecki has experimented with serialism, tonality, non-traditional means of expression and new techniques before settling on a Post-Romantic symphonic idiom. His music is a musical synthesis of “everything that has ever happened in music,” and his fertile exploration of traditional musical language has yielded highly rewarding works well into the new millennium. And it is with great sadness that we mourn the death of a composer and conductor whose music evoked religious wonder, apocalyptic terror and the tumultuous history of his native Poland. Krzystof Penderecki died after a long and serious illness in Krakow, Poland on 29 March 2020, at the age of 86.

Penderecki was born in Dębica, in southeast Poland in 1933. He quickly emerged as a force in Polish modern composition alongside such figures as Witold Lutosławski, Tadeusz Baird, Andrzej Dobrowolski and Henryk Mikołaj Górecki, composers who required players to explore terrain that pushed beyond the conventions of their instruments. Penderecki scored his international breakthrough in 1960, with a composition originally entitled “8’37.” Scored for 52 string instruments using unconventional performance techniques, it was quickly described as the most extensive elaborations on the tone cluster.

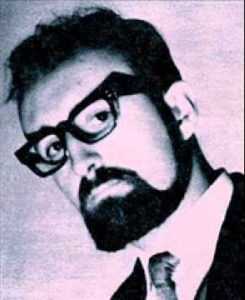

Krzystof Penderecki, 1962

When Penderecki first heard the composition in performance, he was “struck by the emotional charge of the work”, and he began to search for associations. In the end, he decided to dedicate the work to the civilian victims of the US nuclear attacks on Japan, and affixed the title Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. It continues to be considered one of the most emotional and powerful depictions of the horrors of war in the nuclear age. Penderecki kept pushing the envelope with studies in sonic timbres that essentially destroyed the classical orchestra. In fact, his visceral and other worldly sounds attracted filmmakers, and his sounds were taken over in two of the most iconic horror movies of all time, The Exorcist of 1973 and The Shining of 1980.

Penderecki remained culturally important and relevant throughout his career, and he was often considered a gateway into modern compositions. But he also realized that he had come to the end of the road, and that it was impossible to continue with this particular compositional style. Penderecki writes, “I have spent decades searching for and discovering new sounds. I had to go and find other ways to write music.” And this new style evolved from his studies of the “forms, styles and harmonies of past eras.” He returned to Gregorian chant and sixteenth-century polyphonic conventions and created a synthesis of his lifelong devotion to music and to his devout spirituality. Penderecki created a confluence of the twin threads of choral and symphonic compositions. Experimenting with an exciting fusion of ancient and modern, “his musical vocabulary is patently modern, yet its animating spirit is ancient and timeless. Much of the music seems ritualistic and potent with extra-musical meaning.”

Anne-Sophie Mutter and Krzystof Penderecki

John Paul II and Penderecki

In his music, Penderecki has confronted politics, religion, social injustice and the plight of the common man. When the trade union Solidarity formed in Poland in 1980, Penderecki composed a Lacrimosa for the unveiling of a memorial in Gdańsk to commemorate those killed in the 1970s shipyard riots. This work for soprano, orchestra and chorus later became part of another major work, the Polish Requiem, which contained music in tribute to Cardinal Wyszyński and Father Kolbe, who gave his life for another in Auschwitz. To mark the 200th birthday of Simón Bolívar, known around South America as “El Libertador,” on 24 July 1983, Penderecki composed his celebrated viola concerto. During the early stage of his career Penderecki was not writing for an audience, but as he told a historian, “I later changed my mind. Music is communication with people, because that’s the only way I can communicate easily… So I think it’s very important writing music which somebody understands.” And when a critic called him “our most skillful purveyor of anxiety, foreboding and depression,” Penderecki insisted that he was simply searching for new ways to grapple with old themes—history, faith, and human suffering.