All Music Starts From Language

Christopher Cerrone: Everything comes from language

There have been many composers who have been deeply engaged with literature. Perhaps the most famous examples are Anthony Burgess and Paul Bowles, whose novels overshadow their nevertheless formidable achievements in musical composition. While composer Christopher Cerrone has not written any original prose fiction or poetry, at least not that he’s shared with the outside world, he approaches his own musical compositions in much the same way that a writer weaves a literary narrative.

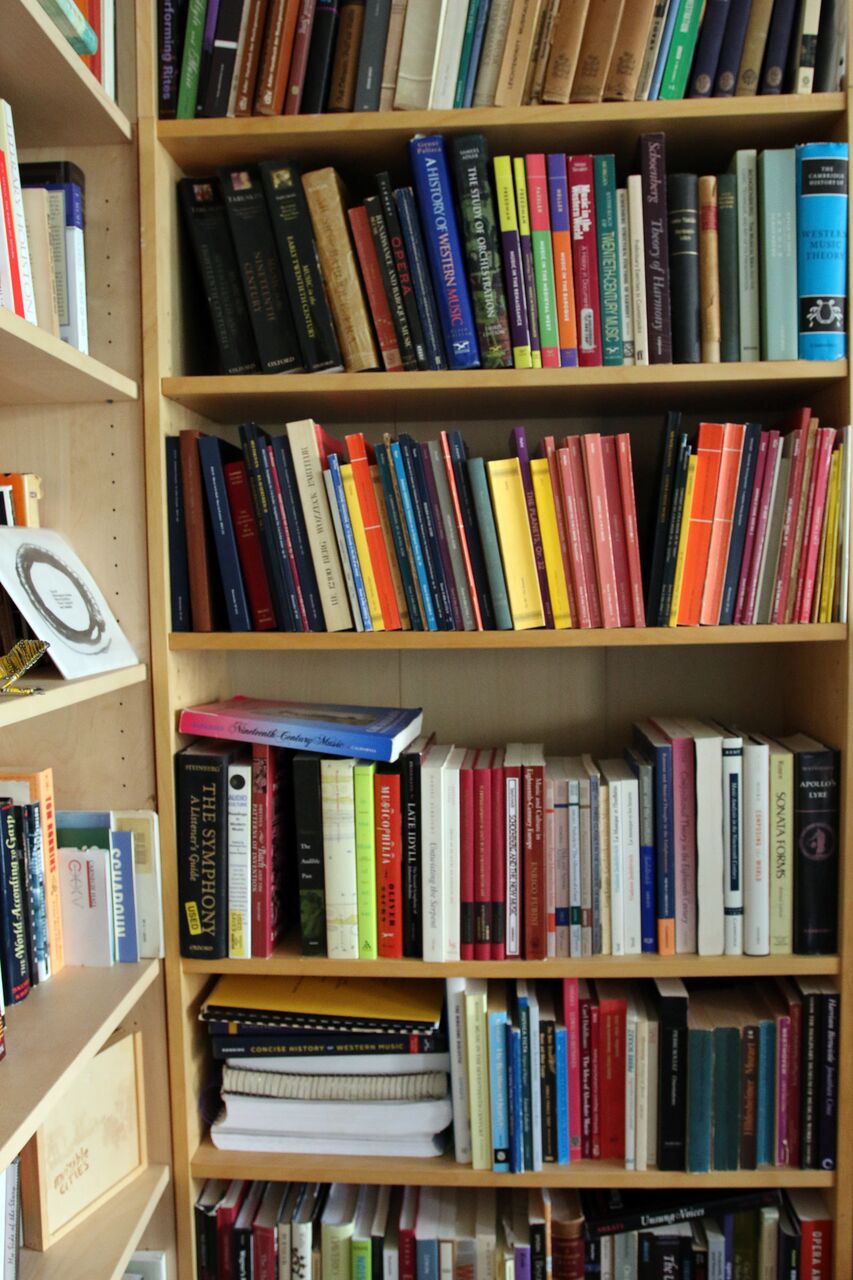

“I try to have people learn how to hear the piece via the order of events,” Cerrone explained when we visited his book-filled Brooklyn apartment. “The more it goes on, the more it’s about the memory of the thing. I lean more towards the linguistic as a composer in that I’m interested in language that’s understandable, perceptible, and followable. If I’m not following my own story musically, then it’s not interesting to me.

Aside from offering a model for his compositional syntax and aesthetics, literature is also the primary inspiration behind almost every piece of his music. In addition to the work that has garnered Cerrone his greatest amount of attention thus far—the site-specific multimedia adaptation of Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities, which was a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in Music—he has created solo and choral works derived from texts as diverse as Tao Lin, E.E. Cummings, and the 18th-century Zen Buddhist monk Ryōkan. But even the lion’s share of his instrumental output has been triggered by literary references—a stanza by Erica Jong fueled his single-movement violin concerto Still Life; a passage from a poem by Philip Larkin provided the title and something of an abstract program for High Windows, his concerto grosso for string orchestra; and a quip by Bertolt Brecht inspired his 2017 orchestral work Will There Be Singing premiered this past May by the LACO.

“It’s always so funny what comes out of texts,” Cerrone exclaimed. “The most pretentious way I ever put it is that verbosity is ontology for me. It has to be heard as words, and thought of that way, for it to exist.”

Given Cerrone’s profound empathy for language, it’s somewhat surprising that he chose music instead of literature as the outlet for his creative impulses.

“I don’t have that kind of keen observational sense or that keen psychological sense that I think really great writers have,” he acknowledged. “As much as I love words, the ability of music to have the emotional, the visceral, and immediate pre-psychological impact won out.”

Still, he makes an effort to pick up a book and read at the start of every day before he settles in to work on his musical projects.

“We all probably wish we read more, but I try to put an hour in in the morning, whatever’s going on. And the periods where I do that are the really fecund creatively for me, and they always affect how I think in a really great way. Days when I wake up and check my email and check my text messages and go on Twitter are probably less creative.”

September 27, 2017 at 1:00 p.m.

Christopher Cerrone in conversation with Frank J. Oteri

Video and photography by Molly Sheridan

Transcribed by Julia Lu

Frank J. Oteri: It seems to me that words are almost as important to you as sounds.

Christopher Cerrone: I’m a very verbal person. I grew up thinking I was going to become a writer before I decided to become a composer. I was always surrounded by books as a child, and I was read to constantly. I remember my mother used to not just read to me as a child, but also just make up stories. So I think that perceiving the world through words is just very deeply embedded inside of me, both in my music and in my notion of how music should work.

FJO: But even though you thought you’d be a writer, music ultimately won out.

CC: The genuine answer is that it became very clear to me that I had more of a talent for music than words. I loved words and I loved writing, but I wasn’t a fiction writer. I’ve noticed that my fiction-writer friends are unbelievable observers of people. It’s almost a little scary to have a fiction-writer friend, because you’re like, “When am I going to wind up in one of those stories?” I never was that kind of person. I loved reading and I loved observing things, but I don’t have that kind of keen observational sense or that keen psychological sense that I think really great writers have. At the same time, I was constantly obsessed with music, always listening and curious about what made the music work. I remember taking a music theory class in high school and thinking it made so much sense. As much as I love words, the ability of music to have the emotional, the visceral, and immediate pre-psychological impact won out.

FJO: Nicely stated. But, of course, if words are all about their meanings, and they mean specific things, how can they not provoke an emotional reaction? They’re all about being comprehensible. Whereas music isn’t, and yet it is, on another level.

CC: I remember reading somewhere that a different center of the brain processes words in song and words that are read. This kind of makes sense. One of my favorite scenes from the movie Annie Hall is when [Woody Allen]’s with that Rolling Stone reporter played by Shelly Duvall and she quotes “Just Like a Woman”: “She breaks just like a little girl.” It sounds so trite. If you listen to Dylan, your heart breaks because it’s such a beautiful song. But if you hear someone say it, it sounds dumb. So I think that combination was always what was interesting to me: the meaning of text and the meaning of words, but also the ability to process it in purely emotional terms.

FJO: The thing about music is that it gets its meaning only by the associations we attach to it. Words operate much differently. Right now we’re talking to each other and every single word we’re using is a word that each of us has said before many times and have also read and written many times, which is why we’re able to understand each other. You can’t do that with music.

CC: I think you can. I was teaching a composition lesson a couple of days ago in Michigan. I had this student who is very talented, but to me the music sounded too much like other music I’ve heard before. So I said to him that all music exists on some kind of spectrum, from something that involves nothing you’ve ever heard before to music that sounds exactly like everything you’ve ever heard before. I think all great music exists somewhere along that. In music, you’re speaking a language of things heard already. You’re just rearranging it in a way that is unique. You use sonorities that have been heard before, like I use major chords. But even if you don’t use major chords, everything is along the lines of some kind of reference.

FJO: But curiously I think that with language, and by extension literature, the spectrum is slightly different. You can’t really have something that functions in a literary way that’s completely new words that you’ve never heard before, even though the Dadaists and later experimental writers attempted this.

CC: Right.

FJO: The big revolutions that sent shockwaves through all the artistic disciplines in the 20th century are related to each other. In visual art, it was about escaping representation. And in music, it was the so-called emancipation of dissonance. In literature, the parallels to those developments would be things like stream of consciousness, automatic writing, concrete poetry. While a lot of people like to say that contemporary music didn’t catch on with a large audience because most people didn’t want to hear those dissonant sounds, those sounds are much more a part of our collective culture at this point than a novel like Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans.

CC: Yeah, it’s a rough read. I’ve not finished it. It’s so true. I think that’s interesting because it gets to the idea that works of art teach you how to experience them. My favorite works of art are works that teach you through the process of seeing them. This is what I try to do in my music through the course of forms. I try to have people learn how to hear the piece via the order of events. The more it goes on, the more it’s about the memory of the thing. So yeah, it’s funny, I think I lean more towards the linguistic as a composer in that I’m interested in language that’s understandable, perceptible, and followable. If I’m not following my own story musically, then it’s not interesting to me. Not that there can’t be moments of surprise, but the surprise is also part of the language.

FJO: Well that’s the thing. Surprise comes because if you know these chords and it suddenly goes somewhere different from progressions you’ve heard before, that gives the music an element of surprise.

CC: I also think it’s interesting to be a composer and to have grown up in an age where that’s all happened already, all the revolutions. The Berlin Wall has fallen and so has the musical Berlin Wall, so you’re sitting there and you’re like, “Okay, there is nothing I can possibly imagine that could be accomplished through just the act of radical revolution in music.” Maybe it’s possible, but to me that’s not what’s interesting. There are so many things that are built totally out of noise, out of a completely impossible to understand vocabulary—or not impossible to understand, but that wall had already been pushed up against to such a point even within the aesthetics of modernism.

People are more interested now in theater and things that are actually more familiar. I remember seeing [Helmut] Lachenmann give a lecture in New York. Apparently every time he meets some player, they’re like, “Oh, Mr. Lachenmann, hear this sound.” And it would be like krrr-krrrr-, and he’s just like, “Okay, that’s great.” Even he thought it was silly that people would walk up to him and give him new weird sounds. This isn’t what I do as an artist. I’m not just trying to make the weirdest sound possible. I’m trying to make music and art, so I think as a composer I’m much more interested in building a language that is as broad as a linguistic thing. I have so many things in my vocabulary as a composer, which are all syntheses. How much can I import into my language as a composer and still have it be consistent?

FJO: I came across a piece of yours recently which I had not before that I was floored by—the Violin Sonata. But it’s somewhat of an outlier in your output.

CC: Is it an outlier?

FJO: Well, in the most obvious way, it’s an outlier because your pieces are almost inevitably inspired by literature and have these beautiful evocative titles. Whereas calling something a violin sonata merely tells listeners about the form and instrumentation of the piece.

CC: That’s a good point. The funny thing about it is I almost feel like it’s poetic. The poetic reference of a violin sonata is what the point of that is, more than anything else. It’s obviously not a sonata in the classical sense. It has sort of a superficial resemblance to it but, to me, what was interesting about that whole thing was the idea of the poetic notion of these two people on stage playing these instruments. That’s why I called it a sonata more than anything else. I do know though that there was a concert program recently that was all my music, and I was like, “Oh, you should have included my Violin Sonata. It would have been a nice thing on that concert.” And [the person who put the concert together said], “Oh, I hate sonatas.” So I think that the piece turned off at least one person by having that title.

FJO: Wow! Yet he might have had a completely different reaction had you given the piece some beautiful, unique, evocative title, because words automatically trigger previous associations.

CC: Right.

FJO: But the words “violin sonata” also trigger associations. It gave him a very specific message, and that message was the history of every other violin sonata that’s ever been written by every other composer. And had you previously written three other pieces that you called violin sonatas and you called this the fourth, those words would immediately reference the fact that you had done this same kind of piece three times previously.

CC: I can’t even imagine that. It was definitely a one-off calling something a sonata. It was really funny, I remember my friend Timo Andres had a piece done at the New York Philharmonic, a piano concerto, and it’s just called The Blind Bannister. Apparently the New York Philharmonic insisted upon stylizing it Piano Concerto No. 3, “The Blind Bannister.”

I think most composers are a bit reticent to throw out these titles. But for me it was actually very much about the poetic notion of a sonata and writing a piece for these two people who happen to both be—more than most of the people I write for—immersed in the classical repertory in a really specific way. It’s not like it’s ironic. It just felt almost oddly romantic to call something a sonata.

FJO: I didn’t know that story about Timo’s piece; that’s really interesting. I see the title Piano Concerto No. 3, and I am immediately curious about the earlier two if I haven’t heard them yet. So, for me, giving something such a title is as much autobiographical as it is associative with previous music history. It makes you want to know the pre-history of where the composer came from for that piece, almost to the point that it can’t live independently the way a piece with a beautiful title can.

CC: I almost feel like calling a piece Violin Sonata was maybe unfair to an audience because it’s almost like me saying, “If you know all my works, you know I never give titles like this.” I don’t have a bunch of sonatas. I have literally one sonata. Since every other piece has an evocative, poetic title, you almost know that on some level that this title has a kind of layer of evocation as well. This is unfair because obviously not everyone knows all my pieces, or any of my pieces.

FJO: I tried to get to know them all over the past couple of weeks. We’ll see how far we get talking about all of them! But the other thing I thought about, before we move on from the Violin Sonata, in your notes for it you wrote that you’ve avoided calling pieces sonatas because you didn’t want to be part of that chain of influences. Your music exists outside of that, but once you give a work such a title, it forces the comparison.

CC: I felt like it was time for me, that I felt comfortable. To sort of side swipe your answer, there was this interview with Morton Feldman late in his life, and I found it to be such an interesting interview because he talks about Steve Reich. He was at that point in his life when he finally came out admitting that he sort of loves Steve Reich, but he talked about the instrumentation. I wouldn’t say it was disparaging, but Feldman’s thing was that the instrumentation is the piece. A Feldman piece might be for piano, flute, and percussion. It will have this incredible combination, and it’s so beautiful and it achieves an otherworldliness. Whereas Reich is like, “Alright, I’m finding an ensemble. It doesn’t matter. No one cares about me anyway. So there’s going to be two clarinets, and four singers, and a million percussionists, so it’s going to be amplified.”

I think that that Reich tradition is the one that I felt more comfortable in initially as a composer because of the lack of history and being able to find my own combinations. Importing ideas into more classical ensembles is something that I’ve done more lately. It’s somewhere my career has gone.

In addition to admiring Morton Feldman, Cerrone also has a great fondness for another New York School composer, John Cage, and an entire wall of his apartment is lined with framed pages of Cage scores.

FJO: There’s also the practical matter of writing for a so-called classical ensemble; these tend to be ensembles that there are many of. If you write for your own particularly created ad-hoc group, it’s possibly the only group that has that specific instrumentation and can therefore be the only group that can play the piece.

CC: That’s true.

FJO: How many ensembles are there with two clarinets and lots of percussion? By necessity, Steve Reich formed his own ensemble and worked with musicians he knew, but later in his life, he also began writing for more standard ensembles. The piece of his that won the Pulitzer, Double Sextet, is a piece for a “Pierrot plus percussion” sextet. Of course, he doubled all the parts, which is the thing he does, but it’s a standard ensemble. When people now want to put together a performance of, say, Music for 18 Musicians, they have to put a special ensemble together, whereas there are tons of “Pierrot plus percussion” ensembles out there already; Double Sextet can be played by any of them.

CC: I’m sure there’ve been a million performances of Double Sextet. On the other hand, I think he was really smart in the pieces that were for these larger combinations. He more or less wrote evening-length works. So you can justify doing Music for 18 [Musicians], because that’s the concert. If it was an eight-minute piece for the Music for 18 Musicians instrumentation, I think it would never get performed.

FJO: It’s interesting that you bring up Feldman when you talk about the Violin Sonata because, as you said, the instrumentation was the piece for him, and toward the end of his life the titles he gave pieces would just be what the instruments are.

CC: Oh yeah, like Piano, Violin, Clarinet. Well, that’s the thing I was tapping into almost with the sonata thing. It’s a poetic thing about these instruments—the poetic potential of just sound. A big part of the spectrum of where I sit as an artist is the sound thing from Feldman plus this allusive thing in literature. Get those two things together and you more or less have my music.

FJO: But the other thing about your sonata is that I think it’s very carefully not referencing other sonatas. That’s not what it’s about.

CC: No. Definitely not.

FJO: It’s about referencing the techniques required by virtuosos who play together and referencing this idea of a duo. This might have not even been a conscious thing on your part and perhaps it’s even something I inferred that isn’t even there, but the only thing that I heard in the Violin Sonata that associates it with any other music is at some point toward the middle of the end of the first movement, I heard things that sound like ‘80s power pop chords.

CC: Yeah. Totally. I always call it the Springsteen section.

FJO: Ha! How did that wind up in there?

CC: It was really funny because I remember Rachel [Lee Priday] at the premiere introduced it that way, and I thought, “Don’t say that.” But it’s so true. I think I should just own it. More and more I’m interested in bringing everything in my world as an artist into my music, and that includes pop music for sure. I grew up on a diet of it. I recently discovered the Björk album Vespertine, which is amazing and maybe my favorite now. But I had never heard it, because when I was 18, I decided I was going to become a composer, so I decided to only listen to classical music and never listen to any pop music ever again. The extremism of the 18-year old, I think, is kind of a funny, beautiful thing. But I realized I’d never heard that album because between 2002 and 2005, I didn’t listen to any pop music; I sort of just immersed myself in classical music entirely. And then I was like, “Wait a minute. This is dumb. I love all this music.” I was just being really absolutist and silly, but I have holes from that period.

Anyway, I think that for me the thing is to bring in as wide as possible a reference of things that I love. It’s not ideological. It’s just like the whole piece sets up that moment; it’s an extremely stretched out version of just three pop chords. You’ve got all these natural harmonics. They’re all sounding pitches on the violin, open string harmonics. They’re all super tonal because harmonics on the strings of an instrument that’s tuned in fifths are going to be tonal. So when you compress them all into a single moment, it just becomes one, four, and five chords. It’s literally just chords that came out of the overtone series on a violin, but I love the idea of the reference to kind of a pop song, too.

FJO: I want to unpack your decision to avoid listening to pop music in the early years of the 21st century. By then, the schism between so-called pop and so-called classical music was less pronounced. It seems like those walls were coming down, certainly in terms of what other composers were writing. So it seems weird that you were putting the walls back up.

CC: I went through a series of musical rebellions in high school. I studied piano, classically from a young age, and I played jazz. I was starting to compose, and I played electric guitar and bass. I played a lot of music of all different kinds; I was very immersed in all kinds of music. I think that there was this weird thing where I just had the ultimate rebellion into conservatism by accident, because I’d heard all this post-noise, post-rock music. I was listening to Godspeed You! Black Emperor in high school and at some point, I thought this is actually kind of like classical music. As I went further and further into long form things, I weirdly wound up back at the other end. I think it was also that I grew up on Long Island, which feels like I grew up in basically a cultural wasteland. There was no culture really at all. Capitalism fills the holes of the suburbs with more capitalism, so there was commerce and there was popular art, which I’m not denigrating at all, but there was no sort of serious visual arts because it’s a place that’s sort of cut off, other than from New York City, and it sort of relies upon New York City. It has never developed a culture of its own really, except for a few odd places here and there. So, unless you go to New York City, you don’t see orchestras, you don’t see classical music. You don’t go to museums, and you don’t see theater.

FJO: Even though the Hamptons has this big gallery scene?

CC: Yeah, I guess so. But I wasn’t sophisticated enough as a 17-year old to know about the gallery scene in the Hamptons. But I was literate. I think that’s actually why I have this great love of literature; it was the one thing you could really get deep into since you could get books. There was actually a great independent bookstore in my town which was my favorite place. Amazingly, it’s still there and it’s still an independent bookstore. Anyway, I think that the notion of becoming a classical composer was this gigantic rebellion against Long Island and the American notion of suburbia. So I think as a result of that gesture, I went really far with it. I was an insufferable, pretentious 18-year old who was like, “I only listen to Beethoven.” Then I chilled out a little bit and became a little bit less insufferable and learned to remember that I love all kinds of music.

FJO: So when you cut everything else off, were you only listening to older music?

CC: I was discovering at that point. As an 18-year old on Long Island, access to contemporary music is extremely limited. My library had a couple of Kronos Quartet CDs, so I do remember hearing the first tracks of that famous Black Angels disc. I was like, “What is this? This is so discordant.” But I think the first music I really loved was actually more like the neo-romantic tradition. I still think there are some really great pieces in that tradition. And then I discovered Lutosławski and Ligeti. What I loved about that music and what I still love about it is its mix of influences. And I discovered minimalism. Then I discovered Cage and European Modernism, and I went backwards from there. I had teachers who were encouraging me to discover more and more; that was really, really lucky.

FJO: Did you listen to music from other cultures at all?

CC: I think that was an even later thing, the period where people were just dumping stuff from hard drives onto hard drives. I think probably somewhere through the middle of college I discovered gamelan and then I discovered gagaku and West African drumming. That was all probably later in my development, but it was obviously hugely influential. I discovered American shape-note singing. It’s such an incredible tradition. It really sits with me. And I discovered Sardinian music. That moment when you could just dump anything from a hard drive onto another was an amazing moment. I mean, it also ruined the music industry, but there was a moment where you just could discover anything.

FJO: Getting back to the comparisons between how music and language function. We’re saying all these words to each other in a language we both grew up speaking and the words flow naturally without us having to consciously stop and think about each one. Certainly that happens in music when people immersed in an idiom improvise together and respond to each other’s phrases in real time. But when you’re alone writing a novel or creating a notated musical composition designed for other people to perform, there’s a lot of pre-meditation that goes into that process even though a lot of what comes out is also the result of a subconscious absorption of things you have either read or heard or both.

CC: I feel that way absolutely. I’ll come up with something and it will feel really original, and then I’ll realize it’s just a half-remembered version of something I heard 15 years ago. I think that 18-to-22 period is such an important period. I read somewhere that your brain is the most malleable at that point. It’s like a sponge, and you just absorb everything. I was genuinely very curious, but I was also very lucky to have access to a lot of stuff. I remember my teacher in college, Nils Vigeland, would give me a list every single week with 15 pieces. I’d run to the library and study everything. That was the moment for me to discover a ton of stuff. And I think all that is subconsciously in my vocabulary as a composer.

FJO: You’ve actually composed a piece that seems like an attempt to turn into musical sounds the way our brains process memories—Memory Palace.

CC: I’m surprisingly un-premeditated as a composer. I don’t plan as much as you might think. I just sort of keep going, and then I work backwards to make it seem that I planned it. That piece is for no real traditional percussion instruments. They all have to be made. So since I was stripped of the possibilities of traditional instruments, I thought I guess I better, like, think back on all the times that I didn’t really have an instrument and had 12 beer bottles left over from a party and filled them up with different amounts of water and we made a song out of it. It started as improvisation with a friend and electronics, and it just kind of went from there.

FJO: I think it really captures what you described earlier as a pre-psychological, emotive moment. But, because of the indeterminate elements you’ve put into this score, the fact that performers must make their own instruments in order to realize it, it becomes very personal and very specific to whomever is interpreting it. So I wonder how divergent performances have been and how representative you feel they have all been of your intentions.

CC: How do I put this? There’s a moment when pieces stop being something you wrote almost and they start to become part of the repertoire. That is the most amazing feeling, but it’s a very strange feeling when you see something so far from where you conceived it. It’s a surprisingly fixed piece in terms of the pitch choices being notated, but I think that the sounds, the colors, are the most interesting part—the timbres. I remember one person, his house was being demolished. He moved and he saved all the wood from his deck and took the wood for that piece out of it. That’s so cool. And I was at this party recently, and this guy I happened to have corresponded with, whose son is a percussionist, came up to me and said, “I want to thank you. My son played Memory Palace and we made the instruments together. We don’t really have that kind of relationship. But since he had to do it, I helped him and it was this really big bonding experience.” That is probably one of the more meaningful things that anyone has ever said to me about my music.

FJO: That’s beautiful.

CC: It’s something I’m sure I’d do with my own dad, although we argue when we build things together. [The electronic component of] that piece literally had a set of wind chimes I recorded that are in my parents’ house still. I was digging really deep with that piece. I think that that’s been the process for me as an artist, generally speaking. The thing that’s really hard is to emotionally strip yourself down to exposed places, but that will yield something powerful.

FJO: Interestingly, the two pieces we talked about in detail so far, the Violin Sonata and Memory Palace, are both very much about you having an idea and then running with it. Those ideas were not things you got from somewhere else, although as we’ve been saying, nothing exists independently; everything comes from something. Still, you had no guide to take you on a path; whereas, with the majority of the pieces you’ve written—obviously all of your vocal pieces but even many of the instrumental ones—the inspiration will come from something that is concrete that already had existed in literature, whether it’s a novel or a set of poems. So I’m wondering, in terms of what you just said about stripping yourself down emotionally to find this essence, how do you work within something that already exists to find the thing that’s you?

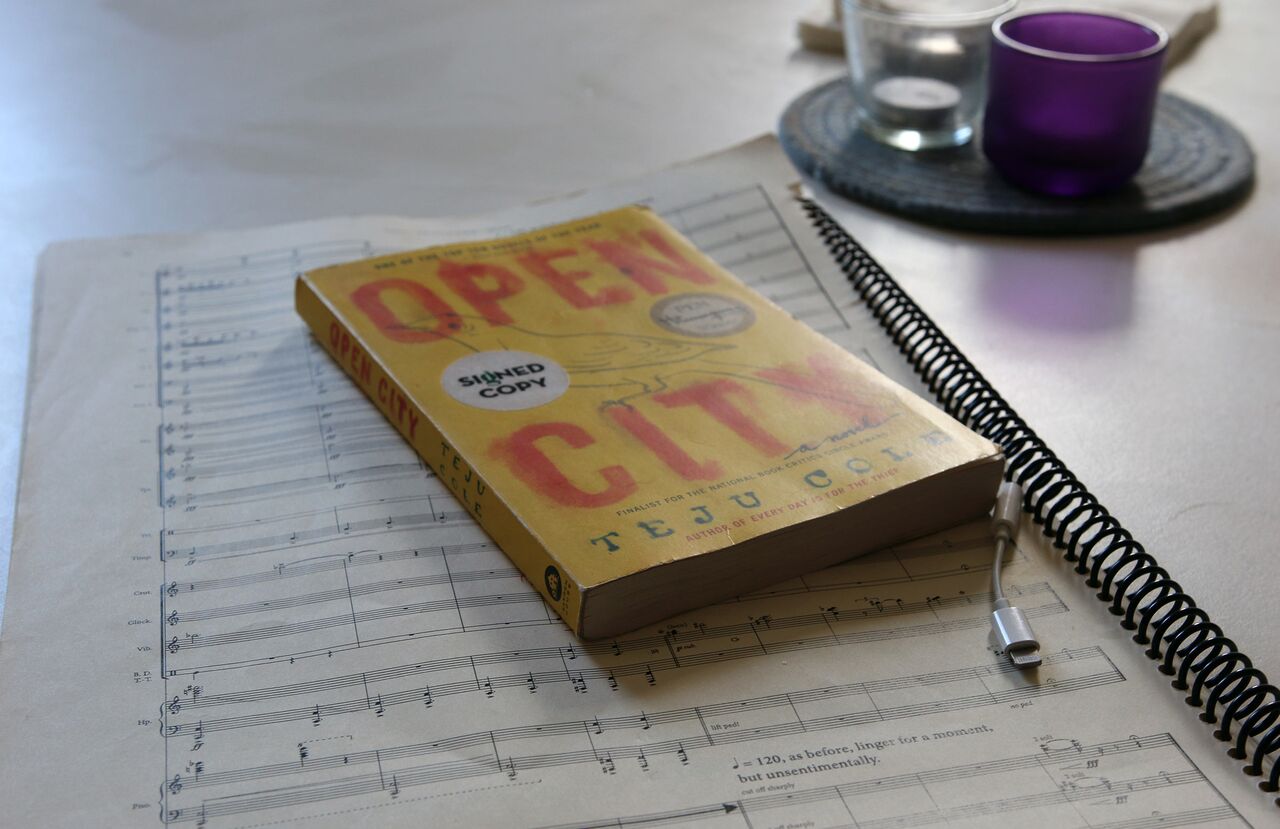

CC: I think it’s as simple as the way you read a book and you relate to it. You don’t have to be like that person to relate to it. I’m reading this book by Teju Cole right now, and he’s a Nigerian-American writing about his experiences. Obviously that’s not an experience I relate to, but I still relate to the book. And I still relate to the things he says and does in the book. I think that’s true of most of the texts I’ve dealt with. I’m sure I have a very different experience than most of the writers I set. You can still relate to them, and they become about you anyway. People have commented on how my interpretation of works tends to become about me. It becomes about how I feel when I read something, and so I think it’s the same kind of emotional thing. It’s just filtered through someone else’s text.

FJO: So I want to dig deeper into reading and its importance for you—how much you read, where you read, what you read, how you find things to read, and when that moment comes and you start pondering whether or not you can turn it into a piece of your music.

CC: I try to read in the mornings, as much as I can, but it varies, honestly. We all probably wish we read more, but I try to put an hour in in the morning, whatever’s going on. And the periods where I do that are the really fecund creatively for me, and they always affect how I think in a really great way. Days when I wake up and check my email and check my text messages and go on Twitter are probably less creative. People usually recommend things to me, and I’m always lucky to either hear someone or, as I’ve had some really great experiences of late in different residencies, literally meet the author, get to know the works of my author friends. I have a lot of very literate friends, and I grew up in a family that reads a lot.

Starting from there and then outward, it’s always just some sort of random connection. Some people say it’s so much easier to write a piece based on a text because you have that guide structurally and that’s half true. But the part they don’t talk about is the volume one goes through to find a source text. The research aspect of it is insane. For every poem I set, I read 500 poems. This one is too long, or this one doesn’t quite get the feeling right.

FJO: So what’s the “Aha!” moment when you’re reading something? Is it the very first reading and you’ll say, “Oh, this really grabs me. I hear things in my head; I hear sound.” Or will you come back to something after reading it a few times and internalizing it, and then decide you can do something with it?

CC: More often than not, it’s usually pretty immediate. When you read a poem and you’re like, “Oh, okay, clearly.” And it’s usually the length. “This is short. Great.“ So that’s often the “Aha!” moment.

FJO: Like those peculiar Bill Knott poems you set, which I knew nothing about before I heard your Naomi Songs, even though Knott had posted them all online. How did you discover his writing?

CC: I have this friend who’s the most crazily literary person and he dumped a ton of stuff on my hard drive that he found on the internet. Those Knott poems are so great, right? I found them, and he died a year later, and it was like, “Oh God, how am I going to get the rights to these? Who even executes his estate?” But I found the person who had written his obituary in The New Yorker and he managed to put me in touch with his executor, and he was super nice about it. Then there are certain authors. For example I love Lydia Davis, but I feel that so many composers have done such brilliant things—David Lang, Kate Soper. There are just all these great pieces with Lydia Davis texts. I don’t need to be the fifth person to write one. She’s brilliant and great, but there’s something about the discovery; one hopes that in the world that we’re in, the texts I use are often discoveries for people.

FJO: I remember when I first learned about Lydia Davis. I was the music person on a multi-disciplinary panel many years back, and the literary person on that panel was trashing the short stories of Lydia Davis because they’re way too short and undeveloped. This person seemed to treasure long, dense work. But that negative reaction actually made me want to seek out her work and read it, and when I did I instantly fell in love with it, too. At that point, nobody in the music community seemed to know who she was, and in the back of my head I thought it would be really cool for her writing to be set to music. Then everybody else did it!

CC: Poor Lydia probably gets these emails every week: “Can I use your text?” I learned about Lydia Davis because I heard Kate Soper’s piece, and I thought, “Oh my God, this writing’s amazing.” But maybe since I had my moment with that already through music, it was less interesting to me to try to do the thing again.

FJO: Then why Italo Calvino?

CC: Yeah, he’s well known.

FJO: Very well known, definitely not a discovery. And yet his writing inspired several pieces of yours. Most obviously Invisible Cities, your weird, wacky, magical, wonderful piece that’s more than a setting of this pre-existing thing, but which was obviously inspired by it.

CC: Calvino to me is so inspiring as an artist, and I think he was the person who helped me discover how to become the composer I wanted to be, much more than any composer. He’s such an amazing writer obviously, and I read quite a few of his books. Some were funny or cute. Well, not cute. That’s the wrong word. He would have hated that. But they have a lightness to them. He loved the word lightness and talked about the word lightness a lot. Invisible Cities had that, but it also had a little bit more depth and a little more emotion to me. It read very emotional to me. I don’t know if others read it that way.

I cared and still do care about structure so much—interesting, complicated structures. But I’m also interested in writing music that hopefully people think is beautiful and sensuous and lyrical. So I read that book, and I thought to myself that this is a writer who can accomplish lyricism and also complexity, but not how complexity has come to mean unpleasant somehow. Not that people actually think that, but I think there is this sort of subconscious subtext with difficulty.

To me, Calvino’s not difficult. He’s complicated and complex, but he’s not difficult. To me, he’s effortless, and giving the illusion of effortlessness was so important. So I read his books, and I’m like, “This is what I want to do as a composer.” It was such a moment for me. And so I definitely wanted to make things out of his amazing works.

FJO: So the idea of doing a piece that’s experiential, that sort of breaks the fourth wall and takes place in multiple locations, breaking the space-time-proscenium continuum of how we experience music theater pieces, where in the process of creating this did that become how it was going to be done?

CC: Well, I was writing this piece obviously through grad school, and I didn’t really know what it was going to be in a sense. I knew that the text was sort of the anchor. The text is all based directly from the novel. But I knew that this was not an opera in the sense of we’re going to go ahead and tell a traditional story. This was a piece that is a meditation. And I knew it needed something very, very unconventional.

I had applied for the VOX Workshop at New York City Opera, and it was accepted into it. That’s where I met Yuval Sharon and we became friends. We did this workshop, and that was the culmination of me realizing what it was. It was originally scored for orchestra and it had all these opera singers, and it was just not right. I knew there was something there and I kept going with it, but I knew that the version of the piece was not the right version at all. So I pared it down to a chamber ensemble—a sort of unusual chamber ensemble in the Reich tradition of having multiple pianos and percussion in the group. And it sort of kept going and I still didn’t know what it was. I had this workshop at this thing called the Yale Institute of Music Theater; Beth Morrison was producing it at the time. She literally said something along the lines of “I don’t know who would be the right person to direct this. It would have to be someone with a crazy, out-there vision. Maybe someone like Yuval.” It was really funny. I’m like, “Well, that would be great.” And so when he moved out to L.A. and he called me, I had come to the conclusion that this should not be a staged piece. It should have people all over the place, all over throughout the hall. It was going to be amplified, and it was going to have movement, and that’s all I had at that point.

So Yuval comes to me with this idea, “What if we do it in the train station with movement and using headphones so you can hear everything perfectly, but the experience is flexible?” I think I said yes immediately. Then I can do all the sound design stuff too, and I can have all sorts of crazy amplification ideas. That’s where my work was going already anyway. The idea of the train station was entirely his, but it seemed perfect. I think it was actually sort of at the behest of Chad Smith from the L.A. Phil. They had done the overture and Yuval was sort of casting around what to do, and Chad suggested what about this piece. And Yuval’s like, “Of course, I know this piece from VOX.” And it was kismet!

FJO: You mentioned sound design, which is interesting given your years of avoiding listening to pop music. After all, so much of what pop music recordings are about is their sound design, whereas people whose work comes out of the so-called classical music tradition rarely think in terms of shaping recorded sound objects and bringing certain things out in the studio.

CC: Something that was revelatory for me was that when I went to graduate school, I was randomly assigned to work in the recording studio. I didn’t really know anything about electronic music at that time. I got a C in electronic music in college. It was my only C and was sort of a badge of honor. But then I started working with microphones, and that was the moment where everything started to spill back into my life in terms of technology. I got really interested in technology and sound design. I realized that I sort of hate how classical music has been recorded, one mic 50 feet away from the orchestra, no EQ-ing, incredibly loud and incredibly quiet at different times. That was the moment where we started doing Invisible Cities. So I’m working with Nick Tipp, our sound designer, and I was like, “Oh, let’s compress this and let’s have these really quiet moments be really loud.” There’s whispering, and the whispering’s super loud. I got to make a studio album live, and it was incredible to me. Actually learning how to do it was incredibly important.

FJO: That surrealness of loud whispers mirrors the surrealism of Calvino.

CC: Absolutely.

FJO: So you were able to put your own stamp on it, but that text is what guided you.

CC: Yeah, 100 percent. Everything in the opera comes out of the book.

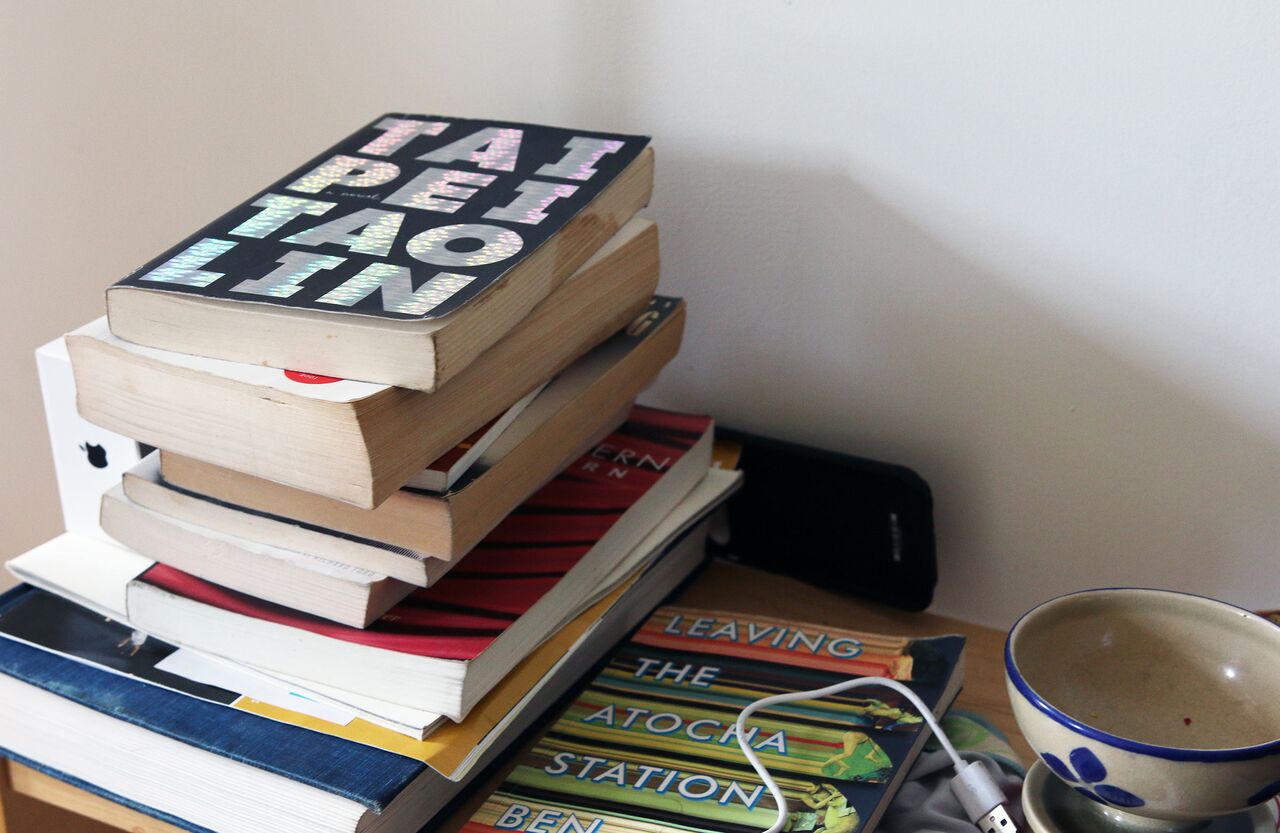

FJO: So what happens when you set a writer who is completely different, like Tao Lin, whose poems are the basis for your song cycle I Will Learn To Love A Person? Or maybe in your opinion, he’s not so different.

CC: He could not be more different.

FJO: Yet his words speak to you as well, and they’ve brought out music from you.

CC: I spent more or less three years in and out working on that opera. My identity was formed around it as an artist and as a composer. So for the next vocal piece—it was literally the next, it was the first vocal piece I wrote after that—I was like, “Okay, I love Calvino; he’s a genius. But I need the complete opposite now.” Calvino is semi-contemporary; the book is from the ‘70s. But I wanted to do something written, like, last year. I’ve noticed that whenever composers set texts, they always tend to refer to something much older. If they’re not setting Auden or Whitman, they’re setting 20 or 30-year old things. I didn’t really know anything about contemporary poetry, and so I sort of dove in.

I had this friend of a friend who was a poet. She’d written this article about this movement called the New Sincerity. I think the term New Sincerity came out of this David Foster Wallace article called “E Unibus Pluram.” It’s the opposite of E pluribus unum. He was talking about irony and postmodernism and how television absorbs it. I think he was very ahead of his time in that regard. I see the internet as the same thing. TV was not a big deal compared to how crazy the internet is in our culture. The final rebels will be ones who dare “single-entendre principles.” I love that quote so much. That was where that movement sort of took its “Invictus” from. I was very interested in that movement, because it was something I was really relating to at that time in my life, writing music that does not have a sheen of a postmodern irony around it. I wanted something that was very direct. So my friend Jen Moore wrote an article on two poets, Matt Hart and Tao Lin. And I saw these Tao Lin poems and I was like, “Oh, this is perfect.” They’re basically song lyrics. Sometimes people struggle with the tone of his poems, which is very hard to pin down—sort of ironic, but also funny, sweet, and sensitive. There is this one poem, which I love and I almost set. I decided against it. The last line is “I AM FUCKED,” existentially in capital letters, 43 times in a row. I loved how Tao Lin was just really direct and really honest. I loved how he exposed himself in those poems emotionally, so I thought isn’t this kind of wildly rebellious to have a song cycle where people actually discuss deep-seated fears and pains, but not in a sophisticated way. Just like, “I am this.”

FJO: I know his novels more than I know his poetry. His novels are so twisted.

CC: Oh, like Eeeee Eee Eeee…

FJO: My favorite one is Richard Yates, which appropriates names of teen stars for its main characters but isn’t actually about them.

CC: Oh yeah, Dakota Fanning.

FJO: And Haley Joel Osment. The whole novel is basically a G-chat between these two characters whose names seem to just be there for the sake of irony. Because of that, I find it somewhat incongruous that he gets lumped in with the New Sincerity. To me his novels seem completely ironic.

CC: I would say that that’s somewhat true. Taipei, his most recent book, is, I think, the closest to being emotionally direct.

FJO: I haven’t read that one yet.

CC: It’s super good.

FJO: But another one of his novels, Shoplifting from American Apparel, is also super ironic.

CC: Yeah, definitely, I think he’s still grappling with irony. I think everyone’s grappling with irony all the time. The poems are the most direct thing he wound up writing.

FJO: You mentioned David Foster Wallace and I see Infinite Jest on your bookshelf. That one’s hard to hide because it’s so huge. But you’ve not set him.

CC: There are tons of writers I love who I did not set. They tend to be verbose. And they feel complete. I don’t think there’s anything you can do. The thing about writers that I set is that there has to be room in the text for more. Another poet who I feel that way about, and he’s one of my favorite poets, is Frank O’Hara. I don’t know if there’s anything you could do to a Frank O’Hara poem that would make it any better than what it is. It feels complete; everything’s there. So I wouldn’t want to set his poetry, even though I love it, you know.

FJO: And besides, if you were setting David Foster Wallace, what would be the musical equivalent of a footnote?

CC: We’ll come back to this later!

FJO: Literature has obviously been key to the pieces of yours that have texts, but it has even informed many of your completely instrumental pieces like High Windows, the gorgeous string orchestra piece you wrote for the String Orchestra of Brooklyn, which you named after a line from a poem by Philip Larkin. How did that play out? Did you read the poem and decide that, instead of setting it, it would influence you musically in other ways?

CC: Usually there’s some kind of synchrony. Titles come at all different points in the composition process. Sometimes it’s like, “Bam, that’s it.” Then sometimes it’s like, “This was what I was doing.” That is often an equally powerful thing to me. And sometimes you’re just desperate and you really need a title. Usually it’s pretty rare that I have a really clear premeditated notion of what I’m doing when I’m starting a piece. Usually it finds itself over the course of a piece.

FJO: So how did the title come about for Will There Be Singing, particularly leaving off the question mark?

CC: That was really funny. I remember I got a number of questions about that. Is there a question mark? And I’m like, no. “Will there be singing.” Not, “will there be singing?”

FJO: But that also comes from somewhere—from Bertolt Brecht, though obviously in translation. Although he’s the guy who also came up with the line “Is here no telephone?” in English for Mahagonny.

CC: And “Oh, don’t ask why.”

FJO: I think there’s a question mark in Brecht’s original.

CC: Yeah, and I think the Brecht line is actually: “Will there also be singing?”

FJO: It’s interesting that the source was Brecht, since it’s essentially making a political statement about our time. There’s a famous anecdote about Brecht in East Germany after the war. He’d written plays that were censored and couldn’t be staged, and someone from the West interviewed him about it and asked, “Since you’ve always been a force for freedom of expression, how can you live in this society where they’re censoring your work? “ And he said, “Well, that means they read it!”

CC: Oh, Brecht. So clever.

FJO: So what’s the actual story with the title?

CC: That one was pretty clear from the beginning. I started writing that piece in January 2017 when the world felt like it had fallen apart. I knew that quote and I emailed it to Martin Bresnick the day after the election. This has to be the mantra. It was really funny because this is also how I know Yuval and I are artistic soul mates: he was obsessed with the same quote, and sent out something about that quote in a newsletter with The Industry. So we’re clearly in the same zone.

The piece starts with chords that are me feeling anxiety about the world. They are just harsh chords and it goes from there. But it doesn’t feel like a political statement because I don’t know if I’m interested in making political statements. If you haven’t made your mind up about Donald Trump, I don’t think my orchestra piece is going to convince you one way or the other. It’s more just a reflection of the times that we’re in and who I am as a person at this moment.

FJO: It’s now almost nine months later and the world still feels like it’s falling apart, but it does seem like there will still be singing no matter what.

CC: Seems that way. I’m starting this new piece right now. It’s always so funny what comes out of texts. The most pretentious way I ever put it is that verbosity is ontology for me. It has to be heard as words, and thought of that way, for it to exist. There’s an inscription that was an epigraph to another book of poems by this writer John K. Samson by this guy named Tom Wayman: “Weak things have power.” Democracy can only exist when we are weak, when we are fragile, because then we want it to be democracy and not autocracy. It’s something I’ve been really connected with lately. What is the opposite of Donald Trump? It’s someone who admits their fragility. This is a person who can’t ever admit fragility, and the response to any kind of thing is anger. In a sense, while I deeply empathize with the anger of so many people in the world right now against him, admitting your own fragility as a person is the political statement that I want to make. I’m a flawed person, and I want to express it. I have fears. I have anxieties and I have pain. That, to me, is the way forward. The way forward is not people screaming at each other.