Why Sir András Schiff is unfair to modern audiences

by Frances Wilson

A Response to Sir András Schiff’s Comment About Modern Audiences

The attitude and behaviour of classical music audiences has been in the British news (not for the first time!) thanks to an article about Hungarian pianist Sir András Schiff in advance of the publication of his memoirs. In one section, he writes a letter, as if to Robert Schumann, decrying the parlous state of audiences today:

“….the quality and general culture of audiences has diminished in equal measure……The average listener of today has hardly the faintest idea about what he is hearing. He neither knows anything about new music, nor can he differentiate between outstanding, moderately good and poor performances.”

Sir András Schiff (source: The Telegraph (UK), 8 March 2020)

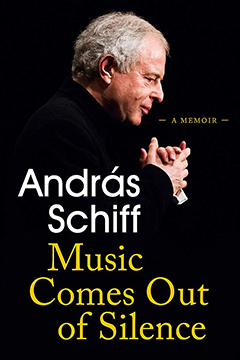

Memoir of Sir András Schiff © Amazon

I do think András Schiff is being rather unfair to audiences. And why? Because there’s a very simple equation here: without an audience, the musician/s does not have a concert (nor a fee). He/she/they may be performing to a handful of people or a full house at Carnegie Hall, but the audience is a crucial part of the concert experience. Without an audience, you are just playing into the void (sadly, some musicians are finding this is a necessity as concert halls close due to the coronavirus outbreak, but that’s another story).

Of course audiences do more than simply pay for tickets and supply “bums on seats” – though the revenue from ticket sales and “value-added” income from the sale of food and beverages, programmes and other merchandise, and advertising at the concert venue cannot be underestimated; all these things enable a venue to function and pay its staff and artists. But audiences do something else at a concert: their mere presence alters the acoustic of the hall, and they also help to create atmosphere (see above about playing into a void). Most musicians will tell you that they actively enjoy performing to an audience and that the sense of communication between music, musician and audience is paramount to the shared experience of a concert. When that communication is very powerful, amazing things happen: the audience may fall completely silent, as if holding their collective breath; or they may burst into spontaneous applause between the movements of a work (something else Sir András has an issue with….!). Sometimes, at the end of a particularly moving or absorbing performance, one has the sense of release, a joint sigh as the audience relaxes and reflects on what has taken place. For the performer, the sense of the audience listening intently is palpable and can inspire a performance to really take flight. These are very powerful moments in live performance and demonstrate how remarkable music is in creating communication without words.

This leads on to András Schiff’s comment that today’s audiences are not sufficiently knowledgeable or discerning to tell if the performance is exceptional or mediocre. In fact -and because of the magical unspoken acts as described above – audiences can certainly sense the quality of a performance, even if they cannot explain it in high falutin language. Once again music, and its transmission by the musician, reveals its power to communicate!

Sadly, András Schiff’s comments revive – yet again! – that tedious notion that you need specialist knowledge or a certain level of education to enjoy, or better still appreciate classical music. The truth is, you don’t. All you need are your ears and a willingness and curiosity to submit to the sounds, to the experience, the flow of the music and the emotions it provokes. There’s no right or wrong way to enjoy the experience, and there’s no test at the end of the concert to see if you “understood it”, no exam in musical analysis to check if you know what Sonata Form is or the meaning of Allegro Amabile (“smile as you quickly play”). The majority of audience members are there not to show off their specialist knowledge, but because they enjoy the experience of live music.

It’s important to respect the audience, for they buy the tickets and without them, there wouldn’t be the same opportunities to perform. This is especially true for less well-known musicians who are trying to make a living playing for local music societies and regional arts organisations, where the ability to pay the artist a fee is predicated almost entirely on ticket sales.

Patronising attitudes towards audiences, and potential audiences, don’t really help an artform which is constantly trying to attract as wide an audience demographic as possible, and serve to reinforce the notion that classical music is “elitist”.

Let’s stop behaving as if classical music is for the few, not the many; that it’s some kind of precious crystal that only a select minority can see and engage with. Instead, let’s endeavour to make everyone feel welcome at concerts, regardless of their credentials or knowledge.