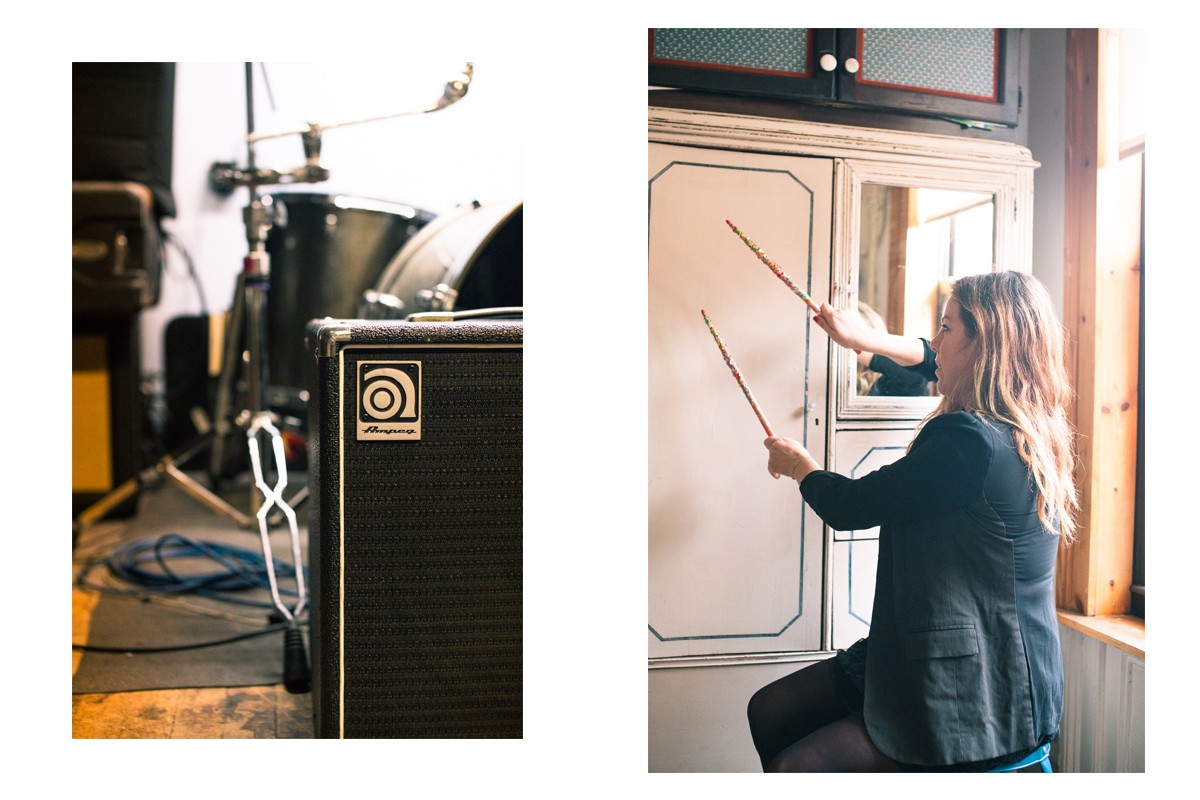

Why aren’t there more female drummers?

Culturally we’ve idolized talented performers since long before the music industry was perceived as a highway to monetary gain, fame and luxury.

Before Rihanna, Beyonce or Taylor Swift dominated charts there were women like Ma Rainey, Joni Mitchell, Ella Fitzgerald, Pauline Viardot and more. Despite sexism, racism, poverty and a host of other troubles, this bygone generation used their voice and talent to make a lasting impact on history.

Today a new generation of singers and entertainers is shaping youth culture with brash, inglorious lyrics that celebrate individuality and mastery over fate. But something is still missing; something that a sassy slow wine from Rihanna or a fluff-and-sparkle-laden guitar solo from Taylor Swift can’t fix. We’re so focused on the one-in-a-million Mariah Carey success story that we tend to forget the path for other women in less visible industry positions is just as difficult – and that often, the end of the road holds much less glory.

As of 2013, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that a mere 26.9% of women made it to the level of professional musician. In 2015, another study showed that only 5% of recognized producers were women and that only three solo women artists had won the prized Mercury Award over the course of its 22 year history.

The longterm impact of gender socialization and the musical genres often associated with drumming have made growth especially difficult for female percussionists. So much so, that even though the number of women pursuing percussion at the collegiate level has incrementally risen since the 1970s, the number of women percussion professors, instructors and even professional orchestra members has remained nearly the same.

Unfortunately, the music industry reflects this sluggish rate of growth. Drummer and founder of Tom Tom Magazine, Mindy Abovitz, started the publication to spark progress in this area.

“It started in 2009, when I realized that I knew more than Google about the female drumming community,” she explains. “I Google-searched the phrase “girl drummer” and the only results that came up were stuff like, “can women even play” or “do girls play drums?” That’s when it really hit me that things like Google and Wikipedia had no onus for information. They say it’s “democratic” or “aggregated” information but if you find out whose putting Wikipedia together, well, four or five years ago the majority of those people where white males.”

“If you go even further it’s white males with access to computers who like to code and can speak English,” she elaborates. “If those are the people writing the information, who are they going to leave out? Who are they going to misrepresent? For Google it’s the same: the things that pop up first are from the people who can get the best search results, who are the best at SEO, categorizing and tagging. I considered myself to be beyond the knowledge of those information sources, so with Tom Tom I set out to make myself an expert. I try to find out about women drummers, to research and connect with them so that Google, the internet and the world knows we exist.

Abovitz’s own drumming career got a late start. She picked up percussion in her early 20s while attending college in Gainesville, Florida. As a teen growing up in South Florida she had an early interlude with the bass guitar, after receiving one as a gift from her older brother. Around the same time, Abovitz became active in the local punk scene, frequently traveling to Miami to attend shows and concerts. It was a male-dominated space but Abovitz loved the music and saw few other options, until she discovered the Riot Grrrl movement.

“Simultaneous to this punk movement there was this up-cropping of women in bands,” she says. “Those girls were about 10 years older than me back then, and so they became instant role models. These were women – some of them didn’t even know how to play their instruments – who didn’t give a fuck. They were really loud, really unapologetic and really political. They had these lyrics and mottos and zines I could get behind. You know, things like, “girls to the front” – the language was just really empowering.”

Bands like Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy and Red Aunts became the lens through which she viewed her world. She adopted their politics, their belief systems and their determination to rebel against a system riddled with sexism.

By the time Abovitz started college in Gainesville, she knew she wanted be part of the town’s thriving local music scene, and at 21 she was handling bookings for two local venues. Her friends were all musicians and most of them were male, though she makes sure to stress that her female friends were equally as political and creative without instruments.

They were also supportive: When Abovitz showed interest in drumming, her best friend surprised her with a drum kit for her birthday. Shortly after, the two started a band with three more friends; they were all women and none of them had every played their chosen instrument before. The lack of rehearsals and novice-level skill didn’t stop Abovitz from promptly booking them a show at a local venue.

A year later, the budding musician set down roots in New York and once again involved herself in the music scene. By the age of 29 she was working at East Village radio, where she noticed a zeitgeist change that echoed her teenage years. “There was a resurgence of the Riot Grrrl movement, and it was at that point that I realized things weren’t really changing for women and girls in the music industry.” For Abovitz, confronting the stagnation was a difficult moment.

“It made me feel as if we were heading back in time and not forward,” she explains. “As a teenager, that movement was an anchor; it helped me grow and moved me forward. Having it come back around in my thirties gave me anxiety. It made me feel like, if we only have this, if girl musicians are reaching to this thing that happened in the past to help them be in the present then maybe we’ve done something wrong. Maybe I haven’t done my job.”

She had spent her teenage years thinking about the politics behind the lyrics of her Riot Grrrl idols; she’d spent her twenties being a musician, and as her thirties approached she increasingly felt it was her duty to help shift the narrative for the women who would come after her.

“I took for granted that I’d built this Utopian world of female musicians who we were really adept at their instruments around me,” she says. “The world I created was not the world that people knew, and it was becoming more and more obvious to me… I felt that there was this divide.”

Just as impulsively as she’d prematurely booked her bands first show in Gainesville, Abovitz started Tom Tom. She enlisted drummers, producers and beat-makers as her writers and editors, and tapped several musicians to became her “brain trust.” Together, they started to unpack the question at the heart of many of Abovitz’s concerns: where were the women percussionists and how could they support each other?

“Sometimes it still feels like I’m screaming into a hollow tunnel,” she admits. However, she hasn’t been completely without victories, either. Abovitz has cultivated a sense of community and a camaraderie that transcends the initial wariness some women percussionists felt toward each other. “There was one woman who didn’t want to be in the magazine when I first approached her, because she was used to being the Queen B… Slowly, over time, I feel like everyone who has participated in the events or been remotely involved in the magazine now feels that we have each other’s back. It’s grown into a space to elevate each other and help get each other jobs.”

When Abovitz broaches the subject of work, it becomes clear that the scarcity of jobs is yet another factor women percussionists must deal with. If being a musician is already hard, being one of the few woman playing a particular instrument is potentially even harder.

“It’s not so much people are reluctant to hire women,” Abovitz explains, “it’s more like they see us as an anomaly. There’s this really great Aziz Ansari skit in his show Master of None, where he and his friend, who is also Indian, go to audition to be on this Friends episode. He accidentally gets cc’d on an email with the producers and they basically say they can’t have two brown people in one episode. … [S]omething similar happens when you’re female drummer, it’s almost like you’re filling a quota. There are certain musicians who only want female musicians behind them, sometimes for the right reasons, sometimes as a gimmick.”

Abovitz can recount plenty of stories about women drummers being taken off jobs because male band members refused to tour with a woman. Sometimes, it’s even the men’s partners that interfere. “One of my drummers called me and said that her tour was about to leave … [when] the manager of the guy’s band said that they would have to rent a separate car, pay for their own gas and drive themselves around the country. All because the guys’ wives were afraid of what might happen if they shared a van with women,” she says.

“Prior to starting Tom Tom I was also a female drummer in the industry and I understand how frustrating it can be. I was like a foot solider then. Now I’m the person who is talking about sexism and inclusion the loudest,” she says. “I’ve definitely put myself in sexism’s way – I hear about it all the time because I’ve invited it into my life by talking about it, by hearing people’s stories about it and by becoming media around it that cares about expelling it.”

For Abovitz, pushing female drummers forward means getting them meaningful jobs and boosting their profiles. “We try to be a hype machine for female drummers, to legitimize them in the world’s eyes,” she explains. “Once we gain legitimacy … the industry will just look at us as drummers, and not as ‘female drummers’.”

By Stephanie Smith-Strickland, Via