What’s the Deal with Do Re Mi? The Story of Solfège

One of the more enduring moments from The Sound of Music comes when a free-spirited Maria von Trapp (Julie Andrews) takes a handful of giddy Austrian children out for a singing rampage through Salzburg, Austria.

It’s fair to say that “Do-Re-Mi” is etched into the pop culture mind — you probably knew it before you took your first music class. But the origins of those syllables predate Rodgers and Hammerstein, and aren’t arbitrary sounds. To find out where they came from, we talked to Associate Dean and Professor of Musicology Andrew Dell’Antonio of the University of Texas at Austin’s Butler School of Music.

Assigning a specific syllable to a corresponding note is the foundation of a pedagogical system called solmization. Found in musical cultures all over the world, the form most associated with western European music is known as solfège (or solfeggio, if you’re feeling especially Italian). The name solfège is self-referential — sol and fa are two of the syllables found in that pattern: do-re-me-fa-sol-la-ti.

Guido d’Arezzo (ca. 991–after 1033), the monk to whom we attribute the beginnings of staff notation as we understand it today, also gets credit for solfège. His choice of syllables is a mnemonic for a particular chant, a hymn to St. John the Baptist called Ut queant laxis, each corresponding to the initial sound that kicks off the separate musical phrases in the first stanza (except the last, si, which was added centuries later and is a contraction of two sounds found in the last line — but we’ll get to that):

Ut queant laxis

resonare fibris

Mira gestorum

famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti

labii reatum,

Sancte Iohannes.

The matching syllables are only part of what makes this so clever. “The beginning of every phrase starts with one step higher than what we use as a scale at the time,” explained Dell’Antonio. “So the first note of the chant begins on one particular note, and then the next phrase begins on one note up, and then the next phrase one note up.”

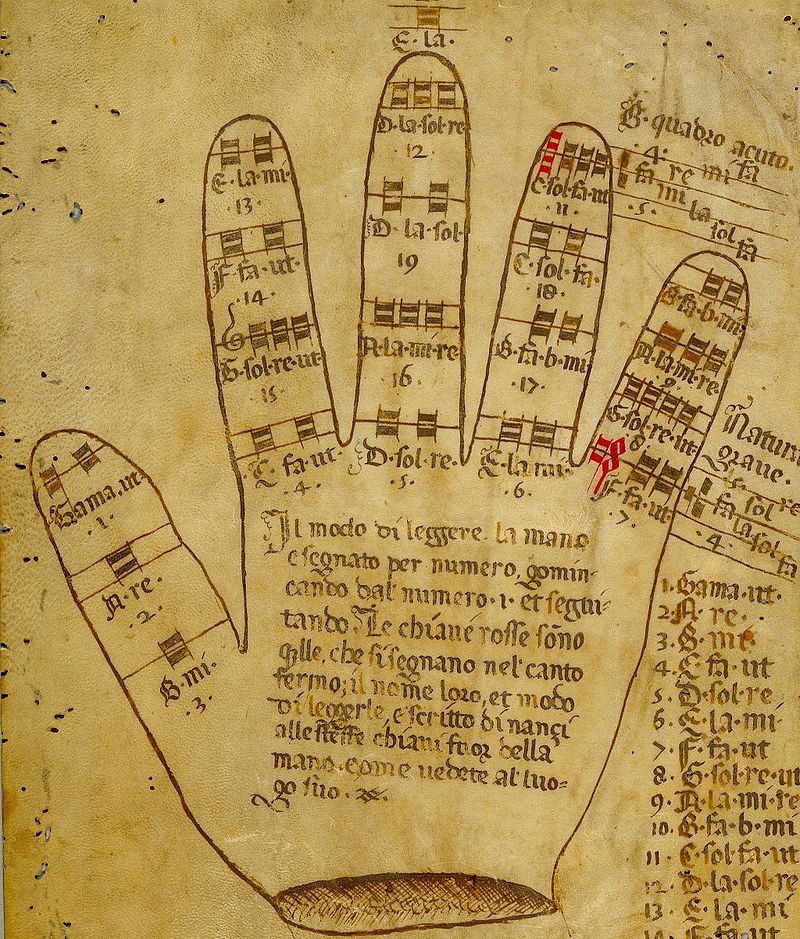

When Guido codified those syllables (without that final si) it created a six-note series called a hexachord, defined by the relationships of the intervals from one note to the next (in this case, whole step – whole step – half step – whole step – whole step). Also worth noting is that Guido assigned each note a letter name. Ut got the Greek letter “Γ” (gamma), re was “a”, mi “b”, fa “c”, sol “d” and la “e.” And there’s a reason why our monkish friend started with Γ: “It goes back to Greek notions of completeness,” said Dell’Antonio. Hence gamma-ut, or the gamut, neatly defined by Britannica as the “full range of pitches in a musical system.” The whole business of hexachords was mapped onto yet another mnemonic device called the Guidonian hand, on which each knuckle from the thumb to the bottom of the pinky represents a note / solmized syllable from the overlapping hexachords. It’s simultaneously fascinating and terribly byzantine, but Dell’Antonio reminds us to put it into context. “From our perspective, it is very complex. But for whatever reason, this system appealed to enough of the people who are in charge of pedagogy at the time.” Remember, there wasn’t much to go on before this came about.

The move beyond hexachord theory and the addition of the scale’s seventh note happened as music was incorporating more chromaticism and Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) was advancing his theories of music. “Eventually, someone comes along and asks ‘what’s the deal when you go above la?’ People realized that there’s often a half step above la,” explained Dell’Antonio. “So this practice rule emerges that when you sing above la, you should always sing fa.” But that has its limitations, so “someone comes up with the idea with adding one more note above la to get a seven-note system. And that brings us closer to our modern notion of a major scale.” That seventh note was si (Sancte Iohannes). In the 19th century, the English music educator Sarah Glover changed that si to ti, in order for the entire scale to be notated with the first letter of each syllable (sol had already called dibs on the letter “s”). Italians hold onto that si, but English-speaking countries usually sing ti.

Via