R. Murray Schafer, composer, writer and acoustic ecologist, has died at 88

His ‘creative spirit knew no bounds,’ says one former colleague

by Robert Rowat

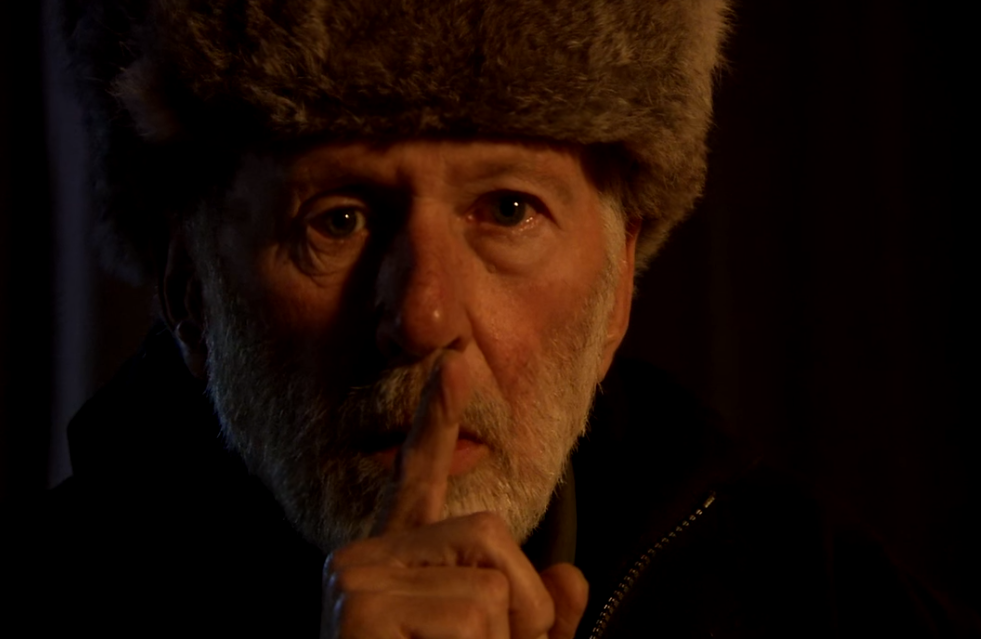

R. Murray Schafer, the eminent Canadian composer, writer and acoustic ecologist who popularized the term “soundscape,” died on Aug. 14 following a struggle with Alzheimer’s disease. He was 88. The news was confirmed in an email to friends and colleagues from Schafer’s wife, Eleanor James.

“The loss of Schafer represents the loss of our greatest composer, one whose creative spirit knew no bounds,” reflects David Jaeger, a former producer at CBC Music and a longtime friend and colleague of Schafer.

Schafer composed a large body of music in all genres — symphonic, chamber, opera, choral and oratorio — and was best known for his groundbreaking creations that were performed outdoors and incorporated sounds from nature into his music.

We are the composers of this huge, miraculous composition that’s going on around us, and we can improve it or we can destroy it.- R. Murray Schafer

His earliest such piece was Music for Wilderness Lake, written for 12 trombonists spaced around a body of water. “I had been canoeing around one of the many unpeopled lakes in the Madawaska area and had noticed how the sounds changed throughout the day and evening,” recalled Schafer in his memoir, My Life on Earth & Elsewhere. “I decided to write a work for the lake and take advantage of those changes.”

There was also the opera The Princess of the Stars. To perform it, musicians gather on the edge of a lake one hour before dawn, with the awakening of birds and the sunrise contributing key elements to the drama. Other characters enter via canoe, chanting lines in a language created by Schafer. A 1985 production of the opera at Banff National Park attracted an audience of 5,000.

‘An ecologically balanced soundscape’

Schafer’s interest in the sounds of nature went hand in hand with his concern about the damaging effects of noise on people, particularly those living in the “sonic sewers” of urban landscapes. In 1969, he founded the World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University “to find solutions for an ecologically balanced soundscape where the relationship between the human community and its sonic environment is in harmony.” He presented his theories and research on the soundscape in The Tuning of the World, published in 1977.

“In a way, the world is a huge musical composition that’s going on all the time, without a beginning and, presumably, without an ending,” he explained in an NFB portrait, produced in 2009 when Schafer received a Governor General’s Performing Arts Award. “We are the composers of this huge, miraculous composition that’s going on around us, and we can improve it or we can destroy it. We can add more noises or we can add more beautiful sounds.”

In 1978, Schafer was awarded the inaugural Jules Léger Prize for New Chamber Music for his String Quartet No. 2 (Waves), acclaim that would prove prophetic: “His 13 string quartets, alone, which span his creative life, are an unprecedented achievement in the Canadian musical canon,” notes Jaeger.

The Orford String Quartet’s recording of Schafer’s first five string quartets won the Juno Award in 1991 for best classical album, solo or chamber ensemble. The same year, Schafer won the Juno for best classical composition for his String Quartet No. 5 (Rosalind).

In more recent years, Montreal’s Molinari Quartet has championed Schafer’s string quartets, giving the premiere of four of them, and recording the first 12. “As performers, we are filled with emotion when playing the Schafer quartets,” writes violinist Olga Ranzenhofer in the liner notes. “Sensitive and refined writing; pure, beautiful sonorities; powerful harmonies; pungently expressive dissonances; impetuous, energetic rhythms; fascinating transitions between episodes — these are just some of the elements that characterize Murray Schafer’s quartets.”

Schafer was born in Sarnia, Ont., on July 18, 1933, and often spent childhood summers with his mother’s relatives in rural Manitoba. He showed talent at a very young age for drawing — remarkable, considering he had been born almost blind in one eye. (That eye would be surgically removed when Schafer was eight, leaving him with an artificial one for the rest of his life.)

Schafer started to learn piano at the age of six and later recalled in his memoir that he “usually played with the windows open [and] would attempt to impress the whole block by means of energetic arpeggios and glissandi across all limits of the audio spectrum.”

As a child, he also joined a boys’ choir, instilling in himself a lifelong fascination with the expressive possibilities of the human voice. Some of his compositions, such as Snowforms, with its vividly pictorial score, have become staples of choral literature.

Despite this early interest in music, Schafer was committed to pursuing a career as a painter. He applied to study at the Ontario College of Art & Design, but because his eyesight was compromised, he was discouraged from enrolling. Instead, in 1952, he began his studies at the faculty of music at the University of Toronto and the Royal Conservatory of Music, where his teachers included Alberto Guerrero (piano), Greta Kraus (harpsichord), John Weinzweig (composition) and Arnold Walter (musicology).

By 1955, however, Schafer got himself kicked out of university and, disillusioned by formal education, opted to go overseas to study music informally in Vienna and England.

He returned to Canada in 1961 and directed the first Ten Centuries Concerts in Toronto before commencing a 12-year period of teaching: first, as an artist-in-residence at Memorial University (1963-65) and then at Simon Fraser University (1965-75). In 1975, Schafer retired from university teaching and began devoting himself solely to writing and composing.

‘A trickster with a hilarious sense of humour’

Alex Pauk, music director of Toronto’s Esprit Orchestra who has conducted 77 performances of Schafer’s music, recalls his friend’s mischievous side with an anecdote:

[Schafer’s] No Longer Than Ten Minutes was commissioned by the Toronto Symphony with contractual stipulations for the piece’s duration possibly aimed at fulfilling content quotas for government support without too much impact on the audience’s tolerance for new music. Such new works were destined to be performed at the beginning of a concert so as not to unsettle audiences with a mid-concert placement. Audaciously, Murray’s score specified that at the end of the piece, with its tam-tam fade-outs, each time the audience began applauding, the percussionists should begin a new rolling tam-tam crescendo and fade out. Each fade out therefore led to a new wave of sound if the audience began applauding. Thus ensued a loop that could go on for much longer than 10 minutes. Was this a naughty thing that Murray did or was his idea to make people aware of time, contemplate the piece they’d just experienced and/or consider the relationship between composers, orchestras and audiences? Certainly we can chalk it up to Murray being a trickster with a hilarious sense of humour but with a deeper intent aiming to advance thinking about music in the best sense. The work is actually a fine piece of music – not a gimmick. But the audience at the premiere sure was confused!

From left, conductor Marius Constant, soprano Phyllis Mailing, composer R. Murray Schafer and CBC producer Irving Glick examine the score of Schafer’s Lustro on the occasion of its premiere by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in May 1973. (CBC Still Photo Collection)

Apocalypsis, a monumental music drama

It was after his retirement from teaching that Schafer wrote one of his most prominent and ambitious compositions. Apocalypsis is an orchestral, choral and theatrical piece based on the Book of Revelation, requiring at least 500 performers. Due to its complexity and scale, it has only been performed twice: first, in 1980 to commemorate London, Ontario’s 125th anniversary, and then 35 years later, in 2015, at Toronto’s Luminato Festival. More than 1,000 artists participated in the latter performance, a monumental music drama that was live streamed by the CBC and later released by Analekta Records.

In 1987, Schafer moved to a farmhouse in the countryside outside Peterborough, Ont. There, he became artistic director of the Peterborough Festival of the Arts and, building upon the esthetics of his musico-theatrical cycle, Patria, he conceived his Wolf Project, a “participants-only collaborative, experiential week of chant, music, theatre and camping” that has taken place annually in the heart of Haliburton Forest and Wild Life Reserve.

Despite an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Schafer continued composing. At 82, he wrote a string quartet titled Alzheimer’s Masterpiece, characterized by violinist Ranzenhofer as “a very moving piece, at times funny, at times passionate, and of course lyrical.“

Wild Bird

“[Harpist] Lori Gemmell and I visited Murray at his farm north of Peterborough on Aug. 3,” recalls Tom Allen, host of About Time on CBC Music. “[Schafer’s wife] Eleanor told us he had not been on his feet in three weeks. He was extremely fragile-looking, and did not appear to respond directly to us at all, but we had with us a very recent recording of his 1997 piece for harp and violin, Wild Bird, played by Lori and violinist Etsuko Kimura, and we played it for him at his bedside. As soon as the music began, Murray, although still lying down and very much in his own world, became extremely animated. His hands danced and he sang rhythmically with tremendous excitement, sometimes with the recording and other times anticipating the section that was coming next. It was profoundly moving. This man, his body and mind ravaged by age, disease and dementia, was still a living, vibrant soul, with music still brimming from his brilliant mind with the same energy it always had.”

As Esprit Orchestra’s Pauk recalls, “Murray generated a unique piece every time he composed. He was perhaps Canada’s most compelling composer with a sure, clear message in every work. That he achieved this while staying on top of sonic environmental issues, pioneering educational methods of ‘ear cleaning,’ creating graphically exciting scores and producing a significant body of books and essays, is a testament to his brilliance, integrity and stamina in the face of the continual challenges of bringing new music to the fore.

“Through it all he maintained a keen philosophical approach, sense of humour and demanding attitude about getting things done as he wanted. Admittedly he was sometimes (reasonably) difficult to deal with (at the edge of scandalous) but, as he moved into the last stages of his affliction with Alzheimer’s, he became ever more gentle with a delicate pleasance about him that could only have been arrived at after achieving a life of artistic glory.”

In addition to his Governor General’s Performing Arts Award, Schafer was made a companion of the Order of Canada in 2013 and in 2005 he received the Canada Council’s Walter Carsen Prize.

When Schafer was awarded the inaugural Glenn Gould Prize in 1987, jury member Yehudi Menuhin praised his “strong, benevolent, and highly original imagination and intellect, a dynamic power whose manifold personal expressions and aspirations are in total accord with the urgent needs and dreams of humanity today.”

Schafer is survived by his wife, mezzo-soprano Eleanor James.