Music As Universal Language? It Starts With Something Local

By Frank J. Oteri

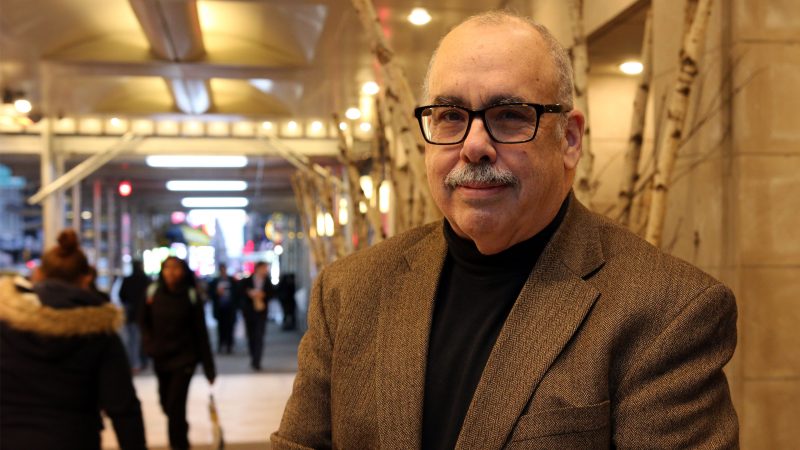

Composer Roberto Sierra frequently likes to tell the story of how, when he was growing up in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, he would hear Pablo Casals playing his cello on television while salsa recordings of the Fania All-Stars blared outside on the street. Most of Sierra’s music—which spans numerous works for soloists, chamber ensembles, and orchestra as well as his massive Missa Latina—has forged a synthesis of these two musical realms. But the question of what kinds of music are local or global is more complex than it might initially seem.

Conceptually, one might argue, Western classical music is tailor-made for global promulgation since a score written in country A in year X could theoretically be rendered equally well by musicians in either country B in year Y or country C in year Z. But, of course, thanks to the advent of recording technology well over a century ago, those folks in A, B, and C can now easily listen to each other. As a result, any locally made music has the possibility of reaching a global audience. In fact, the salsa Roberto Sierra was hearing in Vega Baja was actually recorded in New York City, whereas Pablo Casals moved to Puerto Rico when Sierra was a young child and lived there for the rest of his life.

However, as Sierra pointed out when we met up with him in a hotel room before a performance of his music in New York City later that evening, “the heyday of classical music is Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart, and I think they were still very much localized.” But Sierra went on to explain how the elevation of certain repertoire has made it extremely difficult for the vast majority of composers.

It’s very difficult for any composer, even German composers nowadays, because you have to live with that notion of something that was great and something that is not able to be great anymore. And for the others living in America, or in Latin America, wherever we are, we’re thinking, “Oh my God, we are outside of this canon of great masterpieces of humanity.”

But Sierra—who initially left Puerto Rico to study with György Ligeti in Hamburg in the late 1970s, went on to serve as the composer-in-residence of the Milwaukee Symphony in the 1980s, and has been a member of the composition faculty at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, since 1992—doesn’t bother himself with following a lineage or adhering to a zeitgeist. His piano concerto Variations on a Souvenir sounds like it could have been written in the 19th century while his Second Piano Trio uses a tone row as well as the strict clave rhythm but doesn’t really sound either dodecaphonic or Afro-Cuban.

I always thought and I always commented to other colleagues: You think Boulez is looking over your shoulder, and you’re waiting for his approval or disapproval? In fact, these people do not care what you write. If you’re writing something so that the powers that be will approve of you, composers do not; composers are self-centered! They’re only thinking about their own stuff. So write your own stuff. … I don’t even have Ligeti looking at me.

Roberto Sierra in conversation with Frank J. Oteri at the Park Central Hotel in New York, NY

November 13, 2018—2:30 p.m.

Video presentation by Molly Sheridan

Frank J. Oteri: What’s particularly striking to me about your music is how it navigates the dichotomy of finding ideas, sounds, melodies, or rhythms that are individual to you or that are culturally specific—again, to you—versus things that are, for lack of a better word, global. I’m not going to say universal, because we don’t know what the Martians listen to. You write a piece of music, and you have a very specific cultural background, but then it’s going to be performed by musicians who are maybe in Korea or Slovakia, and who don’t have your cultural experience, yet somehow that music has to translate.

Roberto Sierra: That’s the crux of the matter in terms of my search and yearning for that expression which is local. I have always said that you only go to the universal from the specific, what in Latin is called an internal locus. That internal center is you and then your country of origin, and from that point you go to the universal, if that exists of course, or the global. As you said, in a funny way, we don’t really know what is universal, what the Martians listen to, but also art, literature, and other cultural expressions mean different things for different people in different parts of the world.

For me, it was always important to have that element that represents who I am and where I come from in a very specific manner, Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, and also part of a larger American culture, which is not just one thing. I think it has different ramifications. In a way, it’s like a circle that has a circle around it that has a circle around it, but at the center is what I call the internal locus. So for me, from the very beginning, that sense of identification was important. On the other hand, like many of my colleagues, we are dealing with forms that have traditions that date back centuries. We’re using instruments that have their own traditions that also date back centuries. So it’s a matter of how you combine all of that and make it into a single entity that represents both aspects—that aspect that is global, but at the same those other aspects that are individual. Now how do I do it? How I make the sort of localized into the larger sphere, I think, is a process of refinement and abstraction. Although I have works that are directly connected to the music of the Caribbean, a lot of my music evokes it—it doesn’t really quote it, and I make it my own. So I play within that aspect of the music. I find ways of transforming that rhythm into something that fits my own thinking of how the music should sound. And I do it by technical means of dealing with the object of that rhythm, harmony or melody, modified and turned into my own expression.

FJO: Talking about this feels very timely since in this moment all around the world there’s a struggle between so-called globalists and so-called nationalists. It’s all kind of ridiculous in a way because so many of the things we think of as global—certain musical instruments and certain musical forms—are also culturally specific. The sonata, the concerto, and the symphony all happened in specific places with specific people, as did violins and clarinets, etc.

RS: Those are Central European.

FJO: Exactly. And if you look at it informed by the historical perspective of colonialism and the aftermath of post-colonialism, these things wound up being global because they traveled with their empires and so those instruments wound up in other places.

RS: Inevitably.

FJO: When people talk about Puerto Rico, they think Puerto Rican music is salsa. Right? But salsa happened in New York City where Puerto Ricans were hanging out with Dominicans, Italians, Jews, and African-Americans. And when they played together, they started combining Cuban music with many other elements.

RS: Actually you’re right. It’s here.

FJO: The actual music that came from Puerto Rico is bomba and plena, but there was also a history of so-called classical composers from Puerto Rico such as Juan Morel Campos and Héctor Campos Parsi, who very few people outside Puerto Rico know about.

RS: I always remember, and I have said it before, I used to see Casals playing his cello on the TV at the same time I was listening to the Fania All-Stars playing salsa, music that is actually the urban voice of the Latino community in New York during the ‘70s—as you well said, salsa is basically a New York phenomenon. For me, these two worlds and these two musics co-existed in a natural, organic manner. There was nothing artificial about it. They inhabited the same sound space, so to say, as I was growing up. So inevitably, I think that has to show in my musical expression as well.

I want to address something about the issue of nationalism and globalism. I think nationalism is a bad thing when you “otherize” groups of people and claim that what you do or who you are is better than the others. This concept of a global sort of thinking, which is being disparaged now with this ominous sense that there is something global that wants to control everything—that is to me also a kind of ridiculous premise because, first of all, nobody can control everything. And second, I think we need to be aware that we live on a globe. Although we think locally, there is something larger called the Earth, and we are part of that community, too. So I don’t see the friction between asserting your own voice artistically but, on the other hand, respecting the other voices and not thinking the only voice that needs to be heard is just your voice.

FJO: Something worth pointing out about the co-existence of Casals and the Fania All-Stars for you growing up is that at that time Casals was based in Puerto Rico so he was local, whereas the Fania All-Stars were what was global; those recordings were made in New York City and finding their way into Puerto Rico.

RS: Yeah absolutely, but it was the sound of the streets in Puerto Rico.

FJO: Of course. But the other interesting thing about classical music is that in a way it was designed to be globalist, since the whole idea is that you write something down and then other people are playing it who may be your neighbors, like Casals, but may also be somebody from tens of thousands of miles away from you or, eventually, 200 years away.

RS: But I think in its origins, just like I would call the Fania All-Stars the heyday of salsa, the heyday of classical music is Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart, and I think they were still very much localized. Maybe Bach had aspirations of globalism, but I think he was writing for the church right there, Saint Thomaskirche in Germany.

There is this mythology that has been built into what we call the canon, therefore the sort of accepted universality of that to me is a great conflict actually. It’s very difficult for any composer, even German composers nowadays, because you have to live with that notion of something that was great and something that is not able to be great anymore. And for the others living in America, or in Latin America, wherever we are, we’re thinking, “Oh my God, we are outside of this canon of great masterpieces of humanity.”

FJO: It’s interesting to hear you say that since specifically in your instance, even though you’ve written a great deal of music in many other idioms, you write a lot for orchestra.

RS: A European instrument.

FJO: Exactly. And also a European structure. Of all the different mediums for transmitting music, the orchestra one is one of the hardest ones to budge for a variety of reasons—the amount of rehearsal time, contracts—

RS: It’s always down to money.

FJO: Of course, but because of that, it’s one of the hardest places for new music to really make a dent.

RS: Yes.

FJO: So you get to have one piece on a program. Maybe it’s an opening fanfare or, if you’re really lucky, the concerto.

RS: In the middle.

FJO: But no matter what you do, you’re surrounded by old music that is revered—timeless masterpieces which you can’t compete with.

RS: Adored by the others and we’re already prejudged. We are the outsiders and the other music is the great one.

FJO: And even if some people in the audience don’t actually know the older music that’s on the particular program you’re part of, they’re fed this idea that they should think that music is better than the new piece. They don’t get to make an opinion about the older pieces. They can’t say, “I think Dvorak’s Ninth Symphony is boring.”

RS: Or this piece by Tchaikovsky is weaker than this other one. No, they don’t do that.

FJO: So you enter this and it ties your hands in a way about the kind of music that you can do. You can’t write something that’s so far away from what that music is. No matter how much we might admire his music, most of that audience doesn’t want to hear Anton Webern, since that music sounds totally different and unrelated to everything else on the program. So you have to find a way to write something that can coexist with that older music to some extent and not come across as cognitive dissonance. I’m curious about how that plays out in your own compositions.

RS: I think it does. I think it does in the same way for all my colleagues who write for orchestra actually, because what you said is absolutely right. You’re placed in a context that is loaded with premises, which is what we were talking about. I think you have two options. You can either do something that is disenfranchised from everything, and therefore you’re not going to communicate with that audience and have the possibility of making a dent into that insurmountable wall that is there. Or you can do something that, while being true to yourself, approaches the audience without pandering to them. And that is a very fine balance, I think.

But I will be even more extreme than what you said. For even those people who try to be very popular and try to write absolutely at the center of tonality, thinking that the audiences will like that, in fact because of what you just said, this pre-judgment that is made, no matter if it sounds like Dvorák, the audience will still not think it’s as good as Dvorák. It’s a very unfair situation for composers, but one that we have dealt with and we are dealing with because there are still people writing for orchestra. But there are also a lot of people that have bypassed the orchestra precisely, I think, because of those reasons.

FJO: But you haven’t.

RS: I haven’t, although I write a lot of chamber music and I write a lot of solo music. I haven’t, because I like the orchestra as a sound. I call it an instrument; of course, it’s not. It’s many instruments, but it’s an instrument of sorts. And I enjoy that sound. This is part of that notion of growing up hearing those sounds on the TV at the same time that I was hearing the salsa music in the street. In what I do, as I said earlier, these two things coalesce into a single entity. I don’t know if people really appreciate that. Maybe they do, maybe they don’t. But I don’t care; I just do it.

FJO: Well, to get specific, one of my favorite pieces of yours, which is a very unusual piece in a lot of ways, is a piano concerto you wrote that’s inspired by a piece by Gottschalk, your Variations on a Souvenir.

RS: Oh, yes.

FJO: Of course, Gottschalk had been inspired by some Puerto Rican folk song he heard. First you wrote a solo piano piece derived from the Gottschalk, then you wrote this concerto. But what’s so interesting to me about the concerto is that piece sounds like it could totally exist within the canon of standard repertoire. It totally could have been a 19th-century piece.

RS: Yeah, yeah.

FJO: There’s nothing about it that wears a badge saying, “Listen to me; I’m 20th-century music.” Of course, now we’re in the 21st century. So what does that mean? Right? But for me this piece plays that particular game—the game of temporal illusion—very effectively. Which is interesting, because the solo piano piece sounds more contemporary.

RS: The other one [Reflections on a Souvenir for solo piano] is a reflection on the variations. I wanted to do something modeled on this 19th-century tradition. I’d like to make a parenthesis here to say that I’m very interested also in the pianistic tradition of the 19th century. The piano is my instrument. Part of the idea was to examine that pianism. In fact, right now, I’m writing a series of piano etudes after the Transcendental Etudes by Liszt. It’s a play on the notion of Liszt writing a sonata after a reading of Dante, which is the so-called Dante Sonata. So I’m doing a series of etudes after the original of Liszt, so in a way, it’s a different piece from this concerto you’re referring to. But in a way, it’s a play on 19th-century virtuosity in piano.

FJO: Well, one of the things we alluded to before is that there were important composers in Puerto Rico going back to the 19th century. Gottschalk went to Puerto Rico back then, but Juan Morel Campos was active not so long after that.

RS: Juan Morel Campos was a late 19th-century composer who composed a lot of salon pieces. Also, when Gottschalk came to Puerto Rico, he didn’t come as a solo pianist. He came with a singer called Adelina Patti. He toured not only Puerto Rico, but he went to Cuba and he went to South America touring as a virtuoso pianist and also touring with a singer. Of course, Gottschalk is one of the first important figures in American music. And he had the good sense of not only bringing his own music, but also absorbing the culture in the way that he could. And he understood it. So, going back to [his] piece, Souvenir [de Porto Rico] uses a song called “Si Me Dan Pasteles.” And nowadays it is still sung in Puerto Rico, totally unrelated to Gottschalk, but related to a Christmas carol.

FJO: Wow. So in a way, you took this thing that somebody came to Puerto Rico and took, and you brought it back there.

RS: I took it back!

FJO: But in a totally 19th-century way, which I find fascinating. But that also leads to this interesting question of what contemporary music should sound like. When we were both growing up, there were all these debates. But now that we’re in the 21st century, you could turn around and say, “Even Boulez and Lachenmann is old music at this point.”

RS: It is historical music already. Yeah.

FJO: So now we can do whatever we want. In a way, it’s pretty liberating.

RS: We could always. That is the training that we could always do whatever. I studied with one of the great modernists, Ligeti.

FJO: But he was a very unusual and undogmatic modernist in many ways

RS: That’s perhaps why I could study with him.

FJO: So what impact did Ligeti have on your music?

RS: I was asked this recently. I think one of the great things about Ligeti is that he never forgot humanity in his music. Ligeti was a great communicator. There is always a fantastic sense of drama in his music—be that Atmospheres, which is just clusters of sounds with an orchestra, or the later pieces that are also sort of 19th-century oriented, like the [Horn] Trio. And, of course, he was a great master technically. I think that’s why he was a great composer. He combined both things. And to be an example of “do your own thing,” I can say, “I don’t see why we have to follow any dogma.” It’s your music. You’re writing it at home, you know. Why is it that you cannot do what you want? Because I lived [through] part of that period that is now historical—in the ‘70s, specifically, and ‘80s—I always thought and I always commented to other colleagues: You think Boulez is looking over your shoulder, and you’re waiting for his approval or disapproval? In fact, these people do not care what you write. If you’re writing something so that the powers that be will approve of you, composers do not; composers are self-centered! They’re only thinking about their own stuff. So write your own stuff.

I’m teaching a seminar on the music of Stravinsky. There’s a book I was reading about Stravinsky as a teacher, which he never was. He said something to this effect of he never had the slightest interest in teaching composition. And he said, “When people came to me for advice, I would just say, ‘Well, I would do it this way,’” which is not teaching anything. It’s just telling the person how he, Igor Stravinsky, would do it. Another aspect of these dichotomies and this kind of dogma and imposition that became culturally acceptable is it’s very interesting to see the relationship between Boulez and Stravinsky, which was very bad actually. Boulez saw Stravinsky’s work as very uneven and not that interesting. He’s talking about neo-classicism of course. But even the later serial music when Stravinsky discovered Webern so to say, Boulez never liked it. So there is again this fallacy of understanding that there is one way to write music, which is the current one, always forgetting that that current way will [later] be historical and old fashioned, like you said. This is not to say that the music is bad, it just becomes démodé. Everything becomes démodé. I mean, even Ligeti now is a historical figure.

FJO: But it’s interesting to hear you talk about Ligeti never losing his humanity. What’s so exciting for me about the late Ligeti works is he got very interested in syncopation and rhythm, which has been so central in your music. In some of the earlier works of yours that I’ve known since the ‘90s, like the Piezas Caracteristicas or the Tres fantasias, the Caribbean rhythms are there, but they’ve sort of been fractalized in a way that actually, at least to my ears, has some connection to late Ligeti.

RS: Oh, absolutely. I was in Hamburg in that period. There is a book on African polyphony that Ligeti wrote the preface to. It’s a very important book on African polyphony. And Ligeti wrote in the preface that it was me who introduced him to these African rhythms in 1982, and also to Caribbean rhythms. So I was still a student. I wasn’t [yet] writing these pieces. But there was an interaction and he was very eager to learn about that. I remember that—and this is also documented by Ligeti—I gave him some recordings of the Banda Linda for example, music of West Africa. And that did have an impact on him. Not that he wouldn’t have done something rhythmically that way, but that orientation came at that point.

FJO: Then also his discovering Conlon Nancarrow.

RS: Well, that is his own discovery. I discovered Nancarrow through him. I actually met Nancarrow through him. I met him once with Ligeti, and then I also visited Nancarrow in Mexico towards the end of his life. He was a very important composer, also another composer who did whatever he thought he needed to do, totally outside of this sphere of influences or fashions. But I think Nancarrow’s music has a great debt to Stravinsky.

FJO: And to jazz.

RS: Of course. Nobody’s devoid of influences.

FJO: But we like to perpetuate the illusion that great composers are. Beyond the discussions of cultural specificity and global impact, there’s always talk of individuality and great composers finding their distinct, individual voices. Once again, I think in the 21st century, that kind of falls apart. This idea of individuality was very tied to the German Romantic ideal that deified Beethoven and then Wagner. It’s a terribly egotistical and possibly dangerous cultural model.

RS: Like that bit of advice by Lord Byron, in which a heroic figure can be evil actually and he’s accepted as long as he’s individualized.

FJO: We see how this is now playing out once again in the political sphere with leaders around the world, the whole cult of personality.

RS: Exactly. As long as we’re breathing and talking to each other, we are influencing each other. It’s as simple as that. So to say “my writing” or “my music” or “my painting,” whatever that may be, “doesn’t look like anybody else’s; it’s so unique”—well, maybe in their own minds. As long as you sit down at a piano, there is a whole tradition of piano playing no matter what you try to do, unless you burn the piano, and that has also been done already actually. These are fantasies that we build and then they make them reality by means of proselytizing about it. But they’re basic fallacies.

FJO: In a way, they’re very harmful fallacies. This idea that you have to be original and then there are certain great people, and they’re inevitably men—white men. These are the great people. This is their great music. These great individuals did that and everyone else is just second rate.

RS: Going back historically, Mozart was not really that original in many ways because he was doing what other people were doing around him. He just did it beautifully. And he just did it maybe better than other people. But pushing the envelope in that way is a very modern construction. I don’t think it was in the heads of many of the people in the past. It’s also manipulative, because if you claim to be the original one, that gives you a lot of power and makes the other ones followers. It becomes like a political party.

FJO: Exactly. And we see how it played out in music history. Even the 12-tone system of Schoenberg was something that was being developed contemporaneously by another composer completely independent from him, Josef Matthias Hauer.

RS: And Krenek.

FJO: Yeah. So all these things evolved. There are certain things that are in the air. But to take this back to reconciling the individual with the people who are around you and getting back to what we were saying about how to effectively write music for the orchestra.

RS: It’s a public apparatus.

FJO: So in a way, you can’t be completely original. And, as you pointed out, you also can’t be completely original with the piano because that instrument was built to do certain things.

RS: I would say that, at the end, do something beautiful. Do something gorgeous. Do something that comes from your heart; that may be the original part. You know, that’s the example of Mozart. Of course, there are composers who have done things that are maybe unprecedented in some aspect. For example, talking about pianists, some of Chopin, but then there is Carl Maria von Weber before Chopin, and John Field writing nocturnes that sound like Chopin, but he was writing them before Chopin. Chopin is indebted to John Field. It’s just that Chopin did it to the Nth degree of exquisiteness. Hummel was another predecessor. These are names that are historical, now nobody knows about it. But the way we isolate Chopin is also not completely correct.

FJO: There are significant composers who have been even further marginalized than Weber or Field. There was also Maria Szymanowska, a woman composer who was writing a similar kind of very idiomatic piano music before Chopin and her music might have influenced him; it’s music that he quite possibly heard. But she’s largely erased from history.

RS: Exactly and then we are talking about gender bias, which is tragic also.

FJO: Which still is happening.

RS: Of course.

FJO: Particularly in the classical music sphere…

RS: We’re living it.

Roberto Sierra’s Triple Concierto with Trío Arbós and the RTVE Orchestra conducted by Carlos Kalmar

Cecilia Bercovich, violin

José Miguel Gómez, cello

Juan Carlos Gravado, piano

FJO: But if you write for the orchestra you’re stuck co-existing with the canon. So the trick is to find ways to create work that can co-exist with it. Concertos are a good example since they are such an important part of concert programs and you’ve written so many concertos. Of course, one way to introduce a new twist is by having a percussion soloist.

RS: Yeah.

FJO: You’ve written three percussion concertos. You can do certain things within that format that you can’t really do if, say, you were just writing for a percussion section within the orchestra. It can become the focus.

RS: Yeah, because also percussion is entrenched within my own cultural sphere, that internal sphere of Afro-Caribbean currents and culture. And also, if you get a good soloist, that’s a great vehicle for the piece having a life, so to say.

FJO: You’ve also written quite a lot of music for guitar, specifically acoustic guitars as opposed to electric guitars.

RS: I haven’t written that many, it’s just that they’re performed very often. Let me count them. I have a guitar sonata, a guitar duo, I have three concertos for guitar…

FJO: Plus the one for two guitars, so that makes four concertos. Then you also have a fifth concerto that’s for guitar and small ensemble.

RS: Pequeño Concierto. Yes. So it’s like 10-12 pieces.

FJO: That’s quite a bit, I think.

RS: Yeah, but not so much for solo guitar. I came to write for solo guitar recently and this Guitar Sonata has become sort of an item of the repertoire now. That is also something that is very nice when you see it happening—something that we cannot control because it’s up to the players, whatever they want to do. It’s an instrument that I don’t play, but it’s also tied to that inner circle of culture—it’s an instrument that can be identified with Latin American culture at large.

FJO: Well that’s the interesting thing, for the Hispano diaspora culture, the guitar serves as a sonic identifier. And in the orchestra community, for better or worse—I think mostly for better, since it’s a great piece—when people think of the guitar they think of Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez.

RS: It’s a masterpiece.

FJO: It is an amazing piece, but of course, every time composers write guitar concertos, they’re competing with that.

RS: Yes, that is like the equivalent of all the other symphonies of everybody else; it’s just that piece. You’re right.

FJO: In the dream list of pieces I wish you would write, I’d love for you to focus on an instrument that’s specifically Puerto Rican and compose a cuatro concerto.

RS: I would love to. People have heard a cuatro a lot recently in “Despacito,” of course. The introduction has a cuatro and that famous song has traveled the world. It’s a great instrument. It’s a matter of finding the right elements—the orchestra that would like to do it and the player that would like to play it. And, like many folk instruments, a lot of players within that sphere don’t travel outside that sphere, but there are younger players now that I think would do it. There’s a younger generation of players that extrapolate and not within just one type of music.

FJO: So it is a piece you would want to write?

RS: Of course.

FJO: So now we have to find someone to commission it! Let’s talk about chamber music for a bit. A form that you’ve returned to many times is the piano trio. You’ve done at least four of them that I know of.

RS: Yeah.

FJO: Once again, that’s a very standard classical music combination.

RS: As traditional as it gets.

FJO: But you’ve done very untraditional things within that.

RS: Yeah.

FJO: So it’s like you seek out these traditional boxes, and then find ways to open the boxes, and put other things in them. Your first piano trio does all this stuff with Caribbean rhythms, but I want to talk a bit about the second one, because the second one is a really peculiar piece, because in it you use a 12-tone row although you don’t use it serially.

RS: Seriously or Serially?

FJO: Serially.

RS: Yes, I did it very much on purpose. I always place a challenge—well, not always, but in many cases, I place a challenge to myself. I try to avoid repeating the last piece. I think that’s typical of all composers. I don’t know why, because in the past composers kept repeating their last pieces. Some of them all in a row, great pieces. Maybe it’s another 20th-century habit, let’s call it. So in this case, I wanted to do something different. So I said, “What if I use a 12-tone row?” And so I did. I took a row, but handled it in a nontraditional manner, that is a non-Schoenbergian manner, and infused it also with clave rhythms. If I remember correctly, the first movement has a clave rhythm going through it and the 12-tone row going through it at the same time. It was, in a way, an experiment, but in the end, I was very happy with the result. I think in my mind the experiment worked.

Roberto Sierra: Piano Trio No. 2

Performed by Continuum

From the album Turner: Chamber Music of Roberto Sierra

Licensed to YouTube by The Orchard Music (on behalf of New Albion Records)

FJO: It’s a very cool piece, but it also leads to the question of interpreters. What you said about the clave going through it. There are certain things that you can do with notation; it’s a very, very powerful tool. It allows us to play music that was written halfway around the world from 200 years ago, and if you’re good, do a convincing job of it. But one of the things about Caribbean Latin music that is so endemic to it is this idea of tumbao. It’s a feeling that’s difficult to translate to someone not acculturated to it, this concept of walking with tumbao.

RS: Yeah, it’s a little bit skewed. It’s not a military march.

FJO: And, in a way, you either you have it or you don’t. You can try to write it out precisely on paper, but if you get a player who’s going to be totally mechanical, it just won’t sound right.

RS: That’s right. It’s going to be put straight.

FJO: So how do you deal with that in terms of working with musicians, especially with orchestras where you probably have very little time to work with the players? Maybe you get to work with the conductor. In chamber music, I feel like you might have more room to get across how the feeling should infuse the music.

RS: When I wrote the early trios, for example, it was more difficult. But there is something peculiar happening now. There are so many younger players that know salsa, have heard salsa, played salsa, love salsa, dance salsa. Not only salsa. Jazz. They know music from other cultures, so I think it’s less of a problem now, but indeed I have witnessed how problematic it can be. And, as you say, notation is a fabulous thing, but the fact is notation only goes so far. And of course, the great traditions of Europe, they have been handed down, passed through oral traditions. So at Juilliard you get violin students, and from the start the teachers would be telling them without telling them how to phrase. They would say, “No, no, do it this way.” So they’re fed that. That’s not the case with the tumbao. Now that I mention tumbao, or “in tumbao” as we say, in May, at a young people’s concert, the New York Philharmonic will play the tumbao movement from my third symphony. So we’ll see how they do with that. But I bet it will be good, because again this is New York. All of the players would have heard that music at some point in their life. So it is not impossible, but it’s still something that you have to negotiate.

FJO: It’s interesting to hear you describe your third “symphony,” which is “La Salsa.”

RS: That’s right.

FJO: But you actually use the Spanish word—sinfonía.

Roberto Sierra: Sinfonía No. 5 “Río Grande de Loíza”

I. Endecha

II. Súplica (text by Virginia Sierra)

III. Visiones

IV. Río Grande de Loíza (text by Julia de Burgos)

RS: A lot of my titles are in Spanish. It’s just hanging on to the language a little bit. But then a lot of the instructions within the score are in English. English is the lingua franca of today. You travel the world and you were just in Cyprus; you were probably speaking English most of the time.

FJO: Well, it’s a former British colony. And it was the one language that enabled the Greeks and the Turks there to communicate with each other.

RS: Yeah, the lingua franca. Yeah.

FJO: But I wonder if by not actually using the word symphony, if you were also trying to find a way around how loaded the English word for that form is.

RS: Yeah. It’s interesting that you asked because I’m thinking about it, and I’m thinking, “Why did I do that? I could have it called it symphony; it would be fine.” But I didn’t. I think it’s both to signal that this is not a traditional symphony, because they are not really traditional symphonies in some ways or in many ways. And also that I’m going to do my own symphony. I’m not going to try to do either the symphony based on a European model, be that a Mahlerian concept or later Shostakovich—or Stravinsky symphonies, which are his own symphonies by the way. Stravinsky adapted the symphony to his own idiom. And in a way, maybe that signals to that.

FJO: Well, I think of Bartók, who refused to write a symphony because he was living at a time when the Nazis had taken over Germany and for him the symphony had this very German connotation and something of a capitulation to the culture of an occupying power.

RS: Absolutely. And in connection to that, one of the things that I have always kind of mused about is that a lot of the European art or the vanguard art that came after Bartók was a rejection of the European past. I always was mesmerized with why we did that in this hemisphere, too—not having the same situation, because we didn’t get to that point of being invaded or the pressure from the Germans. We fought the war over there and won of course, but we didn’t have the same cultural situation as somebody like a Jewish person living in Berlin, being a German Jew. We didn’t have that, yet we tried to write music like that in the ‘60s. You know, trying to write music that would forget the immediate past, meaning tonality or forms of that kind. To me that was always an artificial extrapolation in this hemisphere.

FJO: And particularly, I think in the case of so many composers, and specifically you, that it’s not about forgetting. The break with the past that was encouraged by the avant-garde after World War II was all about erasing the past. Zero hour. But your music is about having us remember. Whether it’s having us acknowledge Gottschalk’s visit to Puerto Rico or having us celebrate, in the cantata [Bayoán] you wrote based on his words, Eugenio María de Hostos, who was this very important Puerto Rican poet-philosopher-novelist, but to a lot of people that’s just the name of some college in the Bronx.

RS: That’s right. He was an important figure, seminal actually for the whole Caribbean. And my last symphony, which I wrote two years ago, is called Rio Grande de Loiza. It uses a text by Julia de Burgos; it’s the first time I did something with her poetry actually. Julia de Burgos died in abject poverty here in this city. An amazing poet, so again it’s that resonance that you’re talking about—whatever I can do within my own sphere, bringing those elements together and remembering them.

FJO: Obviously Puerto Rico has a very unusual relationship with the United States. It’s controlled by the United States, but it’s its own thing; it’s not a state but it’s also not its own country.

RS: It’s called a commonwealth, which is a very vague term. Is it common? Is it wealthy? I don’t know.

FJO: I was there a few years ago to attend a conference organized under the auspices of the International Music Council and to give a talk to the composition class at the conservatory in San Juan. It was so peculiar because while it really felt like I was in another country, I didn’t need to go through passport control.

RS: You’re still in the United States, but—

FJO: —And most people speak a different language.

RS: Yeah.

FJO: I’m curious about how the international community describes you when your music is done in Europe or in Asia. Are you identified as an American composer or a Puerto Rican composer?

RS: You mean myself or the way they see me?

FJO: The way they see you and how they talk to you about it.

RS: I was born in Puerto Rico. So I’m from Puerto Rico the same way perhaps that some people may say they’re from Alabama, in the sense that we are part of the United States, but Puerto Rico has its own idiosyncrasies. It has, as you said, a different relationship to the mainland than any other state. We’re not a state. We’re called a commonwealth. So I identify myself as Puerto Rican, but now I have been living in the United States and there’s going to be—I don’t know when, but soon—a point that I would have lived more here in the [continental] United States than in Puerto Rico. So I consider myself from Puerto Rico, and I also consider myself working here as part of the larger concert of American composers. And I was born an American citizen, so legally that’s what I am. But there is that sort of ambivalence always there, I think.

FJO: I came across a program when your music was done at the ISCM World New Music Days in Mexico.

RS: When was that?

FJO: Decades ago.

RS: Yeah.

FJO: They identified all the composers by country.

RS: I prefer it wasn’t even there.

FJO: But you’re identified as being from Puerto Rico.

RS: No mention of USA?

FJO: No USA.

RS: It should have been Puerto Rico slash USA.

FJO: But it didn’t say that. It just said Puerto Rico.

RS: In Europe, I think they would do the same, but it’s up to them. I don’t decide that. They know that Puerto Rico is part of the USA. So maybe it’s more of a statement from their part when they do that. I don’t mind either way. It’s inevitable. But I am an American citizen. I was born an American citizen in an American territory. You could have been born in Puerto Rico, too, for that matter, if your parents would have been there. There are many Americans that have been born there, stationed through the Army bases. There are many Americans that married Puerto Ricans who are living there, so it’s a very kind of fluid situation. The funny thing is that the United States is morphing. Those distinctions are less obvious than they were before. And that has to do with demographics as well. Especially you can see it in the cities. New York has been characterized as much by its own New York-ness as its own sort of Latin aspects that were always present—something that Leonard Bernstein never forgot and never ceased to acknowledge in his own music.

FJO: And there’s been a huge diaspora of Puerto Ricans, to the point that there are now more Puerto Ricans living in the mainland United States than in Puerto Rico.

RS: Yes, absolutely. And they are concentrated not so much in New York. It’s interesting how the diaspora has moved away from New York City. I think there are now more in Florida, and even in other states north of here. I mean, they’re everywhere.

FJO: When we first met, you were in Milwaukee.

RS: That’s right.

FJO: You were the symphony’s composer in residence.

RS: A very unlikely place.

FJO: But they’ve continued to commission you for many years after that.

RS: The third symphony was commissioned by them.

FJO: You’ve had this ongoing connection to Milwaukee. They even recorded your mass not too long ago. I haven’t spent a lot of time in Milwaukee, but I imagine that being a Puerto Rican composer, incorporating Puerto Rican musical elements into your music, is more exotic in Milwaukee than it would be in New York.

RS: Probably so. Yes, I think you’re right. I mean, we’re talking about the real Midwest, a place that has their own cultural milieu. It’s basically Central European—Polish, German, those regions of Europe. You can still see the ethnicity. They very much look like that. I had a very good time with the orchestra. I think they enjoyed my presence there, specifically at that time—we’re talking the year 1989. I think that it was important in a way, culturally, for them to be aware of people that are not exactly the way they look or people that were not raised in this country, writing sort of art music, so to say. And I think that probably had an impact in the cultural scene of the city. I don’t know how much of an impact, but it definitely meant something.

FJO: Definitely, I say this all the time, through hearing someone else’s music we can experience a different kind of cultural milieu and that’s the way we can learn to understand each other better.

RS: Yes.

FJO: We’re suddenly not that different from each other if we can listen to each other.

RS: Well, going back to Bach and his Italian Concerto—that says it. Bach became a better Bach by assimilating the music of the Italians and the French. I think being isolated is not a healthy state of being.

FJO: Now in terms of pieces with a global message, we should talk a little more about your mass, the Missa Latina, which to date is your magnum opus. It’s even longer than your opera.

Roberto Sierra: Missa Latina

performed by Heidi Grant Murphy and Nathaniel Webster with the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Andreas Delfs during the Casals Festival

RS: It’s longer than many other masses.

FJO: Well, most of them. It’s up there with Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. It’s a big piece, but it’s been done a lot.

RS: Yes.

FJO: And it’s sort of an outlier in your output. I know that you wrote a Lux Aeterna, which I’ve never heard, but other than that you haven’t really written sacred music.

RS: You’re absolutely right. I do want to write a requiem, but maybe later. Not immediately. That’s a piece that is very dear to me. I don’t say this in a narcissistic way, but I like the piece and I think even though it’s very tonal, it’s also original in many ways. It has originality that is below the surface. And it’s also music that has a great power of communicating. I’ve witnessed performances, not all of them, but in the ones I’ve witnessed, it opens up to the people that listen to it. And, by the way, talking about length, there is nothing else on the program. And people stay with it. It has been done already like five or six times by different orchestras; that’s impressive because of the length of the piece and the commitment of that. But I think there’s something that I did there that has some kind of power, to be able to do that. Again, that part I cannot control, it just happened. I remember writing it, writing it with everything I had in me. I don’t know that I could replicate that piece again. That is a piece of that moment.

FJO: Early on, you’d written an opera, which I haven’t heard—

RS: —El mensajero de plata.

FJO: Is opera something you’re interested in going back to at some point?

RS: I am interested, but opera is a peculiar world, because of the economics of it. I would like to write an opera where I would have the freedom of doing what I think I need to do. I just wrote a dramatic piece; it’s not an opera, it’s just scenes based on Carmen Miranda. The singer Abby Fischer did it in Pittsburgh, and she’s going to be doing it in Ithaca in April. I was testing the waters of using music as a vehicle for a dramatic situation in that piece. So it’s in the back of my mind, but it has to be the right circumstance for me to engage with it.

FJO: Since you mentioned Ithaca, we’ve kind of been talking around it, but you’ve been there a very long time. That’s now your home.

RS: Since ’92. Well, actually I live now in Camillus, which is an hour away from Ithaca. We moved to be nearer to the grandkids, but it’s same area.

FJO: So what made that be the place that you made your home?

RS: I got the job at Cornell, and Cornell is a fantastic place to be. It’s a great university. The intellectual stimulus there is fantastic. I felt very welcome there, and I’ve had a great time. I also grew up intellectually there because the libraries are fantastic and the access to information, dealing with musicologists or theorists—somebody like Neal Zaslaw, one of the preeminent Mozart scholars. To be at one of the places where performance practice started in this country—I was there with Malcolm Bilson, Neal Zaslaw, James Webster, so it was a fantastic place. Still is. So that has kept me there. Ithacans like to say we’re centrally isolated, but it’s not isolated.

FJO: And in the composer community there, there’s no one looking over your shoulder telling you what to write?

RS: Well, I always ignore that, but a lot of my colleagues had Boulez here and Stockhausen here. I don’t even have Ligeti looking at me.

Video Presentations and Photography by Molly Sheridan

Transcription by Julia Lu