March to your own drummer: The history of hennaed drums

Part One

I have a friend who is a musicologist specializing in Sephardic music, and for months we have been trying to arrange for me to henna some of the drums in her extensive collection. So far we have failed to successfully co-ordinate it… So in lieu of hennaed drums, I offer her this blogpost series about hennaed drums; hopefully we’ll be able to make it happen in reality soon!

This is the first of a three-part series, combining history and a how-to — the first part focuses on hennaed drums in medieval Spain, the second on hennaed drums in 19th and 20th century North Africa, and the third on modern hennaed drums, with some helpful tips from contemporary henna artists!

Hennaed Drums in Medieval Spain

The ultimate origin of hennaed drums is probably impossible to find definitively. Wherever people were using henna on skin, and had drums, it would be a logical extension to decorate your drumheads with henna. Drumheads will stain beautifully — they are skin, after all — and the colour will be deep and permanent (since the animal’s skin is no obviously longer growing).

Some of the earliest records, to my knowledge, that may allude to hennaed drums are from al-Andalus, the medieval kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula (today Spain and Portugal). While I have not been able to find any textual references to hennaed or decorated drums, a number of examples of medieval art, both Jewish and Christian, depict drums that have designs on the membrane.

The decorated drums of the Golden Haggada, Barcelona, ca. 1320

The subject of the paintings is often the prophet Miriam dancing and singing with the women after the crossing of the Reed Sea. As is common in medieval art, although the events depicted took place in another time the characters are depicted as if they were living in the contemporary period — the clothes, instruments, and other objects were shown as recognizable to the viewers, as a way of drawing a direct link between the events of the Exodus (for example) and the celebrants at a Passover seder in 14th century Catalonia. “In every generation,” we read in the haggada [Passover servicebook], “one must see themselves as if they had themselves left Egypt.”

The drums shown are handheld frame drums, known as adufes or panderos in Spanish (tympana in Latin, tof in Hebrew, and duff in Arabic). They have a long history in the Iberian peninsula, and are deeply linked with religious ritual and symbolism in local Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities. It is especially associated with women, and in artistic iconography the frame drum is associated with Miriam in particular.

To learn more on the symbolism of the frame drum in medieval Iberia, check out the extensive work of Mauricio Molina (e.g. 2007 and 2010). The frame drum’s importance continues for contemporary women in Spain and Portugal, as well as in the Middle East, as shown by Judith Cohen (2008) and Veronica Doubleday (1999). As Cohen writes, “perhaps [for contemporary Spanish and Portuguese women] playing the adufe and singing is an affirmation — for themselves, for each other, and maybe for the community as a whole — of their strength: physical, emotional and aesthetic.”

But returning to the Middle Ages, the key question for us is: are the decorated drums that are shown in medieval art hennaed? It’s hard to say definitively. After all, drums can be decorated with a variety of paints and dyes, and painted drums are documented in places around the world where henna was unknown — Norway, Chile, Australia… On the other hand, in places where henna is known of, it is a strong contender, since it is one of the best ways to adorn a drum without affecting the sound tone or having the paint rub off on your fingers (and, as we’ll see in our next post, we know of drums being hennaed in North Africa in the last few centuries).

In al-Andalus — an area where we know henna was being grown and used extensively — it’s reasonable to assume that henna was used to decorate drums, especially if the colour matches.

This famous image, for example, from the magnificent (and mysterious — see Epstein 2011: 129-200) “Golden Haggada” (BL Add. 27210), produced in Barcelona around 1320, shows two women with decorated drums — a square drum with a eight-pointed star design covering the front, and a round tambourine (note the carefully drawn cymbals) with a simple round border.

Golden Haggada, Barcelona, ca. 1320, folio 15a.

The designs of both drums are painted in a brown colour and it seems reasonable to suggest that these represent hennaed designs. The designs are clear and, while simple (remember that the drums in this image are less than a square inch in size), would be beautiful inspirations for contemporary hennaed drums.

The eight-pointed star is commonly found in both Islamic and Jewish medieval art — while modern readers might be more familiar with seeing the six-pointed star in Jewish art, the so-called ‘Star of David’ was not adopted as an exclusively Jewish symbol until more recently, in the 17th century or possibly even later. Both hexagrams and octagrams were widely used as geometric elements in mosaics, architecture, wood carving, painting, and other media. These stars, known as ‘the seal of the prophets’ and ‘the seal of Solomon,’ are foundational symbols for the symmetry that underlies the complex geometry of Islamic and Jewish art, and which philosophically represents the unity that underlies all being.

Another decorated drum is shown in the “Hispano-Moresque Haggada” (BL Or. 2737), produced in Castile in the late 13th or early 14th century; like the Golden Haggada, the illustration shows Miriam dancing with Israelite women. Miriam holds a round drum with a decorated border, shown in light and dark brown, with a red fleur-de-lis (outlined in brown) in the centre. This also seems likely to be henna, and the use of different colours suggests that this design was shaded or two-toned in some way; another wonderful inspiration for a contemporary drum.

Hispano-Moresque Haggada, Castile, 14th century, folio 86v.

The fleur-de-lis is a prominent symbol in medieval art and heraldry — in Christianity, often associated with the Virgin Mary. What it’s doing on this drum is anyone’s guess. Is this implying an equation between Miriam and Mary? In the hands of a Jewish artist, this might be an attempt to claim the superiority of ‘our’ prophetic female figure, just as pure and holy as Mary but representative of a living and vibrant (red) tradition rather than the dead and sterile (white) line of Jesus (lest you think I’m totally off-track, similarly provocative and transformative themes around Mary have been noted in Jewish art before — see Epstein 2015: 151-152for an example). Or is there any connection to Florence, the flag of which has been a red fleur-de-lis since 1266? Just throwing some ideas out there.

Fleurs-de-lis also appear on another decorated drum in the hands of an Israelite woman, in the illustration of the “Kaufmann Haggada,” produced sometime in 14th century Catalonia. Here the drum is a square adufe, like in the Golden Haggada — this one has a thick brown border, and what appear to be four fleurs-de-lis in green, with clusters of dots between them, around a central circle. Is this henna? Or paint? Perhaps the green is supposed to represent the henna paste still on the drum.

Kaufmann Haggada, Catalonia, ca. 1370, folio 3v.

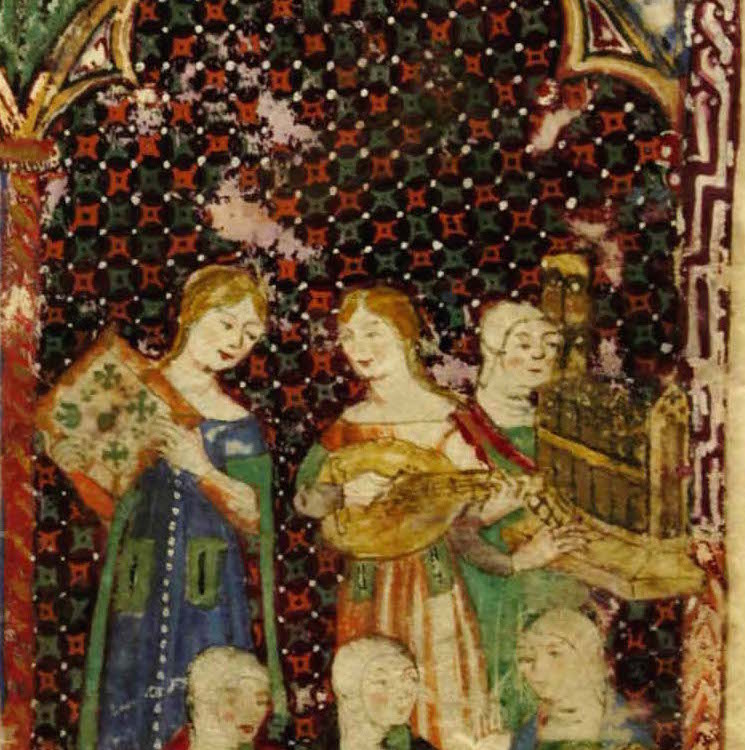

In any case, decorated drums are not limited to Jewish manuscripts! Images of frame drums appear throughout medieval Christian art as well, and as Molina has suggested, they may have Christological significance (the skin stretched and nailed to the wood) in addition to their associations with prophecy. Although many of them are plain, there are some images in Christian manuscripts that show decorated drums.

This image, from a Mozarabic Bible known as the (First) Bible of Léon, produced in 960 in Burgos (northern Spain), shows Miriam and the Israelite women playing round drums, each decorated with dark brown dots and a large circle. The perspective of the drawing is also not completely clear — the women’s hands appear to be coming out of the centre, so perhaps the inner circle is meant to represent one face of the drum and the dots the nails that attach the skin to the frame.

First Bible of Leon, Burgos, 960, folio 40v.

Interestingly, a Romanesque copy of this bible was made two centuries later (appropriately called the Second Bible of Léon), and in the parallel image it is clear that the drums are decorated — here with a X inside a large circle (on the two outer drums), and a star (on the middle drum). Unfortunately I don’t have access to a colour facsimile (if you do, let me know!) so I can’t tell you what colour the drum designs are, but it seems that the designs are lighter than the drum background — perhaps the drum was solidly hennaed and the designs scraped away?

Second Bible of Leon, ca. 1162, folio 38v.

And it’s not just manuscripts that show drum designs. A decorated drum even appears in statuary!

Two Elders is shown playing drums, one square and one round; the round drum is decorated with a six-pointed flower in the geometric proportions of what is sometimes called the Seed of Life or the Flower of Life. While it is obviously difficult to tell if this is meant to show a hennaed drum it is clearly part of the iconography of medieval Iberian decorated drums.

In conclusion: can we be sure that the decorated drums shown in medieval Iberian art were hennaed? Unfortunately, no. We are missing corroborating evidence from archaeology (actual material from hennaed drumheads) and text (descriptions of using henna to stain drumheads), and even the visual evidence itself is not entirely clear.

However, what is clear is that there was a vibrant tradition in al-Andalus among both Jews and Christians of adorning drumheads with a variety of geometric and floral patterns, including meaningful symbols, and that it is at least likely that henna was used. The possibilities for contemporary artists to reconstruct and reimagine these drum patterns, based on medieval art, are endless; as an example, here is one interpretation of the central pattern from the Golden Haggada’s drum:

Hennaed drum, Noam Sienna, 2014

Bibliography

- Cohen, Judith. “This Drum I Play”: Women and Square Frame Drums in Portugal and Spain. Ethnomusicology Forum, vol. 17, 2008.

- Doubleday, Veronica. The Frame Drum in the Middle East: Women, Musical Instruments, and Power. Ethnomusicology, vol. 43, 1999.

- Molina, Mauricio. “In Tympano Rex Noster Tympanizavit”: Frame Drums as Messianic Symbols in Medieval Spanish Representations of the Twenty-Four Elders of the Apocalypse. Music in Art, vol. 32, 2007.

- Molina, Mauricio. Frame Drums in the Medieval Iberian Peninsula. Edition Reichenberger, 2010.

Via, by Noam Sienna