How Renzo Piano’s $800 Million Cultural Center Survived the Crisis and a Decade of Delays

Despite the odds, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC), by Renzo Piano Building Workshop, became a beacon of hope amid Greece’s economic crisis and political upheaval.

Aerial view of Athens, and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, Courtesy Iwan Baan, 2016

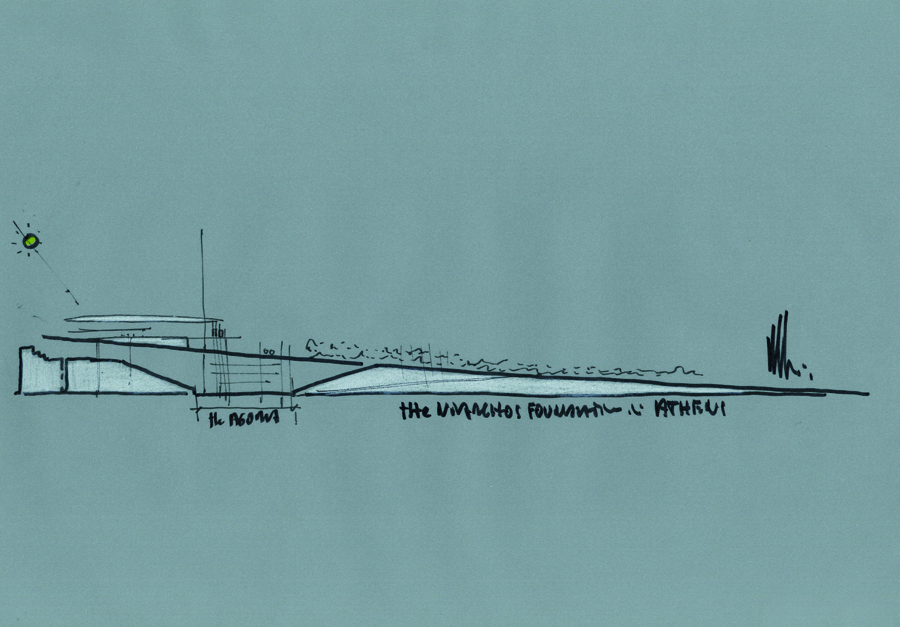

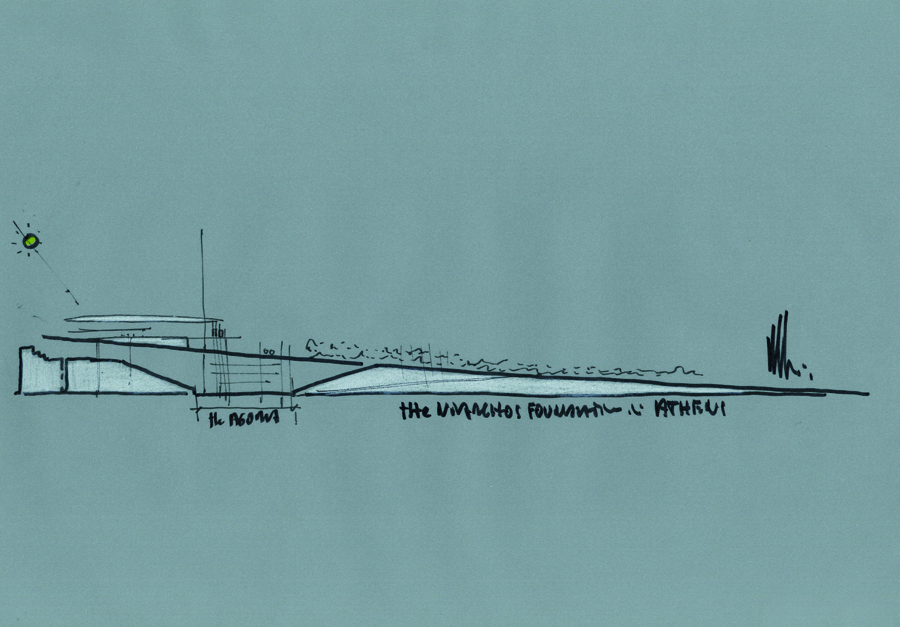

Experimentation with forms, materials, and means of sustainability has been a constant throughout Renzo Piano’s career. In Athens, for the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, he pushed the envelope of all three, and the result is two large wings of a single structure, constructed in reinforced concrete with some steel elements and separated by a sizable open-air agora — all of this embedded in a man-made hill. A huge but seemingly weightless canopy, tapered like an airplane wing, floats above this construction. Made of ferro-cement (thin-shell reinforced mortar over a layer of metal mesh and closely spaced thin steel rods), it provides support for solar panels, as well as shade, and it conspicuously signals the cultural center’s presence. A newly created park covers most of the site, climbing up the hill over the library and the garage. The center is just two miles south of the Acropolis and only a few hundred feet from the beautiful Saronic Gulf, both of which can be seen from the new building.

Investigation and collaboration on the canopy was particularly intense. In an amazing combination of old and new, hundreds of workers, usually on their hands and knees, hand-wove the connecting wire mesh of the structure’s components. The form was then filled and covered by a thin layer of sand/cement mortar. It is the most expensive element of the $824 million endeavor (the canopy cost more than $57.6 million) — the kind of effort that ends up being called visionary if successful, a folly if not.

The man who set the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC) in motion is Andreas Dracopoulos, the devoted great-nephew of the shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos, who serves as the foundation’s director, co-president, and determining decision-maker. From the moment he met the architect Renzo Piano, he was captivated by the man and by the startling originality of his concept of raising the site’s flat surface by 105 feet to create a hill as the location for the new home of the Greek National Opera and the National Library of Greece. Inspired by the mountains surrounding the capital (one of whose quarries, Penteli, supplied the marble for the Parthenon), Piano imagined a hill excavated as if for a quarry. The hilltop would provide panoramic views of the sea and the city from the SNFCC. To reconnect the city and the sea, which were separated by a four-lane highway, and to provide backup irrigation for the park, the architect envisioned a canal running parallel to the structure and extending the entire length of the site.

With the country facing such dire financial problems, embarking on an undertaking of this magnitude — the SNFCC is approximately 1.28 million square feet — defied logic. For a foundation to spend a fortune on culture in this heavily indebted country, where labor strikes were frequent even before the crisis accelerated in 2009, presented a paradox — and it was not the only one. The government’s call for a new facility for the NLG was convincing, especially because its magnificent collection of books, manuscripts, and documents was divided among three separate temporary venues; but the rationale for a luxurious new opera house was less evident. Granted, the Olympia Theater, where the GNO had performed since 1958, is woefully inadequate for opera, but the company had also occasionally appeared in the Megaron concert hall (completed in 1991), in Athens, with great success. That very success may be what encouraged construction of a new theater built specifically to present operas.

The lush Stavros Niarchos Park, which covers most of the site, will play an important role in making the cultural center a popular destination. Myron Michailidis, who in 2011 was finally appointed as the NGO’s artistic director, held his first major press conference in the park early in 2015 — an indication of the importance he attaches to this part of the cultural center.

Unlike previous models of landscape conservation, which stressed the need to protect natural resources, scenic wilderness, and rural areas from urbanization, recent approaches to landscape design have dissolved the opposition between city and nature, seeking to use parks as a means to introduce natural ecologies into urban areas. Leaving behind the Romantic idea of a park as a natural idyll that offers an escape from urban activity, most contemporary designers prefer to integrate nature and urbanism as Piano did in aligning the paths in the cultural center’s park with those of neighborhood streets.

The sketch by Renzo Piano that started it all. Already evident is the architect’s key idea– to build a hill that would lift up the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center to provide astonishing views never possible before.

The park and the other two major additions to the city of Athens were made possible by the foundation established according to the terms of Stavros Niarchos’s will. That donation is part of a long tradition in modern Greece of private support for public institutions. Niarchos began earning a living as an impecunious apprentice in the flour-milling business of his maternal uncles, and then persuaded them to expand the business by buying ships. After World War II, he founded his own shipping company and by 1956 had built it into the largest international private fleet in the world. His foundation came into being in 1996 — the year of his death — and has worked actively ever since. However, because the SNFCC was by far its most ambitious project (and its first important architecture project), the directors seriously questioned the advisability of their extravagance in December 2008, when cities throughout Greece were wracked for more than a month by violent protests. Though triggered by the killing of a 15-year-old student by the police in Athens, the demonstrations were fueled by widespread outrage and frustration, especially among young people, over the country’s growing economic difficulties.

So extreme were the problems by late 2009 that the phrase “becoming another Greece” entered the vernacular as a reference to drastic financial instability. Greece’s problems with the European Community were only just beginning their dramatic escalation in June 2011 when Piano participated in the SNFCC’s inaugural press conference. A brief disruption of the event, orchestrated by environmentalists, subsided when it became apparent that the building would introduce a new level of environmental sensitivity to Greek architecture. The only exception to generally favorable press coverage has been from the far left-wing media, which opposed allowing the SNF to use the land, criticized what it saw as tax exemptions for the foundation, and denounced what it labels private interference with government-run institutions.

Be that as it may, every mainstream newspaper in Athens carried a laudatory front-page story about the June 25, 2014, “Dance of the Cranes” that took place at the construction site in anticipation of the completion of the SNFCC’s superstructure. Fifteen hundred people, including myself, watched the sun set in the cloudless Mediterranean sky as ten giant cranes gracefully interacted in a fifteen-minute performance choreographed to the music of Gustav Holst’s suite The Planets, played by the GNO orchestra. The event replicated a similar “Dance” staged by Piano — ever the consummate showman — in Berlin in 1996, during the erection of his Daimler-Benz complex at Potsdamer Platz.

Dracopoulos, the SNF’s director, concluded the performance with a short assertion of his optimism, calling the SNFCC “an inspired project, imparting a sense of magic and a dreamlike quality to each and every one of the citizens of this country.” Piano took over the microphone to repeat his belief in the “therapeutic power of beauty.”

Dracopoulos and Piano are not the first to entertain such ideas in the face of adversity. The Empire State Building (1931) and Rockefeller Center (1930–1939) in New York City, both remarkable architectural achievements, were constructed during the height of the Great Depression that ravaged the U.S. economy for ten years. More than half a century earlier, in Paris, the Palais Garnier opera house (1875) rose during and immediately after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), in an era of turbulence even more extreme than the Greek crisis. These projects overcame the troubles of their times to become enduring masterpieces. It remains to be seen whether the Athens project will be equally lasting.

via