Beethoven wasn’t just history’s greatest composer but also one of its greatest human beings

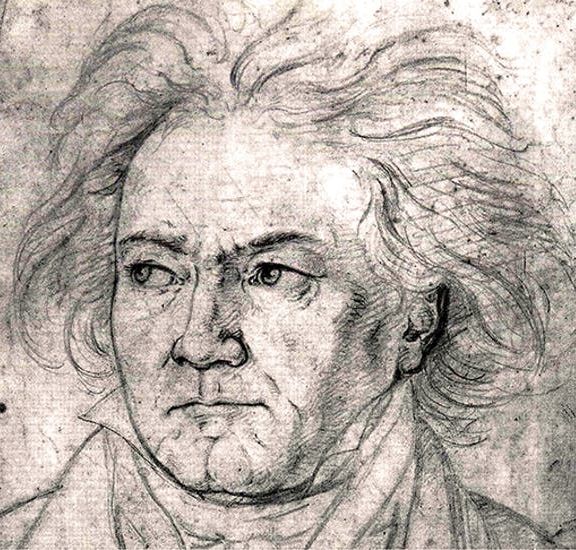

Ludwig van Beethoven (c.1818) by August von Kloeber. Image: Universal History Archive / Getty Images

His drunkenness and deafness all fed into his audacious acts of musical risk-taking

by Damian Thompson

Ludwig van Beethoven isn’t just my favourite composer: he’s my household god. There’s a bust of him on my mantelpiece. It took ages to find something that did him justice. This one was made in Italy about 100 years ago; it’s painted to look like black marble, his features are modelled on his life mask and it gets his hair right. (This mattered to Beethoven: when August von Kloeber painted him in 1818, the composer ‘expressed delight at the treatment of his hair’.) Above my stereo system there’s a Victorian copy of another portrait of Beethoven; it’s striking but undistinguished. As for the statuette in my bathroom, I should really throw it out, but consigning an image of Beethoven to a black rubbish sack seems like sacrilege — especially in the year that is the 250th anniversary of his birth, which the German government has ponderously declared to be ‘a matter of national importance’.

I’ve been a Beethoven-worshipper since I was eight years old, when my father bought our first record player. At the time we owned only one LP, given to my mother by an old flame who’d been an officer in the German army. She was also a second world war army veteran, though on our side, of course. She was nearly killed by a long-range German rocket in 1944, but she didn’t hold it against ‘Uncle Heinrich’, as we knew him, who in any case had impeccable musical judgment.

The record was Beethoven’s last piano sonata, Opus 111 in C minor, played by Wilhelm Backhaus. His style was magisterial, a touch humourless perhaps, but in the finale’s syncopated third variation he really lets rip. ‘This is like jazz!’ I told my father, illustrating the point by jiving round the room. Years later I discovered that it’s often called ‘the boogie-woogie variation’. And I once heard the manager of a record shop suggest that in these few bars, written in 1822, Beethoven literally invented jazz. ‘The slaves on the plantation could have picked it up from overhearing someone play the sonata in the big house,’ he explained.

That’s an implausible theory, to put it politely, but the variation really does sound like boogie-woogie. Even though I’ve been listening to the sonata since I was a schoolboy, I still find it astonishing. That’s Beethoven for you. You know that a particular shaft of inspiration is about to strike, but when it arrives you’re still not quite prepared for it.

It happens again and again. To quote an obvious example, there will always be something unnerving about the moment in the Ninth Symphony when a man’s voice disrupts the proceedings. ‘O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!’, sings the bass soloist: ‘O friends, not these sounds! Let us instead strike up more pleasing and joyful ones.’ But he rarely sounds joyful. It’s not just that Beethoven tugs viciously at his vocal cords, making him display almost the entire range of his voice in a few seconds. Have you noticed how nervous hecklers often sound at public meetings? The poor guy has been sitting there for nearly an hour, knowing that it’s his job to make musical history by telling the orchestra to shut up.

Here Beethoven is using shock tactics. Music critics, unimpressed by the hallowed status of the ‘Ode to Joy’, still bicker like military historians over whether the composer miscalculated. I don’t think he did, but it’s an extreme example of the risk-taking that distinguishes Beethoven from every other composer, including the only two that posterity regards as his equals, Bach and Mozart. (For what it’s worth, I think the latter matched his level of inspiration but not quite his achievement, though I wouldn’t be saying that if Beethoven, like Mozart, had died at 35.) Those risks are the essence of Beethoven; it’s barely an exaggeration to say that he takes at least one on every page he writes. To put it another way, he’s always trying to achieve something new.

Some of his gambles have an in-your-face quality: the ear-splitting dissonances in the first movement of the Eroica symphony; the invasion of the ‘Agnus Dei’ of the Missa Solemnis by the drums of war and the singers’ neurotic response; or, less noisily, the simple piano chord that opens the Fourth Piano Concerto, which in that context is almost as obtrusive as the cry of ‘O Freunde…’.

Other innovations catch the ear fleetingly or take longer to sink in. At first, we may grasp them only subliminally because Beethoven’s most profound innovations are embedded in the structure of a movement. They create shapes, patterns of thinking and atmospheres that no one else could have created. They can no more be uninvented than the atom bomb.

Can we say this of any other composer? Richard Wagner, perhaps, but his musical language is nowhere near as fluent as Beethoven’s — and in any case, Wagner was heavily in debt to him. Wagner couldn’t have begun Das Rheingold with a primeval groan if the Ninth Symphony hadn’t taught him how to create something out of nothing. And it’s hard to imagine Wagner scribbling on one of his scores ‘Utmost simplicity, please, please, please’, as Beethoven did on the ‘Agnus Dei’ of the Mass in C major.

That was Beethoven’s message to himself: to revolutionise music as economically as possible. And he succeeds, even when the page is black with notes that make terrifying technical demands. Although some of his later music may sound wild, verging on the atonal, it is not confused.

The strangeness does not reflect the chaotic despair of Beethoven’s drink-sodden personal life (he may unintentionally have drunk himself to death). On the contrary, Beethoven is making musical recompense for his behaviour. Some aspects of composing, such as counterpoint, didn’t come naturally to him. His two great fugues, the finale of the Hammerklavier sonata and the Grosse Fuge for string quartet, reach unprecedented levels of experimental complexity which still scare off some 21st-century listeners. But every note justifies itself. Beethoven sweated over them through fevers and hangovers. People in Vienna sometimes mistook him for a tramp; what they were actually witnessing was the ultimate musical perfectionist, albeit after a few too many beers.

The innumerable layers of meaning in Beethoven require increasingly powerful intellectual skills on the part of the performer as his odyssey progresses. In the Piano Sonata in A flat major, Opus 110, the fingers must let the musical argument fall to pieces in order to make way for a fragile melody that conveys what the Beethoven scholar Maynard Solomon has called ‘lament fused with prayer’.

Solomon identifies Beethoven’s greatest legacy: music that achieves a state of holiness through suffering. His ‘devotional journey’ leads us to a place of tranquillity that lies beyond the imagination of any other composer. It’s to be found especially in the only movement that reduced Beethoven himself to tears: the Cavatina of his String Quartet in B flat major, Opus 130. But he strives after it in all the significant works of his so-called Third Period, written in the decade before his death in 1827. And, despite all the fights he picked, he strove after it in his life, too. He prayed every day and, though his unshakeable belief in God was far from orthodox, he was reconciled to the Catholic church on his deathbed.

Significantly, these were the only years in Beethoven’s life in which he was almost completely deaf. When he conducted the première of the Ninth Symphony in Vienna in 1824, he carried on beating time after one of the movements had finished and was un-aware of the audience’s applause and cheers. By now he had given up hope of a cure and abandoned the fist-shaking defiance of his ‘heroic’ period. And so we are confronted with an inevitable question. Could Beethoven have created the transcendent sound-world of his last piano sonatas and string quartets if he had not lost his own hearing?

We can only guess, but instinctively I feel that the answer is no: the cruel isolation of deafness created the possibility of writing music that slipped the bonds of earth to touch the face of God. That Beethoven grasped his opportunity is an achievement almost beyond comprehension. This year we are celebrating the anniversary not just of history’s greatest composer, but also one of its greatest human beings.

My top five recordings

Piano Concerto No. 1, Mitsuko Uchida, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Simon Rattle (BPO)

The finale is the bounciest thing Beethoven ever wrote; Uchida and Rattle infuse it with special joy. A tiny unscripted flourish from the oboe in the last few bars is heart-stoppingly lovely.

Symphony No. 5, Ensemble Modern, Peter Eotvos (BMC)

A strangely thrilling Beethoven’s Fifth — strange, because tiny details spring out of what sounds like a big band. Eotvos has snuck microphones into a chamber orchestra — naughty, but a triumph.

Symphony No. 9, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Wilhelm Furtwängler (Furtwängler Sound)

The skies darken terrifyingly in this 1942 performance of the Ninth. Did Furtwängler intend to unnerve the Nazi dignitaries in the audience?

Piano Sonata No. 31, Alfred Brendel (Decca)

This live performance from 2007 represents the great pianist’s final thoughts on Beethoven’s most personal piano sonata. It unfolds naturally, with masterly command of structure and no showing off. Less is more.

String Quartet No. 15, Busch Quartet (Warner)

Beethoven’s great hymn of thanksgiving to his Creator here acquires a metaphysical longing that no other string quartet has come close to achieving. Recorded over 80 years ago and still a desert-island choice.