Forgotten Pioneer Margaret Fuller on the Singular Power of Music

By Maria Popova

“All truth is comprised in music and mathematics.”

Aldous Huxley celebrated music an expression of the “blessedness lying at the heart of things.” Philosopher Susanne Langer considered it “a laboratory for feeling and time,” whose mysterious power both eclipses and illuminates all the other arts. “Without music life would be a mistake,” Nietzsche proclaimed in 1889. A century later, music actually, literally saved Oliver Sacks’s life. In a very different way, it had once saved Beethoven’s.

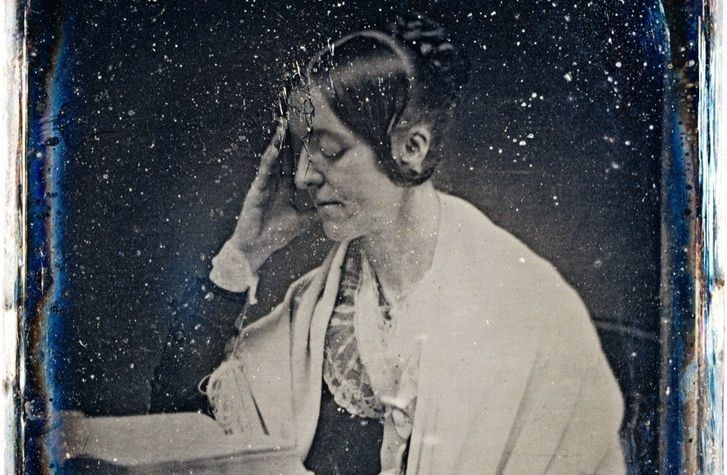

While many great writers have composed fervent raptures about the singular power of music, one of the most beautiful and penetrating comes from the forgotten pioneer Margaret Fuller(May 23, 1810–July 19, 1850) — the intellectual epicenter of Transcendentalism, who sparked the women’s emancipation movement with her epoch-making 1845 book Woman in the Nineteenth Century and whom Emerson considered his greatest influence.

On the pages of the Transcendentalist magazine The Dial and the influential New-York Tribune, where she served as America’s first female editor of a major publication and the only woman in the paper’s newsroom, Fuller wrote about art, literature, and music in symphonic essays that opened innumerable hearts to the potency of the arts as a force of cultural change and shaped the sensibility of generations.

Many of these essays were later collected in Fuller’s 1846 book Papers on Literature and Art (public library | public domain), which the young Walt Whitman devoured, recommending it heartily on the pages of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and tearing out one of the essays to save among his most precious papers.

In one essay, titled “Lives of the Great Composers,” Fuller extols the supremacy of music over all other languages of aesthetic and intellectual expression:

“The thought of the law that supersedes all thoughts, which pierces us the moment we have gone far in any department of knowledge or creative genius, seizes and lifts us from the ground in music… What the other arts indicate and philosophy infers, this all-enfolding language declares… All truth is comprised in music and mathematics.”

Decades ahead of Whitman’s assertion that music is the profoundest expression of nature, Fuller argues that it gives shape, gives voice, gives life to the richest dimensions of existence and the most inarticulable splendors of the human experience:

“We meet our friend in a melody as in a glance of the eye, far beyond where words have strength to climb; we explain by the corresponding tone in an instrument that trait in our admired picture, for which no sufficiently subtle analogy had yet been found. Botany had never touched our true knowledge of our favourite flower, but a symphony displays the same attitude and hues; the philosophic historian had failed to explain the motive of our favourite hero, but every bugle calls and every trumpet proclaims him… Music, by the ready medium, the stimulus and the upbearing elasticity it offers for the inspirations of thought, alone seems to present a living form rather than a dead monument to the desires of Genius.”

Complement this particular fragment of Fuller’s abidingly insightful Papers on Literature and Art with Kafka on the power of music and German philosopher Josef Pieper on the hidden source of that power, then revisit Fuller on reaping wonder from the mundane and her masterwork of constructive criticism that catalyzed the career of the young Thoreau.